When neo-psychedelia re-emerged brightly from the ashes in the early 10s, there was already an undercurrent that had been running strong for over a decade, feeding on end-of-the-century disenchantment and niche subgenres like Paisley Underground. From this mix came style-defining releases like The Brian Jonestown Massacre’s Their Satanic Majesties’ Second Request (1996), The Flaming Lips’ The Soft Bulletin (1999), and, of course, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club‘s debut.

The somber side to an otherwise rather colorful revival, B.R.M.C. juxtaposed the remains of 60s rose-tinted nostalgia with a slightly doom-oriented pathos originating from the late 80s shoegazing in a bizarre pot-pourri that brought dirt back to rock’n’roll.

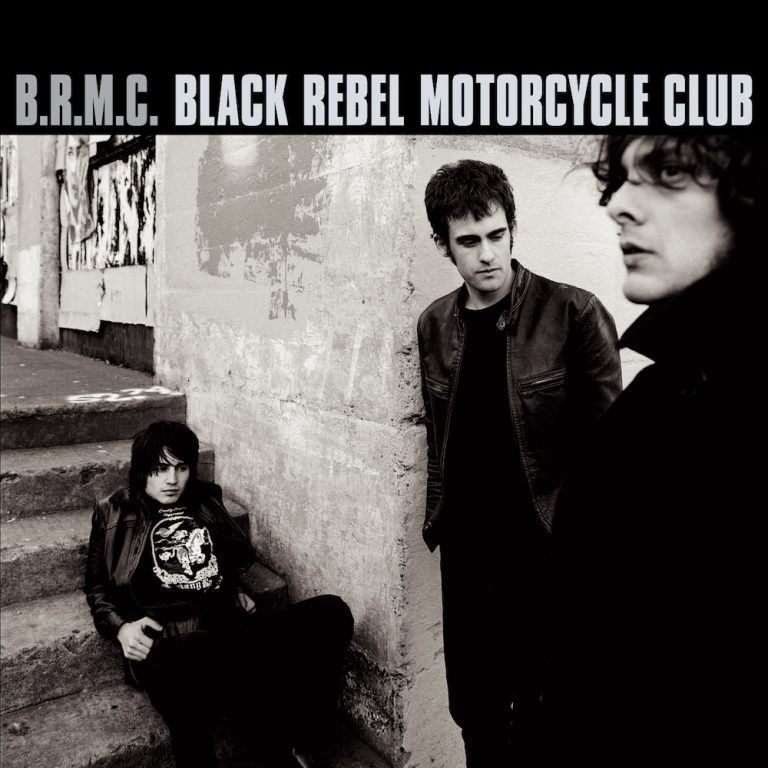

B.R.M.C. would always taste like darkness and debris anyway, since it was the result of something else coming to an end. In 1997 Peter Hayes left The Brian Jonestown Massacre shortly after the recording of Give It Back! (he’s the moody, generally quiet one in the back of the room as seen in the 2004 documentary Dig!), eventually forming his own band with high school friend Robert Levon Been. They later recruited Nick Jago, who had just moved from Britain to the Bay Area, for drumming duties — and the trinity was deemed complete.

Yet, it’s fair to say the late 90s weren’t the most auspicious times for rock’n’roll. Those transitional years between the death of grunge and the euphoria that the new millennium inexplicably brought saw the genre largely becoming démodé, with pop elbowing house in the charts while hip-hop gained momentum in a broader, increasingly international audience. After all, it all came down to how you perceived the end of the century: poptimistically or crowned in doomsday prophecy.

B.R.M.C. captured this exact moment of apparent binomial identity, offering an hour of raw and instinctive rock’n’roll that smelled of a combination of grit and freshly-cut spring blossoms. Opening with one of modern age’s most iconic three-song run in “Love Burns”, “Red Eyes And Tears”, and “Whatever Happened To My Rock’n’Roll?”, the album represented a captivating incursion into a not-so-definable era, a sort of voyage into the somber (soberer?) underworld of wilderness as religion, addiction as beatitude, and unconditional obsession as human condition.

Reception oscillated between the openly favourable and a certain skepticism, but devotees abounded nevertheless. Mark Redfern touched an important point on his review for Under The Radar, when he rhetorically asked “why settle for The Strokes when you can have this?” With Is This It following a few months later in the summer, the comparison obviously aimed at distinguishing the two routes being carved by the genre’s rather unexpected resurrection (at least in something remotely similar to its root form) at the turn of the millennium. But it also served to highlight the singularity of these newcomer energies, which were as disparate as they were animately separated. In a way, each one felt like an enthusiastic response to the other: The Strokes embodied a dizzying energy of East Coast fresh optimism in leather jacket slickness, while Black Rebel Motorcycle Club pushed towards the hypnotic fascination of the post-flower power’s demimonde.

There’s a dangerousness present in B.R.M.C. that is as tangible as an open wound, a lament that echoes throughout without ever feeling forced or even overwhelming. The urgency of tracks like “Spread Your Love (Like A Fever)” siding with the heavy density of “Rifles” or “Awake” emulates a black spark suddenly turning into a wildfire we can’t help but let idiotically burn, while the head replays that one time we jumped into something without adequately calculating the risk — only to later understand how close we looked death in the eye.

Although at its core B.R.M.C. is little more that an extension of the band’s own genesis in what instinctively feels like a psychodramatic performance of the eternal dogma of pop mythology, it still embodies what is perhaps best described as utter and genuine recklessness — that rare element rock’n’roll alchemically emerged from. Twenty years have come and passed, but every single time we put the album on it never ceases to suck us back into the vortex in mere seconds, spinning around freely and limitlessly, gloriously untamed in monochromatic ecstasy.