1975 was a weird year for music. With the 70s at full steam, a cultural shift seemed to be in order as roots rock started losing ground, AOR rose in tame enthusiasm, and funk was still to properly conquer mainstream audiences. All this made it feel like a somewhat abstract time of insane highs and shameful lows, an unidentifiable vortex where anything and everything could either be highly praised or immediately dismissed as garbage — often with no in-between. An identity crisis seemingly stabbed pop through and through, while a considerable part of the music-making generation responsible for the euphoria of the previous decade just sat there, cynical and tired, bathing in a self-imposed early retirement and masticating on self-pity whilst reflecting on things past as if they’d happened 50 years ago.

Cultural transitions are never easy, and even though it seemed like the music scene was in a period of relative idleness, it was not the case for all. Neil Young was keeping up with his personal programme and riding a prolific wave of both studio and live releases as his Saturn return approached, eager to clean house and shake up a thing or two as it often does. One of these was his marriage to Carrie Snodgress, which, by the time Homegrown sessions kicked off, was rapidly deteriorating and would eventually result in separation. So it’s easy to understand how personal everything had become, how much Young had projected this difficult period of his life onto the recording process – consciously or not. It’s also clear why he’d want to abort the album’s release: “it’s the sad side of a love affair,” he now explains. “The damage done. The heartache. I just couldn’t listen to it. I wanted to move on. So I kept it to myself, hidden away in the vault, on the shelf, in the back of my mind… but I should have shared it.”

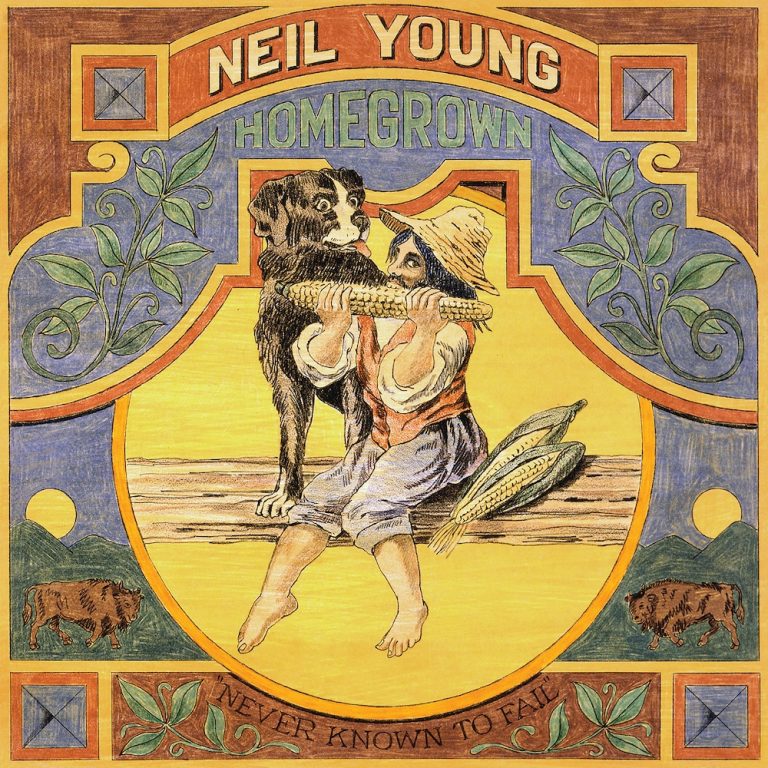

It was a last-minute decision to release Tonight’s The Night instead of Homegrown at the time, leaving this as the “mysterious, lost album” that many a Neil Young fan has chased through the decades. It has now become “the one that got away” – which, in spite of overtly being a construction made in hindsight, does contribute to its mythification, and perhaps more so now that it emerges as the limpid snapshot of a specific time and place, as if it had been miraculously preserved under a bell jar.

“Separate Ways” is a sweet beginning, reminiscent of “Out On The Weekend” with a slightly more bitter détour, which immediately reminds us that Homegrown should have followed Harvest. Emmylou Harris’ haunting voice in the background of “Try” sounds simultaneously evocative and familiar — a trait resulting from her frequent collaborations with the likes of Linda Ronstadt, Gram Parsons, and Bob Dylan.

Also fairly noticeable are members of The Band adding their two cents to the mix; Levon Helm’s trademark drumming on the first two tracks and Robbie Robertson’s guitar on “White Lines” coming across as immediately recognisable for fans of the related family.

The piano in “Mexico” seems to come straight from “After the Gold Rush”, and “Vacancy” exists in a timelapse made of “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere” and contemporary Young, sounding as fresh as if it’d been recorded yesterday. This is also true of the stripped-down “Little Wing”, which we became familiar with in a different form via Young’s 1980 album Hawks & Doves. Another throwback is “Star of Bethlehem”, again featuring Harris and closing the album like a wicked lullaby: “All your dreams and your lovers won’t protect you,” Young sings in serene disappointment, moving up and moving on with every chord.

We’re all digesting Homegrown as a piece of a puzzle we thought was so lost that we eventually accepted the hole as part of the final result, so it comes as no surprise that our first instinct is to attempt to integrate it in its rightful temporal place. This is, of course, as impossible as crystallising a collective experience — and may even prove dangerous, since our selective memory tends to look back with a tenderness that serves nothing but artificial nostalgia.

So it is perhaps best to enjoy Homegrown without this complicated exercise, accepting its delayed release as part of the album itself, and the fact that all music reaches you exactly at the time it should — usually when you most need it. As Neil Young straightforwardly puts it so himself: “Sometimes life hurts. You know what I mean.”