Listen to a Spotify playlist of our favorite tracks from BPM’s Top 50 Albums of the 2010s

10.

Big Thief – U.F.O.F.

[4AD; 2019]

When’s the last time a band leveled up like Big Thief did on U.F.O.F.? Masterpiece and Capacity (both great albums, don’t get me wrong) were carefully constructed pieces of autobiographical indie rock, at their best, totally crushing with the lightest touch (“Mary”) and spectral with the heaviest (“Masterpiece”).

But on U.F.O.F., the foursome took what was lurking underneath their best work – the desert dust of roots rock guitars and pink cotton candy cloud ambient folk – and blew it up into a 70s studio-as-the-instrument master— erhm, monument. They jam like The Band on “Cattails” and trample like Codeine on “Jenni”. Adrienne Lenker’s lyrics got a whole lot headier here too: “fragile orange wind in the garden / fragile means that I can hear her flesh / crying little rivers in her forearm / fragile is that I mourn her death.”

Even without literal interpretation, they’re scarring words, emotionally cutting just like the entire record. But sometimes, things are still clear. The last phrases on the record are “I am the photograph in you, still as the moment we’re lying in right now.” That intimacy is what makes Big Thief great. Always did and always will. – Ben Cohn

9.

Mount Eerie – A Crow Looked At Me

[P.W. Elverum & Sun; 2017]

The 2016 death of Phil Elverum’s wife, Geneviève Gosselin, deeply affected Elverum’s songwriting. On 2017’s A Crow Looked at Me, his eighth album under the Mount Eerie moniker, Elverum is eerily tenuous, as if he’s reporting from a war-torn region, the album’s atmospheres at times claustrophobically empty, at other times austerely spacious. Additionally, rather than portraying his grief through broad or abstract strokes, Elverum references everyday activities and how they are, following Gosselin’s demise, palpably defined by absence. In this way, his images, anecdotes, and musings are epically contextualized, Elverum documenting – with unadorned language and primitivistic instrumentation – his initiation into the reality of loss and impermanence.

The literary analog to Crow is Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, in which the author notes the mimetic distortions, dissociative tendencies, and transrational thinking that ensue when one has experienced cataclysmic loss, in her case her husband’s death by heart attack. Didion’s book captures the tension between her pragmatic defaults and the impact of trauma on her cognition.

Elverum too attempts to tether himself to ‘objective reality’ while he navigates the trauma of losing his wife and raising their daughter on his own. He sings at the opening of Crow: “Death is real / someone’s there and then they’re not,” voicing his resistance to the idea that one can remain bonded to the dead in some quantifiable way. On the fifth track, “Swims”, however, he reveals how he is haunted by Gosselin’s final moments and the way in which PTSS has upended his usual way of thinking: “I can’t get the image out of my head / of when I held you right there and watched you die / … your last gasping breaths, I see it again and again.”

On “Forest Fire”, Elverum sings over a melancholy strum: “I remember late August… going through your things with the fan blowing / and the sound of helicopters and the smell of smoke / from the forest fire that was growing.” He offers the listener a glimpse into the house where he is grieving, almost as if we’re voyeuristically witnessing a scene unfold on a stage. At the same time, we’re offered an aerial snapshot of the surrounding world that is increasingly ablaze, fire being referenced as an evolutionary agent and a symbol for a planet perishing from climate change. Later in the same song, when Elverum’s grief and the circumstance of the spreading conflagration are interwoven or enmeshed, he elaborates: “But when I’m kneeling in the heat throwing out your underwear / the devastation is not natural or good… / I reject nature I disagree.”

On the closing track, “Crow”, Elverum paints images of the newly defined relationship with his infant daughter. “Sweet kid, what is this world we’re giving you? – smoldering and fascist with no mother,” he sings, loosely plunked chords ringing in the background. As the song progresses, Elverum equates Gosselin’s spirit with a crow: “It was all silent except the sound of one crow / following us as we wove through the cedar grove.” The track and album close with an image of Elverum observing his child as she sleeps and hoping that the crow/Gosselin is indeed watching over them, that such a connection, despite death, might be possible. In this way, Elverum completes his aesthetically restrained yet emotionally charged, diaristic yet spellbinding, and intimate yet oddly impersonal view into the process of grief. Using A Crow Looked at Me to focus on himself and his sorrow as subjects, Elverum is transformed into a Zenic bard and an audial documentarian. – John Amen

8.

