James Jackson Toth is an astonishingly prolific artist. At last “unofficial” count, under his various musical monikers, he has in circulation upwards of 100 releases in various shapes and sizes and formats. So it should come as no surprise to his fans that he starts out this year with yet another record under his Wooden Wand alias. Last seen sharing an album with the Briarwood Virgins back in 2011 on the underrated Briarwood, Toth has once again paired up with the Alabama super-group—consisting of members of Through The Sparks, Plate Six, Delicate Cutters, and Verbena—to craft a follow-up that he has described as “Sunday morning’s wake and bake” to “Briarwood’s Saturday night revelry.”

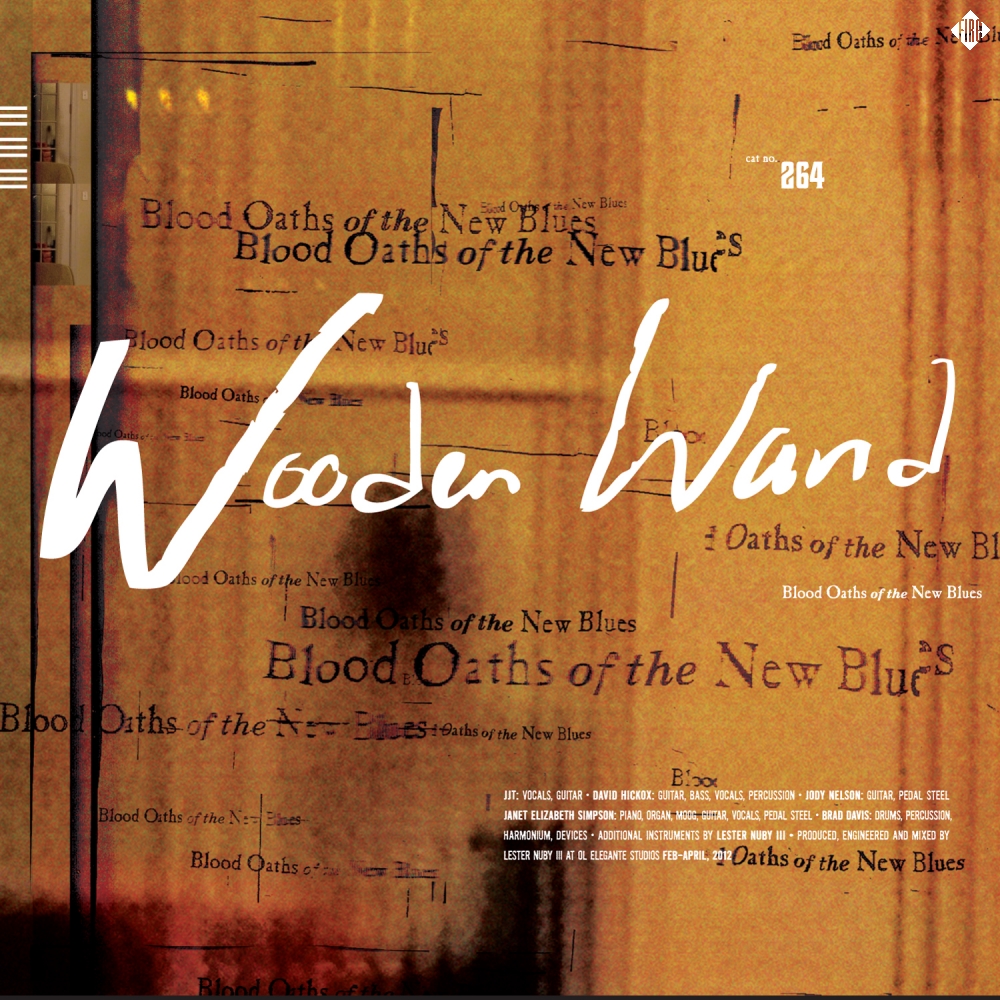

In the past, Toth and his Wooden Wand recordings have been lumped in with artists like Devendra Banhart and Akron/Family as a part of the early ’00s New Weird America folk movement, and with good reason. Utilizing bits and pieces of jazz, acid folk, and country, Toth carved out his own unique vision of what folk music might be. For him, it could be all-inclusive. And with no shortage of musical friends along for the ride, he and other like-minded musicians were only limited by the amount of musical ephemera they could pack into a single track. But in the past few years, many musicians so closely tied to that particular movement have all but disappeared, and those still around have drifted slowly away from those jazz-improv inspired sounds and adopted a more structured means of musical expression. And to a certain degree, Toth is among those that have but he hasn’t fully forgotten his roots, and his latest release with the Briarwood Virgins, the solemnly titled Blood Oaths for the New Blues, is a testament to his abilities to merge the varying aspects of his musical personalities into a cohesive aural statement.

Beginning with the 11+ minute long “No Bed for Beatle Wand/Days This Long,” Blood Oaths quickly establishes a very particular set of guidelines for the rest of the album. Much in the same way that Ocean Roar by Mount Eerie paired longer songs with some shorter interstitials, this album effortlessly swings between mammoth rural landscapes and intimate acoustic monologues at a moment’s notice. And just like Ocean Roar, these shorter songs act as a kind of harmonic glue that holds the longer tracks together with some semblance of thematic structure. Toth’s long-winded drawl pairs nicely with the shuffling Low-like beat that sustains this opening song through much of its length. Seeming to channel bands like The For Carnation and Red House Painters in equal measure, the spacious feel of this song creates an inviting atmosphere for the rest of the album to play in. But instead of a reprieve of sorts from that first track, we get “Outsider Blues,” another beautifully slow burning song that maintains the fiercely communal feel of “No Bed for Beatle Wand/Days This Long.” Bittersweet guitars mix with a rustic aesthetic and a sweetly sung melody that imbues the whole affair with a certain haunted feeling—a sense of troubled pasts and reckless decisions paid to desperate ends. And Toth makes the desperation sound so unnervingly casual.

“Dome Community People (Are Good People)” seems to reverberate with dissonant guitar tones, churning drums, and a steam-charged momentum that appears to hit its groove just as it comes to an end. Feeling very much like the cathartic epilogue to “Outsider Blues,” this short instrumental works best as a bridging piece between its bookended tracks. And I would be more predisposed to critique its lack of development but within the sequence of the tracks here, it works—but just. Another relatively shorter track “Dungeon of Irons” fares much better, with its humble acoustic beginnings spreading out to become a horn-driven parade of saws and thumping percussion.

I could comment on how some of the tracks in the second half might have benefited from more sonic variation and less dependence on the tried-and-true aesthetics so commonly found when talking about this kind of pastoral campfire music. But Toth creates such an inviting atmosphere, even when the narrative is less than perfect, that even though these small things are noticeable, they are ultimately easy to forgive. Would I have liked to have seen a bit more musical distinction in the midsection of “Jhonn Balance” or an extension of the rustic simplicity on album closer “No Debts”? Sure, but the shared sense of life lived on display here more than makes up for these slight shortcomings. Blood Oaths of the New Blues is not perfect. But it doesn’t need to be. The album, with all of its imperfections and warmly textured moments, feels well-worn and comfortable—despite its often acerbic lyrical habits. I can’t say much to Blood Oaths of the New Blues being part of an almost encyclopedic discography (most of which I am unfamiliar with), but if this is the kind of album that Toth can make after 100+ releases, then I say let the man have another 100.