Listen to a Spotify playlist of our favorite tracks from BPM’s Top 50 Albums of the 2010s

40.

Death Grips – The Money Store

[Epic; 2012]

[Review found on abandoned Geocities flash site]

Death Grips is online! They’re on www.DEEPWEB, looking at your nudes! Offended? B!†qh pls // the 20th century is dead – 9/11 killed it! What’S left of it dwells in perverted chatrooms and dirty corners. The Mariana trench is a virtual candy shop of polymorphous paranoia, and it’s filled with links to half deteriorated mp3s and algaerhythms.

In those cryogenetic depths, MC Ride shouts his unholy verses, which Zach Hill and Andy Morin reconfigure into chaos magical sigils. The sounds therein are often familiar – screeching tires, digitized voices, police sirens – but distorted and, like everything here, deeply haunted. The world bends in on itself as our subconscious desires take a definitive form.

But who is this music for? The cover imagines rare Hentai collectors that listen to the Sex Pistols. “I’ve Seen Footage” suggests teens whose iPhones brought liveleaks atrocities into their basement bed rooms. “Blackjack” conjures hellish spectres harbouring their online banking, but only “Hacker” finds a definitive image: it’s your favorite intern from WIKI>LEAKS: he’s in (HE KNOWS YOUR FIRST THREE NUMBERS). And when you come out of this album? Your shit is gone!! This might not be DG’s best album, but it’s their most loved, therefore most hated. 01001100 01100101 01110100 00100000 01110100 01101000 01100101 00100000 01100100 01100001 01110010 01101011 00100000 01100101 01101110 01110110 01100101 01101100 01101111 01110000 00100000 01111001 01101111 01110101 00001010. – John Wohlmacher

39.

Bill Callahan – Apocalypse

[Drag City; 2011]

After releasing 14 albums under the moniker Smog, Bill Callahan began releasing projects under his own name, the third of which was 2011’s Apocalypse. One of Callahan’s more thematically arced albums, the sequence opens with “Drover”, carried by an acoustic guitar and lulling melody that invoke the mid-late 1800s American-West mystique; i.e., “Home on the Range”, as well as the country’s longstanding fascination with outlaw icons. When Callahan sings, “One thing about this wild, wild country / it takes a strong, strong, it breaks a strong, strong mind,” he recalls the popularized glory of the American pioneers while alluding to the imperialism of America and American “manifest destiny,” a term coined in the 1840s. In this way, Callahan highlights how the “settling” of the West was, on one hand, a bold venture undertaken by tough-minded people ready to risk everything and, on the other hand, a ramped-up persecution of the land’s original inhabitants, which continues to this day. The end of the song transitions from a pastoral and spacious sound to a more cluttered and hectic ambien, creating a sense of urgency and evoking a palpable anxiety.

The album’s pièce de résistance “America!” expands on this theme. The song opens with a choppy rhythm, Callahan’s equanimous voice wafting atop the distorted guitars, bringing to mind Woodie Guthrie backed by a Ramones-inspired garage band. A wiry electric guitar that conjures a cross between J Mascis, Gary Clark Jr, and Steve Vai slices across the soundscape. The piece is a satire on American cultural and political norms and a commentary on the US’s hegemonic bent. “I never served my country,” Callahan says, before mentioning “Afghanistan! Vietnam! Iran! Native Americon! America!” While the electric guitar continues to buzz and saw across the soundscape, Callahan announces, “The lucky suckle teat / others chaw pig knuckle meat,” addressing the inherent inequities of capitalism. The song concludes with Callahan cleverly employing the double entendre of “Ain’t enough teat”/”ain’t enough to eat,” the song at once whimsical, trenchant, and haunting.

Having navigated six tunes that directly or indirectly examine nationalism/Americanism, pride/patriotism, the intriguing and mind-draining aspects of pop culture, and how these matters feed into broader existential challenges, Callahan finishes his set with “One Fine Morning”. The track echoes the album’s opening, a laid-back acoustic strum supporting Callahan’s voice, then a mostly melodic but occasionally discordant piano part adds tension. A distortedly ambient guitar provides a dose of urgency, as Callahan sings, “The curtain rose and burned in the morning sun.” When he proclaims, “No more drovering,” he is perhaps speaking into his own desire to settle down and loosely calling for the end of practices that led and still lead to cultural, economic, and environmental injustices (he probably wouldn’t blame the drover but rather the baron who paid him and the governments that partnered with that baron financially, logistically, and, in many cases, militaristically).

In this way, the album closes with a characteristically confessional and elusive tone, Callahan’s voice both confrontive and oddly disembodied. Apocalypse shows the singer-songwriter at the peak of his restrained eloquence, embracing a complementary and provocative sonic palette. – John Amen

38.

Sufjan Stevens – Carrie & Lowell

[Asthmatic Kitty; 2015]

No matter how many times you listen to Carrie & Lowell, at some point, you’ll always come across a devastating scene or turn of phrase that would bring the most calloused to their knees in a puddle of tears. That’s the magic of Sufjan Stevens.

In all of his career sonic explorations and ventures, Sufjan has never amazed or devastated as much as he did when he stripped everything back on his 2015 record. Though he brought his sound back down to earth following the weird and experimental Age of Adz, the minute and intimate nature of this record still allowed Sufjan to flex his world-building abilities by telling captivating stories that exude secrecy and intimacy. Sufjan’s music was always wrought with moments of soul-crushing sketches of heartbreak and melancholy. But he never went as deep into the origins of this pain until he decided to explore it fully by framing it around his mother, who battled with depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse before she died in 2012.

