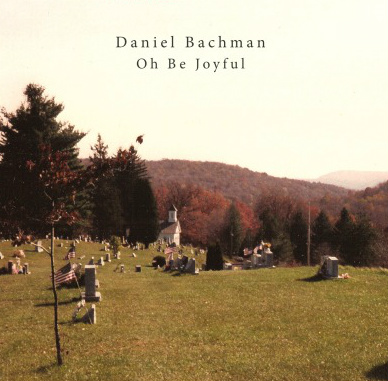

A sun rises above a graveyard. Life and loss share the horizon, in tombstones beset by mountains forest green and clothed in oak and fir.

So goes the scene on Oh Be Joyful, the second full-length from Virginia-born guitarist Daniel Bachman, not only on the art, but in the sound as well. Formerly performing as Sacred Harp, Bachman is a guitarist who has a prodigious handle on the art of fingerpicking. Every strum and pluck from him has percussive force, and each note weaves a complex sonic latticework that engages the anatomy of the guitar.

Bachman’s mannerisms evoke the memory of an aesthetic developed in the late 1950s and ’60s by John Fahey, and elaborated by friends like Leo Kottke and Robbie Basho. “American Primitive,” as the style was discernibly named, referred not only to artists of a common sound, but to a philosophy of music (“primitive” not to mean “crude,” but “unlearned”) that also formed the sound of their folk and blues predecessors.

Acknowledging the past is significant here because Oh Be Joyful is an album equivalent of a day spent in reverie. Some of the objects of reflection are more discrete (“Marfa TX,” “West 45th St”) while others appear abstract (“Sita Ram (Who is God)”). The experience was similar to what I’d imagine witnessing an elderly couple have an old photo digitally restored. What they are returned is a captured moment with surreal integrity and dreamlike perfection. With the help of Ryley Walker and Charlie Devine, the guitar is underscored with subtle embellishments, like the resounding drone that pervades the album’s opening track. Elements of a newer, psychedelic sonic palette are afforded to a timeworn sound, giving the album an ethereal quality.

The problem with this album upon multiple listenings comes when this level of retrospective romanticizing starts to seem obsessive. Nostalgia is a contentious point in modern art for a simple reason: fetishizing the past sometimes arrests progress. Those soundscapes focused on discrete subjects, like mid-album track “Rove Ryley Rove,” are saccharine, yet flat and unmoving. Those more abstract arrangements, like the last gleaming minute of “The Bridge of Flowers,” or the mantric hum that dissolves the end of 11-minute focal point “Sita Ram” pack a greater affect just from the novelty of Bachman’s own voice. It is here that his strengths as a composer begin to shine past the weighing mechanical influence of his forbears.

Bachman’s originality, in terms of instrumental style, will most likely remain a point of contention for listeners. Inheriting a style from progenitors seems contrary to the idea behind the Primitive guitarist. (From this listener’s perspective) He works best deconstructing that slender framework as it leaves little wiggling room for his imagination. Technology can be advantageous in obscuring senescence. However, its creative potential lies in its ability to create something new and imaginative.

Oh Be Joyful is a eulogy for a lost art. Bachman celebrates his idols (either knowingly or unknowingly) with immense enthusiasm, and his gift for performance undoubtedly challenges any given one. I am interested to see if Bachman’s next venture will not shine such a wistful light on the past, but celebrate the days to come.