“I had this idea that—I’m not a religious person, but I do believe that there’s a spirituality to a lot of people and they’re not religious. You don’t have to be religious to be a spiritual person, right?”

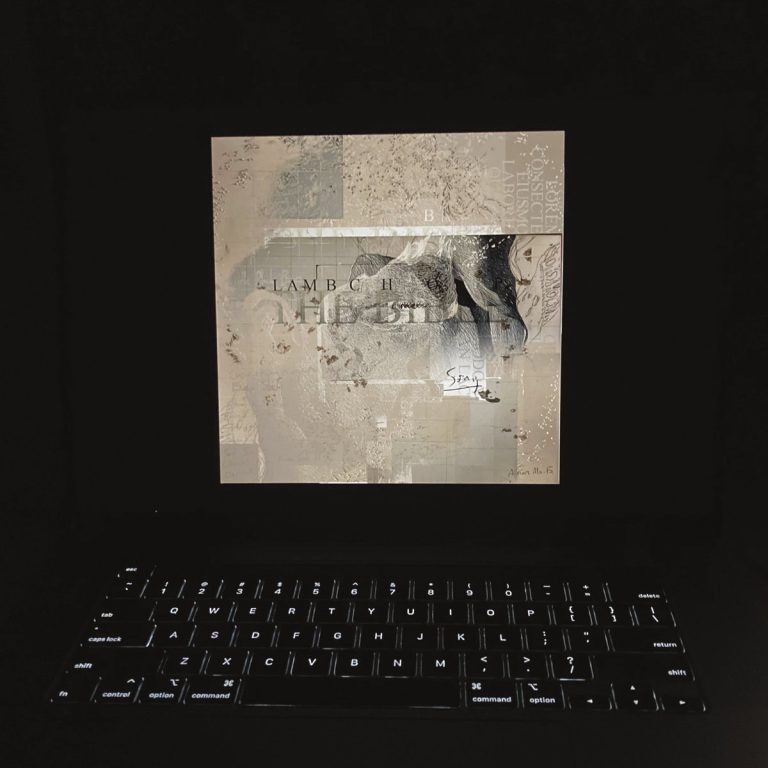

Spoken by Lambchop frontman Kurt Wagner, those words provide insight into the themes that compose the complex narrative of their latest album, The Bible, a sprawling and intimate ode to death, choice, consequence, and belief structure reconciliation. And it’s all bound up in a sound lifted from half a dozen different genres. But this album possesses a different gravity than earlier ones – maybe it’s because so much of it was influenced by Wagner’s experiences dealing with his father’s various health issues (COVID, stroke, hip replacement), or it could be that after three decades as a musician he was concerned that he no longer had anything of value to say. It deals with the impending pressure of mortality and legacy and why these things weigh so heavily on our chests.

The initial inspiration for The Bible came in the form of late-night Instagram Live performances from Minneapolis musician Andrew Broder, a friend first met through Justin Vernon in a Berlin studio just a few years ago. Wagner caught a few of these midnight shows and began to see the potential of the restless creativity Broder expressed through his piano playing. Wagner contacted him and invited Broder to mess around in a studio for a few hours, and the resulting compositions, a collection of twelve 20-minute pieces, set the tone for what would become Lambchop’s 16th studio album. Broder also produced the album (alongside Ryan Olson), the first time someone outside the band handled that particular responsibility.

Recorded in a decommissioned paint factory in Minneapolis, a long way from Wagner’s Nashville stomping grounds, the process reminded him of what it felt like all those years ago to just get together with a bunch of people without set roles and to let the music evolve as it was being played. Recalling the freewheeling disorder of the first few Lambchop releases, The Bible stands as one of their most musically unpredictable albums, an openhearted gesture of musical catharsis that gathers tones and rhythms and experimental forms from the hollows of their collective influences.

“His Song is Sung” opens the album with an extended overture of strings and piano before Wagner’s voice appears out of nowhere, a slender and occasionally frail thing that shivers in the night air. Some slight voice manipulation can be heard, a metallic echo that suggests the consciousness of some emergent mechanical intelligence. And then the horns come in, assuming a scattered and triumphant form that acts as connective tissue to the emotional ravines we’re about to explore. It’s all here, condensed (or maybe not so condensed) into a five and half minute song that acts as a statement of intent for the album and all its miasmic viewpoints.

But honestly, most of these songs could be seen as such – each is wild and prone to sudden rhythmic shudders and lyrical insight. They veer between genres with a haphazard grace, just look at the R&B/disco of “Little Black Book”, a track that warps Wagner’s voice until it sounds as though it’s just a liquid flowing through your speakers. Exuberant beats collide with Daft Punk-esque electronic melodies, creating an odd and oddly alluring brew of synthetic jazz-pop. He experiments with Baroque pop minimalism on “Daisy,” while “Whatever, Mortal” is a horn-filled gospel-tinged sing-along that flirts with Mexicali rhythms.

The steel guitar and piano on “Dylan at the Mousetrap” complement one another perfectly, giving rise to some of the most classically beautiful moments on the album. He continues to pull apart certain pop classicisms on “A Major Minor Drag”, his robotic intonations heightening a series of calmly drawn-out observations: “Something about this place / Something supple / Something warm / I can feel your hand / It stretches out to you” and “I hear it’s almost late summer in New York / And I imagine / I’m, I’m eating pizza with a fork.” These lines explore feelings that cannot ultimately be properly expressed, as well those that can be traced back to specific memories. “Every Child Begins the World Again” speaks of breaking “into Hank Williams’ casket” and moments “where I was better, not so sad as foolish”, moments when our actions were laid out before us, before we knew which steps led to heartache or joy. Guided by sparkling piano notes and scattered percussive flourishes, the song feels as though a strong wind might cause a complete collapse.

They’ve always played around with cross-stitching genres together, whether it was pilfering from countrypolitan singers, R&B, old-school funk, various folk lineages, or veins of wobbly electronic music. But they did so with a panache that few bands could match, with a mischievous glimmer in their eyes as each sound was reconstructed and employed to best serve their needs. The Bible exists as a way for Wagner and crew to refine their aesthetic embezzlement, to further break down influences and discover new ways of splicing them into crooning mutations worthy of Scott Walker or Van Dyke Parks (or maybe edging closer to The Time). Nebulous and thread through with nuanced insight into specific musical histories, these songs exist outside of the band’s usual oeuvre, groovy thumps of jazz-indentured rhythms bound by no known restrictions.

Wagner has asked big questions before – no Lambchop record is complete unless themes of death, regret, and personal purpose are offered and examined – but The Bible feels weightier, more attuned to specific moments in his life, less universal and more blatantly autobiographical. He’s always drawn from experience, whether it was his or those of the people around him but rarely has his lyrics cut so incredibly close to the bone, so near to the thump of his own heart.

Throughout all this musical realignment and creative non-fiction, Wagner ultimately grapples with trying to reconcile the past with the present, striving to connect elements of his madcap youth with who he has become and who he wants to be. By creating a bridge between these personalities, he hopes to understand who he will be tomorrow, a year from now, a decade later. The Bible is undoubtably one of Lambchop’s most mature records, but it is also one of their most honest, most unguarded in its emotional and historical perspectives. While reckoning with the struggles of his dad, nostalgia for his old Nashville haunts, and lingering questions regarding his own relevance, Wagner has helped to shepherd one of Lambchop’s finest records in almost two decades.