It’s not as if Brandon Boyd one day got up and said to himself, “I’m going to make a rock album.” It’s not as if he consciously decided to capitalize on the disenfranchised masses with his assertions of caged, scripted modern life and visions of uninhibited wild freedom turned into tidy phrases marked by the standard formula of verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus.

But the suspicion is hard to shake.

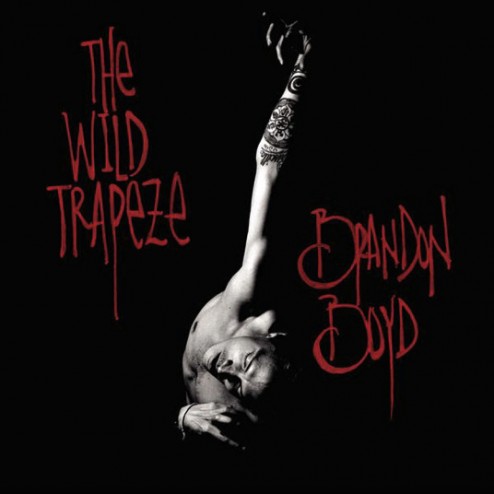

The Wild Trapeze is Boyd’s first solo venture, though it could easily have been credited to the singer’s band, Incubus, with little notice. The album expands on Incubus’ signature rock motifs with the occasional orchestral flourish and Boyd’s zen-like croon. The only difference is the artist name on the album. And Boyd plays almost every instrument you hear in the album. (“Why Don’t We Do It In The Road,” anyone?”) All in all, nothing those familiar with Incubus haven’t heard before.

The album’s themes are also nothing anyone has never heard before. The Wild Trapeze opens with the title track, a narrative about a boy on the cusp of freedom. “He’s becoming One/ The birds, the bees, The Wild Trapeze/ symbiotic heart-attack,” Boyd cries in a line exemplary of his writing style: transcendence-to-non-understanding. He’s beyond reason. He’s free! He’s free of us!

The triumphant sound of the album is checked in numerous places by meditations of “everyone/ Blunted, bleached and massed produced”; “This is our burden/ We’ve got to find another way out,” he pleads in “A Night with No Cars.” Boyd is the privileged eye, disseminating all the illusory and phony comforts of modern life. He is a high world-denier.

Consider this: The Wild Trapeze is religious music. To make a very long story short, western spirituality has inherited a long tradition of a binary in which the material and holy are apart. They are in hierarchies: holy over matter, God over garbage, angels over angles, mind over matter, mental over money. In this scheme, the material world becomes devalued because it is necessarily apart from God, Truth, Goodness, so on and so on. Now, Boyd: “Here in our gilded cage/ We turn on the news and are entertained/ We are an army of semi-informed, chemically made.” And, again: “I know I don’t belong/ There is a noise inside of me,” called soul, creative spirit, and so on. The binarism is alive and well.

Boyd frees us from ideology to freedom. “Outta your cage/ Onto your feet!” he declares at the very end. But isn’t freedom a kind of ideology? Why do I want to be free? Boyd has us lobbing grenades at the very mini-mall we drive to listening to his album. I listened to the album getting ready for work, putting on a tie, and getting comfortable in my cage. The whole experience of this album is ironic, if not a little hackneyed and typical of the artist.

Afterthought: while an album should have the same expectations as a book about morality or philosophy, some do have those overtones and are asking for the same consideration. This raises all kinds of questions about what music should and should not do. And I don’t think music should be graded on its morality. But the listener should be attentive to the ideas there. Escape and adventure are praised above all else, but what about when the adventure is done? I’m not expecting music to tell me how to govern my life (at least not so directly), but I do wonder if Boyd is taking any of his own advice by releasing a solo-album that is moderately interesting, and pot-boiler-ish for a lot of it. I love Incubus, but I think Brandon Boyd should take it easy on the philosophy and try to write music again.