FKA Twigs – LP1

[Young; 2014]

“I love another/And thus I hate myself,” brilliantly lances open the volatile and glacially romantic world of FKA Twigs‘ debut album LP1. A spiky mire that deeply punctures the conventions and expectations of what alternative R&B could achieve, Twigs created an album that felt so paradoxically alien and human that the project simply hasn’t aged since release. Brimming with tension, ominous sexuality and bare-faced anger, Twigs explored love at its darkest and most sacrificial, clawing out experimental soundscapes with a confounding and satisfying array of producers including Arca, Paul Epworth and Joel Compass.

Twigs’ voice in its delicacy, power and quivering emotion circumnavigates these shifting sonic terrains perfectly; her melodic sensibility over such complex productions is frequently astounding. Lyrically, she is nothing if not intimidatingly – and endearingly – direct.

This is a central aspect of LP1: presenting intimacy as the double-edged sword; one that can slash an irreparable chasm between people as easily as it brings them together. “If I trust you we can do it with the lights on,” she sings on the chorus. It’s far beyond the giving of one’s body – it’s about the disclosure of the demons we all face. The ultimatums are extreme and bare-faced (“Break or seize me,” for example, or “Live or leave me”), and leave no room for her love interest to be ambivalent.

“Two Weeks” is less vulnerable and more erotically assertive. With pulsating synths, thrumming drums and a modulated refrain of “Higher than a motherfucker / Dreaming of you as my lover” woven into this seductive tapestry (among several more eye-opening lyrics), the track is both self-empowerment and talking your shit in its finest form.

“Pendulum” finds her displaced in the aftermath of a break-up, consistently torn between how she was perceived by her lover and her solitary present. With autotuned harmonies and an elongated coldness in the vocals, she emotively portrays the drawback of romance – how it almost inevitably can swing the other way. It is Twigs at her oddest, implacable and saddest.

Many years have passed since the album’s release, yet LP1 has remained one of the most engaging debuts of the decade, and announced FKA Twigs as someone at the forefront music. For all its shifting, distortion and opacity, listeners can still clearly hear the aching heart beneath these tracks. It’s not gimmicky, it’s not pretentious and it’s certainly not overrated. It’s an album that purely marries the unnatural and natural to achieve a devastating and unforgettable effect. – JT Early

7.

Joanna Newsom – Have One On Me

[Drag City; 2010]

After Ys, Joanna Newsom faced a sort of crossroads, even if she wasn’t aware of it. That album, her luminous 2006 collaboration with Van Dyke Parks, was such a monumental piece of work, full of knotty storytelling, imaginative orchestrations, and terribly impressive song lengths. It was unlikely she’d be able to ‘top it’ in any traditional sense, and surely she did not want to repeat herself.

And so we were given, after a four year wait, her third record, Have One On Me. At first, it almost seemed like a subtle joke – with Ys being five songs and about 55 minutes long, Have One On Me is almost like Newsom saying, “Ha! You thought that was long?” The album tops out at just over two hours, and stretches across 18 tracks on a 3xLP. It’s heady, dense, complex, layered, rich; the longest song is 12 minutes, and several others pass the seven minute mark. But hardly a single second is wasted; the album coalesces its many moving parts into a gorgeous document of love gained, loneliness grown, and love lost. If one wanted to find it, a storyline can be roughly divided from the songs on this album, lending it the air of a concept album without getting too caught up in the trappings of such a thing.

The first disc has mostly the more happy or upbeat songs, and also provides a good inkling as to where we’ll be going over the next two hours. Harps and pianos (played expertly by the profoundly dextrous Newsom) are met with horns, guitars, woodwinds, inventive percussion, and a slew of other odds-and-ends instruments that one might usually find in a European folk band, or a renaissance faire, such as tambura, mandolin, or kora. It’s an evocative soundscape that also borrows from 70s folk pop and rock; there are even strains of jazz and blues in some of the melodic choices and vocal inflections. “Easy” has a bluesy sway to it, and “Good Intentions Paving Company” has a bouncy rhythm backing sweet lyrics like “I just want for you to pull over and hold me / Til I can’t remember my own name.”

