I’ve long felt self-conscious listening to Pink Floyd’s music. Maybe it’s a generational thing, but at this point, Roger Waters, David Gilmour, and company have become so ingrained in the “psychedelic ’70s” trope that upon putting on one of their records I can’t help but wonder where I’ve been keeping my lava lamp and stash of kush. Mind you, this isn’t a slight against the band’s musical output; in fact, you could argue that during the 1970s, they practically invented the post-rock genre, and the enduring popularity of albums like Dark Side of the Moon is certainly a testament to the group’s significance and talent.

Still, they’ve never been one for subtlety, have they? From the stark imagery of The Wall to the blunt social critique on epic tracks like “Pigs (Three Different Ones),” Pink Floyd have always been quite obvious—some might say heavy-handed—about their grand messages. And it’s this obviousness, this “Dude, shit’s messed up” quality to their work, that’s hampered my enjoyment of it. Maybe it’s not a generational problem but rather a personal one, but I sometimes feel like I’m being lectured by a Sociology 101 freshman when I listen to their music, the LP-length equivalent of a Bob Marley poster and a Che Guevara t-shirt.

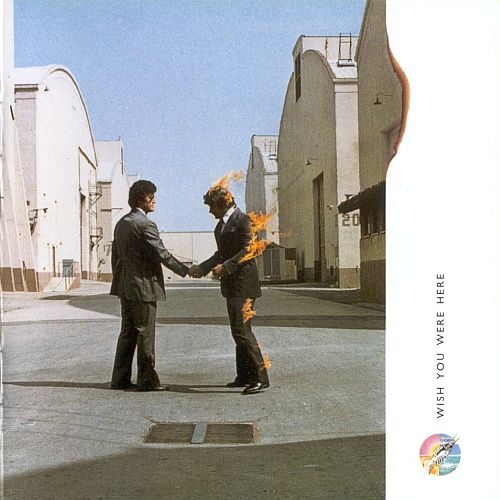

Except, that is, for Wish You Were Here. Really, this ought to be their most heavy-handed release — just look at that cover! — but it remains palpably moving, largely because it’s a work based more off personal traumas and problems than sweeping ideological concerns (e.g., “Just another brick in the wall”). Lyrically, the album is littered with real-life grievances that speak more to Pink Floyd’s status as a band and an industry juggernaut in the 1970s than to “society” or “the world.” Wish You Were Here is at once their most epic and their most personal album, which is why it’s my favorite in their discography.

Lyrically, this is an album littered with true-to-life grievances and worries. “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” is almost uncomfortably intimate, a heartfelt tribute to their one-time bandmate and friend Syd Barrett (who, perhaps not coincidentally, visited the studio while they were recording this album but had let himself go to such an extend that the other Pink members didn’t recognize him). A casualty of “the crossfire of childhood and stardom,” Syd is now a shell of a man. His eyes are “like black holes in the sky,” and his legacy has been reduced to a “target for faraway laughter.” On the album-closing second half of the composition, Roger Waters seems to whisper in Barrett’s ear personally: “We’ll bask in the shadow of yesterday’s triumph, sail on the steel breeze. Come on you boy child, you winner and loser. Come on you miner for truth and delusion, and shine.” Thus, the titular command—to “shine on”—is framed as ambiguous, either encouraging or lamenting (or, most likely, both). Does Barrett “shine” by exhibiting his skill, or does he “shine” by simply reveling in his burgeoning insanity? Waters doesn’t say—the lines I just mentioned are the last ones of the album. A lonely Moog and almost achingly tender piano carry the track to its conclusion.

As for the band’s industry success, well, don’t think they just took it in stride. We hear echoes of the music industry’s ignorance in “Have a Cigar” when acquaintance of the band Roy Harper, here tackling vocal duties after Waters strained his voice recording “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” repeats executives’ numbing lip service: “Well I’ve always had a deep respect, and I mean that most sincerely. The band is just fantastic, that is really what I think. Oh, by the way, which one’s Pink?” We can practically envision the band members squirming in their chairs while uncomfortably making smalltalk with some industry fat cat behind an imposingly wide executive’s desk. They can really hit it big “if we all pull together as a team,” which must have sounded especially hollow to the band in the wake of Barrett’s absence. They’re chugging along the gravy train all right, but where’s the handbrake? Do they even want to find it? Is this even what they really want? As David Gilmour relates being lectured on “Welcome to the Machine”:

It’s alright, we told you what to dream.

You dreamed of a big star. He played a mean guitar;

he always ate in the Steak Bar; he loved to drive in his Jaguar.

So welcome to the machine.

This is Pink Floyd’s big, dark, beautiful fantasy, culled from notes taken in the boardroom and the most honest shadows of the band members’ minds. The music itself reflects this; Wish You Were Here is sprawling, haunting, glacial, inscrutable. More blatantly synth-based than any of their previous releases, they find both superficial sheen and poignant pathos in their Moog machines. “Have a Cigar” exemplifies this: the unforgettably melancholy chord progressions of the intro, the artificial strings, the forceful guitar stabs that give an edge to the widescreen psychedelia, the hopeful-to-crushing chord changes as Harper quotes another executive: “And did we tell you the name of the game, boy? We call it riding the gravy traiiiiinnnnnnn.” On Wish You Were Here, Pink Floyd melded their songwriting ability with a dramatic but never forced epic long view; five long tracks wind their way through hooks, riffs, and even ambient noise in order to present the band’s vision.

The indisputable apex is, of course, the title track. A radio-static-drenched orchestral recording gives way to a crunchy guitar that sounds like it’s being played over the telephone. Finally, at the 1:40 mark, we get to the meat of the song: an almost suspiciously folksy acoustic guitar and revivalist piano accompany David Gilmour’s bitter alienation: “Did you trade a walk-on role in the war for a lead role in a cage?” must have seemed an especially difficult question to young American listeners still recovering from the sobering shock of the Vietnam War—some of them draft-dodgers themselves, now forced to reckon with the possibility that they made the wrong choice. A million young Syd Barretts in the face of a bleak, faceless destiny: how could their idealism help them now?

And that chorus. If ever there were a festival-ready Pink Floyd number, this is it; “How I wish, how I wish you were here,” Gilmour sings, drawling out the last word as though it were a curse. “We’re just two lost souls swimming in a fishbowl, year after year.” This is certainly not the sound of a band taking a victory lap following the commercial and critical triumph that was Dark Side of the Moon. No, they still miss Syd Barrett—achingly so—and perhaps see visions of their own destitute futures in his warped breakdown. That fear—of losing momentum, fans, friends, love—can be found all over Welcome to the Machine, but nowhere is the very human ennui that often accompanies such fears more evident than on the title track.

Which makes its transition back into “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” all the most disturbing. Back to the cold, uncaring synth tones, beautiful in their own right but perhaps representative of this all-encompassing “machine.” Back to the riffs and jams that extend past some distant horizon. Back to those electric guitars that echo like warning sirens in an English countryside. Back to the paranoia, the shame, the grotesque obsequiousness required of musical artists that want to “hit it big.” Back to all the things that make Wish You Were Here such a scary behemoth of a statement; never again would the band dig quite so deeply into themselves, returning not with answers but only blacker, more disheartening questions. “What did you dream?” It’s not that the band doesn’t know — it’s that they do know, but the answers terrifies them.