All of the pieces mentioned in this article can be found on this YouTube playlist or alternatively on this Spotify playlist, for easier navigation.

Welcome to the world of classical music, where Beethoven is not a dog, Biber is not a teenage heartthrob, Alkan is not a DJ, Sibelius is not a piece of software, Humperdinck is not a sixties crooner, and fingering is not a dirty word. Classical music is everywhere – we get married to Wagner, sleep with Brahms, and die with Chopin, but few of us realise it. Classical music has never been easier to obtain, but remains an intimidating prospect for many people. The need for a little guidance, a small prod in the direction of the masterworks, has never been more essential – and hopefully, that’s what I can provide, by introducing one composer and their key works each month. I don’t want to ramble on too much this time about why you should listen to classical music, because frankly, I’ve done enough of that already. But for those of you who still aren’t convinced, here’s a little something from one of the world’s largest, and oldest, music festivals that might help change your mind. Turn your speakers all the way up, then skip to about twelve minutes in:

This month, we’re going way back, deeper into the past than we’ve ever been before, all the way back to Nineteen, sorry, Sixteen Eighty Five! Great Scott! Counterpoint Circuits on, Fugue Capacitor… Fugueing! Johann, Johann, it’s Maria … your cousin, Maria Bach! You know that new sound you’re looking for? Well listen to this! Yeah, you can probably see where this is going…

#5 – Bach to the Future

“And on the eighth day God, becoming bored, created Johann Sebastian Bach. And behold, he was very good” – Genesis, Chapter One.

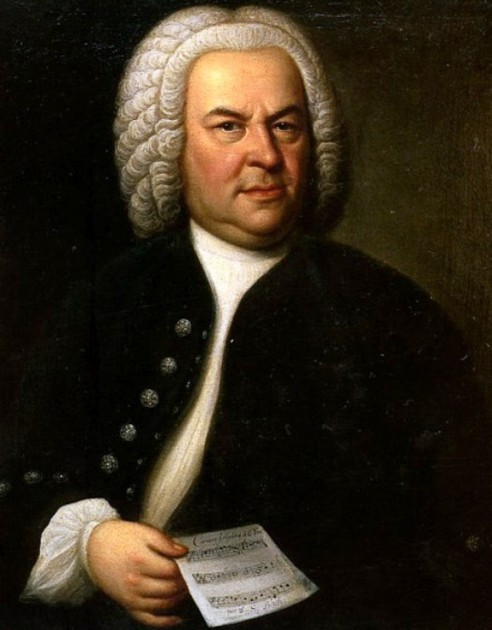

Boards of Canada had a point when they declared that Music is Math. I suspect that the likes of Autechre and Battles were more what they had in mind, but they could just as easily have been referring to Bach. I’m the sort of person who tends more towards art and history, but I know there are plenty of people out there with a very different mindset. These people are systematic, love patterns and interconnected sets of complicated rules. They tend to be good at learning languages, solving equations and playing instruments. Bach’s music was made for minds like these, and he provided an almost limitless supply of it. Calling him “prolific” is a bit like describing the universe as “fairly large” – his lifetime of diligence resulted in more than a thousand works, not counting the many pieces which have been lost or destroyed over time. While the total output of some composers could probably challenge him in terms of duration, the sheer number of notes. Bach set down is utterly astounding. His influence is pervasive, with everyone from The Beatles to Nina Simone to Busdriver (as well as other, ridiculous people) paying homage to him. His music can often seem bewilderingly intricate, arcane, dry, inaccessible, opaque, impenetrable and exhausting. In other words, it can be pretty hard-going, but don’t let that put you off, because a lot of it is still thoroughly entertaining in spite of its apparent complexity. In fact, if you listen enough the complexity becomes rewarding in itself.

I have to admit that even I wasn’t a great fan of his music until fairly recently, and I still have trouble with a lot of it. But all the pattern and rigidity begins to fall away with a little patience and careful listening. Gradually, the mathematical rigour of Bach’s work begins to unfold, revealing a world of surprising beauty and grandeur. He transformed what had once been technical exercises into brilliant new musical forms, and the endless flow of detail in his work could keep even the most fanatical listener occupied for several decades. Before we listen to the music though, we need to cover a little Bachground information. Yup, there are going to be a lot of excruciating puns in this article … but don’t blame me, Beethoven did it first.

It’s tempting to say that the closest thing to Bach in recent music is Prog, with its wilful difficulty and obsessive attention to detail, but there’s another genre which took its inspiration more directly from composers of Bach’s time. In 1964, Brian Wilson had a brainwave, and decided that it would a great idea to use a harpsichord in a pop song. Thus, Baroque Pop was born. I could cite dozens of examples of this genre which enjoyed popularity in the latter half of the sixties, but what’s of real concern to us here is the “Baroque” side of things. What exactly does “Baroque” mean in a musical context, besides complexity and ornament? Well, as it turns out, not that much.

During the Renaissance, aristocrats began collecting treasures brought back from newly discovered countries, fragments of history and oddities of the natural world, which would be placed in a Cabinet of Curiosities, the precursor to modern museums. Amongst the items displayed there were curiously misshapen pearls, which were often exploited for their unusual form and moulded into ornaments like those pictured above. These pearls were described as “barroca,” and later, during the 17th century, this term was applied as an insult to painting and sculpture which emphasised energy and dynamism instead of the calm geometry and restraint of previous generations. The musical style which came to be known as Baroque arrived quite a while after all of this occurred, so the name isn’t particularly accurate or useful, but it is convenient for describing a broad section of musical history. I won’t say too much more about Baroque style, because the music itself will make that clear, but it is worth keeping a few things in mind when listening. Firstly, composers of the time were regarded as skilled craftsmen rather than artists. They existed to serve their patrons, as well as God, so personal expression (in the sense we understand it today) was neither desirable nor necessary. Baroque music also follows a different set of aesthetic rules – balance, repetition and ornament were preferred over development and transformation. Other than that, there’s not much you really need to know.

Bach was not particularly well-known while he was alive – local performances of his work were very frequent, but few pieces were published, and his fame was limited to a small area of Germany. For decades after his death he was remembered primarily as a skilled organist and teacher, rather than as a composer, and his works were soon considered old-fashioned. Meanwhile, the two other composers born in the exact same year as Bach, Handel and Scarlatti, were celebrated for their forward-looking compositions, and his sons J.C., C.P.E., W.F. and J.C.F. Bach had become more famous for their own music. Gradually, however, composers and connoisseurs began to investigate Bach again, and his extensive use of counterpoint became a huge influence for a whole new generation of composers. Early enthusiasts included a couple of obscure musicians named Mozart and Beethoven, who both recognised and imitated Bach’s genius. But it was another few decades before Bach’s return to popularity really began in earnest, thanks to another composer – Felix Mendelssohn, who restaged some of the composer’s choral works.

Perhaps you’re wondering why I’ve been telling a series of apparently unconnected stories. Well, the fact is, we know very little about Bach as a person. We do know that he was a deeply religious man who was committed to his family, and moved successfully through a number of prominent musical positions in various German cities, but to be honest, that’s about it, and you could say very similar things about of a lot of other people who were around at the time. However, I think it’s safe to say that for Bach, music was an all-consuming passion, defining every aspect of his life, which must have been a constant frenzy of teaching, composing and playing. He was music personified, and his work is the pure, distilled, essence of music. Speaking of which, it’s about time we heard some of it…