But then the first disc closes with the tragic “Baby Birch”, and all starts to go south. On the second part, we start to see loneliness and distance creep in. The amazing “Go Long” uses the myth of Bluebeard to tell a tale of a woman whose lover leaves her far too often, to the point where she starts to wonder about their relationship, or if any secret tensions lie unresolved. “In California” has the woman essentially asking someone (it’s unclear if it’s the same lover who has gone away) that they come be with her, but it might disrupt the balance. Closing with the spartan piano number “Occident”, the woman seems perhaps at peace with what’s been going on, and starts to try to settle on a conclusion.

That conclusion comes on part three, namely in the finale, “Does Not Suffice”, which is surely one of the most tender, mature, and deeply sad breakup songs of the last 20 years, if not even longer. Using the same melody as a central part of “In California” (deepening the ties and links across the album, of which there are bound to be many as yet undiscovered), Newsom details the sorrowful end to the relationship. She even references the very first track — “Easy” begins with Newsom describing all the ways she is “easy to keep” and how she “intends to love” this person — but now, two hours later, she is taking away all the things that remind the lover “how easy I was not.” When she gets to album’s final, staggering verse —

The tap of hangers, swaying in the closet

Unburdened hooks, and empty drawers

And everywhere I tried to love you

Is yours again

And only yours

— it’s truly heartbreaking.

Have One On Me may be long, but it also justifies its length. You also don’t necessarily need to hear the whole thing at once every time – the three discs split off into their own neat albums, more or less. But taken as a whole, it’s astonishing. No one writes songs quite like Joanna Newsom. Her voice is unique, yes, but so is her lyrical style. Her words are so full of poetry, so moving in their intimate details of life and philosophy and allusion, her imagery so tactile and inventive. Almost no song here has a decided chorus, and yet they rarely feel ambling.

With such a bounty of beauty, texture, wit, and care on display from Newsom and all her collaborators (including multi-instrumentalist and composer Ryan Francesconi), Have One On Me is a varied, engaging, and awesome document of American music. – Jeremy J. Fisette

6.

David Bowie – Blackstar

[ISO/Columbia; 2016]

David Bowie is one of the select few artists in history who never suffered from his music not sounding fresh. It was something that remained true right up to his final, inspired work.

Blackstar is shrouded in even more mystery due to Bowie passing away a mere two days following its release, before listeners were able to properly process it. Some call it swan song, or his “parting gift to the fans” as his long-time collaborator Tony Visconti suggested.

Never one to take the straight path, Blackstar is not a warm goodbye, but an unsettling masterpiece that is not interested in giving the listener closure. It instils a sense of his everlasting presence, but it’s one that is ominous more than comforting. This is reflected in the music videos for the title track and “Lazarus”, which are blood chilling as well as they are hopeful; neither of these feelings could be properly put into words, they are such unconscious emotions that language cannot convey their substance.

Blackstar is not a record that is straightforwardly transformative. It takes its time, lingering in the back of your head, until you find yourself inexplicably drawn to this album. Each new listen may yield a new discovery, and this cycle will go on. – Aleksandr Smirnov

5.

Frank Ocean – Blonde

[Boys Don’t Cry; 2016]

Just as it is argued that modern human history can be separated between pre- and post- the atom bomb, the age of modern music can be divided between pre- and post- Blonde. It’s always an unprecedented moment when Frank Ocean releases music, and on Aug. 20, 2016, he righteously swindled label conglomerate Def Jam to gift us something that was nothing short of momentous.

Ignore, for a moment, that Frank is one of the more beguiling artists of our generation. In all of its complexities, Blonde was cherished and revered because it celebrates the identity of the depressive misfit living in a gradually frigid digital world, which appealed to that odd intersection of shared experiences between younger Millennials and older Gen Zs A group of individuals who will forever exist within history as the second lost generation — inadvertently directionless, hopeless, but nevertheless, conscious of the corrupt world around them, these were the very listeners that connected with Frank as he traversed the grey areas of life with vivid emotion and clairvoyant insight.

After Channel Orange, Frank didn’t necessarily do away with his cohesive R&B-encased confessionals, but he did further mystify his vision with exploratory sounds and sentiments. This album’s frigid mystery rendered Frank’s life story even more compelling, allowing listeners a rare opportunity to invest and care deeply about their pre-ordained savior of millennial malaise. Blonde defied what it meant to vibe and cry all at once.

Though many didn’t recognize it at the time of its release, Blonde wasn’t just a vessel for Frank to ponder the complexities of his own identity, sorrows, and anxieties. It was a record that ripped open the seams of pop music so that others within the mainstream could also color outside of lines. Without this project, we don’t get Tyler, the Creator’s recent alt turn;, we wouldn’t have the Khalids and Daniel Caesars of the world, nor, if we’re going to be completely honest, would we have someone as boundary-pushing as Lil Nas X. Simply put, the popularity of genreless music begins and ends with Frank Ocean, and it’s all because he bared his soul and vision without consideration of how the mainstream would receive it. No compromises. – Kyle Kohner

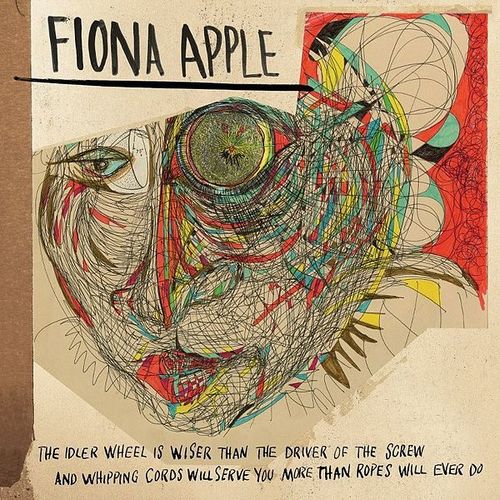

4.

Fiona Apple – The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do

[Epic; 2012]

The Idler Wheel was an unexpected masterpiece. Here, Fiona Apple is at her most fluid, but also her most restrained, balancing the bold with the brash, occasionally giving into slight indulgences.

After three albums, the machinations of Apple’s music would no longer do her justice. She’d evolved too much to write as conventionally as she had before. Everything Apple had done in the past was thrown away in favor of a clean slate, an obvious reaction to the turmoil experienced with Jon Brion during the Extraordinary Machine recording.

There’s a different feel to The Idler Wheel right from the start. The bluesy bellows on “Every Single Night” finds Apple at her most condensed thematically, harnessing her abilities but also erecting a mental wall to protect her doubts and fears. It’s the type of mentally stabilising song the world needs, making it the perfect accompaniment to The Handmaid’s Tale‘s depiction of revolution. That’s what Fiona Apple is, whether you want to admit it or not: a revolutionary. – Tim Sentz

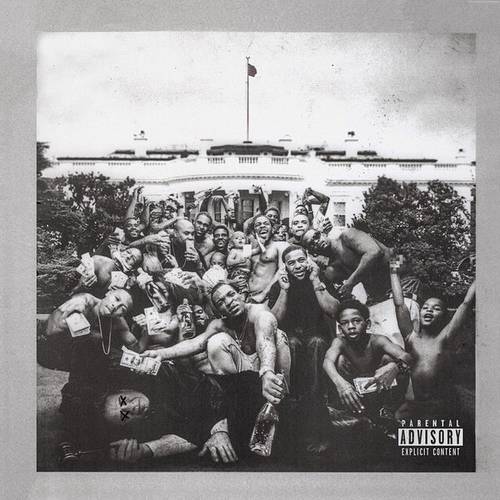

3.

Kendrick Lamar – To Pimp a Butterfly

[Aftermath/Interscope/Top Dawg Ent.; 2015]

Following 2011’s Section.80 and 2012’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, Kendrick Lamar released his masterwork, 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly, crafting some of hip-hop’s most sublime beats and uber-eloquent lyrics. Navigating palpable grief and outrage, Lamar asserted himself as a hustler, mystic, seeker, maverick, and truth-teller, as well as a musical and social historian. He tells us in “Momma”: “I know street shit, I know shit that’s conscious / I know everything I know lawyers advertisement and sponsors / I know wisdom I know bad religion I know good karma / I know everything ….”

Lamar proceeds to explore the heights and depths of vulnerability and aggression, from his optimistic proclamations on “u”, spotlighting Kamasi Washington’s textural offerings on tenor sax; to his vitriolic commentary on racism and the shadows of capitalism, as voiced in “King Kunta”, which may well include the decade’s most compelling groove; to the confrontational tone and content of “The Blacker the Berry”, inspired by the murder of Trayvon Martin.

Lamar has woven his own Iliad and Odyssey, constructing a storyline delivered cumulatively throughout the album, as if by a Greek chorus, starting with the line: “I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence.” At different points, subsequent elements are added, building on what has already been offered, including references to “resentment,” “depression,” “self-destruction,” “the evils of Lucy” (specifically Lucifer, generally the perils and snares of success), “survivor’s guilt,” and “the wars of apartheid and discrimination.” In this way, Lamar creates a framework, an archetypal quest-and-return that culminates with a call to unity: “Made me wanna go back to the city and tell the homies what I learned.”

The final track, “Mortal Man,” shows Lamar contemplating Black history and his role in it, meditating on the gifts and challenges of fame and wealth. While these reflections reaffirm Lamar’s persona as the underdog who has overcome social, economic, and existential adversities to emerge as hero and antihero, “Mortal Man” is characterized by sincere inquiry and unabashed revelation that exceed predictable hip-hop tropes: “Do you believe in me? Are you deceiving me? / … Is your smile on permanent? Is your vow on lifetime? / … If the government want me dead plant cocaine in my car / would you judge me a drug-head or see me as K. Lamar?”

At the end of the track, Lamar samples Mats Nileskär’s 1994 interview with Tupac Shakur and splices his own questions into the dialogue, staging a makeshift conversation with one of his mentors. Near the conclusion of this exchange, Lamar asks Tupac to respond to a poem he (Lamar) has just shared. Tupac is palpably absent. Lamar repeats, “Pac? Pac?” to no answer, the silence marking the end of the track and album. This haunting truncation creates a memorable and even traumatic rupture, evoking Tupac’s death and the universality of loss. In addition, Lamar is self-prompted, as possible spokesman for a new generation of artists and Black men, to find and trust his own sense of direction – in music and life.

It’s worth mentioning that To Pimp a Butterfly, as well as being ambitiously complex and hyper-elegant in its structure and content, is flat-out entertaining to listen to, replete with unshakeable rhythmic, lyrical, and vocal hooks. Provocative art is often most successful when it assumes a palatable form, appealing to pop expectations while concurrently transcending them. This is the case with To Pimp a Butterfly: we’re mesmerized by its immediacy, profoundly altered by its sophistication. – John Amen

2.

Deerhunter – Halcyon Digest

[4AD; 2010]

Our memories make us cry, ache, smile, feel alive. Perhaps nobody has understood the complexities of memories better than Bradford Cox. He knows they aren’t recordings but ever-changing distortions that inevitably shape who we are. Yet, these distortions are our own creation, and what a creation is Deerhunter’s fifth album Halcyon Digest.

Produced by Ben Allen, the album retains a distinct sonic palette that beautifully, hauntingly, reflects its lyrical themes. These 11 songs swirl, rumble, pulse, and echo: opener “Earthquake” does all four while Cox’s dreamlike voice asks us again and again “Do you recall?” Rarely does an album brim with such life.

Yet life isn’t always a joy; on the hushed “Sailing”, Cox details the feelings that come with isolation. “Only fear / Can make you feel lonely out here”, he sings, followed by the unsettling admission “You learn to accept / Whatever you can get.” Perhaps that’s true, but the following track “Memory Boy” suggests the fear lies in the memories that creep in while you’re alone. “Did you stick with me? / Let me jog my memory” Cox sings over glossy guitars and a persistent drum cadence. “Try to recognize your son / In your eyes he’s gone, gone, gone, gone, gone.” Here, the victim isn’t the father but the son and his accompanying guilt for whatever took place.

Loneliness and the queer experience tragically go hand-in-hand, and this truth is handled most explicitly on the kaleidoscopic masterpiece “Helicopter”, a song about Dmitry “Dima” Makarov, who was a victim of human sex trafficking. Lines like “I have minimal needs / And now they are through with me” are soul-crushing: why do these things happen to people? Yet the album is also imbued with hope; the lo-fi-esque “Don’t Cry” has Cox comforting a boy, reminding him “And I understand / The pain you’re in” over gritty guitar strumming. Moments like these remind us that memories are among the intimate things we can share, that they can be used to extend true empathy.

Album centrepiece “Desire Lines’ is among the band’s most esteemed and beloved tracks: Lockett Pundt’s arpeggiating guitar solo and Joshua Fauver’s thumping bass on the song’s outro could roll on forever.

Halcyon Digest concludes with the pensive “He Would Have Laughed”, a tribute to Jay Reatard who died in January 2010 at the age of 29. Accompanied by Paul McPherson’s sparkling 12-string guitar, Cox meditates on the mundanity of adulthood and the shifts in priorities that come with it. “I’m a gold, gold digging man / I won’t rest ’til I buy your land,” he sings, his voice just far away enough to evoke someone who isn’t present mentally (a condition that comes with aging) or physically (the passing of Reatard). Yet, just as the song swells into its glossiest, most serene moment – it ends, just like memories flash in the mind, free of any logical conclusion.

This album is now 11 years old: how times have changed since then! Those of us who remember its release – or our present distortions of it – likely recall its critical acclaim, its regard as a masterpiece of indie rock, the immediacy that sticks beyond its 46-minute runtime. Those aspects will never change. I’m sure I speak for many of the Beats Per Minute writers when I say Halcyon Digest will always make us cry, ache, smile, feel alive. – Carlo Thomas

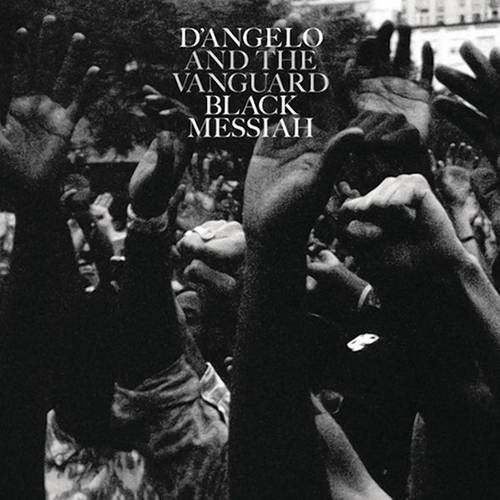

1.

D’Angelo – Black Messiah

[RCA; 2014]

If you haven’t heard Brown Sugar, listen to it right now. Seriously, stop what you’re doing and put it on. D’Angelo’s debut is his first classic, and an essential part of his story. Barely 21, D’Angelo wrote, composed, arranged, produced and performed almost everything on Brown Sugar. Understanding it as a masterpiece of a debut gives context to the kind of pressure D’Angelo has been under ever since. He followed that up with the 2000 milestone Voodoo, and then more-or-less played the background for 15 years.

So much happened after Voodoo that only D’Angelo will ever know. You can speculate about the years of apathy and addiction, but only he lived it. To a fan, it feels like that pain is carried on Black Messiah into “1000 Deaths” and “Prayer”, two of the darkest tracks D’Angelo has ever touched. As apt as comparisons to Prince and Sly Stone are (and shit, those aren’t two names you just throw around!) given D’s talent as a prodigal multi-instrumentalist, I still find Curtis Mayfield as perhaps his strongest influence. In particular, the drugged-out dirge of late-era Curtis on “Here But I’m Gone” feels reflected in “Prayer”. Heavy shit!

Outside of “The Charade”, I’m not sure if Black Messiah has the lyrical ties to the Black Lives Matter movement that it is commonly made out to have. What I do recognize is a sense of ever-relatable malaise of spirit, of wistfulness: “I just wanna go back / Back to the way it was”; “Do we really know / Do we even care?” No longer mistaken for a 20-something R&B star, D’Angelo instead comes across as a weathered soul, one who has felt the peaks and depths of human experience. This brings a potency that, in his discography, is unique to Black Messiah. Songs like “Really Love” and “Betray My Heart” seem to say, “I have loved you all these years, and my love is still true.”

Yes, amongst the pain there is also love and joy on Black Messiah. It’s the kind of love that soothes the spirit, the kind of joy that makes the future seem a little brighter. The sky opens up on the transcendent “Another Life”, every “oh!” traded back and forth at its climax in musical ecstasy. Despite the odds, Black Messiah turned out to be as timeless a classic as D’Angelo’s first two albums were. And it’s still great make-out music. – Ethan Reis

Read our Albums Of The 2010s: Honorable Mentions.