Sufjan could have succeeded the surprisingly experimental Age of Adz with something even more magnificently weird. But sometimes, the pain and questions that death can deal are often too heavy to bottle up, so much so that the simplicity of storytelling and sound can be all one needs to exorcise those depressive thoughts. From death and five years of silence sprouted a record alive and loud in its frigid folk sound, which cradles the stories between him and his mother. Though many of the memories he holds are far too painful to retell, he still decided to lift the obscure veil with uncomfortably personal vignettes that gave listeners a more profound appreciation for the type of storyteller Sufjan is.

Few artists can more completely remove the threshold between the intensely private and the staggeringly universal than Sufjan, and Carrie & Lowell is the epitome of his illusory, magician-like abilities. Even when combining fantastical storytelling, historical facts most wouldn’t care to know, and of course, biblical references, Sufjan demystified his own character to deliver a masterpiece that was and still is one of the most sincere and uncomfortably vulnerable records ever made. – Kyle Kohner

37.

Weyes Blood – Titanic Rising

[Sub Pop; 2019]

Natalie Mering works in the world of nostalgia. As Weyes Blood she has an astute and wistful talent for conjuring feelings of past days spent contemplating existence, or that ineffable longing a movie leaves you with once you come out from the darkness of the screen. Her fourth album, Titanic Rising, is her strongest album to date, swirling all her powers into a document exploring everything from existential dread, to everyday relationships, to the collective experience of watching romance on the big screen.

It’s Mering’s deliberate amble that is perhaps the most striking though. Every step is measured and considered, from the vowels she sings serenely to the musical accompaniments; the way “Movies” unravels from a synth arpeggio to an almost-discordant violin razzle, or the Celtic flourishes of “Everyday” are understated yet decadent moments you want to enjoy repeatedly.

Even when all the 60s/70s inflections of the music are stripped away on the titular musical interlude, Mering still has a magical way of creating a sense of weightlessness, like you’re floating amidst the wreck of the album’s titular vessel. If you can’t quite describe the feeling Titanic Rising evokes, then it’s probably just nostalgia in some form. It’s Mering doing what she does best. – Ray Finlayson

36.

Ought – More Than Any Other Day

[Constellation; 2014]

While one can easily attribute the origins of post-punk’s third iteration to the likes of Protomartyr and Savages, the post, post-punk revival began in 2014 in Montreal, Canada. The genre’s reinvigorating recall could be partly accredited to Ought and their first full-length, More Than Any Other Day.

Ought’s brand of post punk isn’t interested in capturing the obscure darkness of post-punk pillars like Joy Division and The Cure. Instead, More Than Any Other Day found itself innately in line with the genre’s angular roots of the late 70, harkening closer to Television, The Fall, and even Talking Heads. It’s frantic, fidgety, and maintains a level of complexity that bands of the second wave failed to elicit. With a few beautiful orchestral flares to boot, More Than Any Other Day, overall is a brilliant album – one deserving of recognition for the path that it laid. – Kyle Kohner

35.

Lingua Ignota – CALIGULA

[Profound Lore; 2019]

Kristin Hayter does not fuck around. This, after all, is a woman who published a dissertation of copy-pasted extreme metal lyrics called “Fuck People, Kill Yourself, Burn Everything”, whose 10,000 pages equated to her own body weight in paper. Lingua Ignota‘s uncompromising 2017 album, All Bitches Die, heralded a voice to watch out for. And yet, nothing could have prepared us for 2019’s CALIGULA.

Granted, it’s not going to be to everyone’s taste. For many, it will simply be too extreme, too discomfiting, too triggering, too confrontational. It is a harrowing portrait of emotional and physical abuse, rendered in a musical language informed by experimental noise, avant-garde modern classical, metal, opera and choral music. It takes Christian iconography and smears it with blood and tears, burns it down, then eats the ashes.

The album is so haunting and terrifying that it found its way onto end of year best metal lists, despite bearing little resemblance to anything around it. Yes, it came out on Profound Lore. Yes, Hayter black metal screams her lungs out. Yes, there are some passages that feature extremely heavy guitar and drums. But, for the most part, it’s not a metal record. And yet, it’s more extreme than most extreme metal. That last Slipknot album is child’s play compared to this.

And, my god, if you get the chance, if Hayter graces your town with her presence on her tour schedule at any point, please go (unless you know doing so will adversely affect your mental health of course). I went to see her in London and it was an utterly unique experience. Part noise gig, part performance art, part group therapy session. It had a profound and lasting impact on me that actually saw me confront the reality of my mental health problems more directly and more healthily than I ever had done previously.

Now, I’m acutely aware of how problematic it is for me, as a cis, heterosexual, white male, to take art made by a woman in response to suffering and surviving horrific domestic abuse and somehow apply it to my own experience of mental illness, but I have to be honest about what Hayter’s superhumanly generous and vulnerable performance did for me. (From the looks on people’s faces in the audience around me, it clearly had similarly epiphanic effects on them.)

At the time of the gig, I was in the midst of one of the worst spells of depression I had been in for about a decade. It was debilitatingly bad. I was plagued by negative thoughts, complete lack of self-worth and near constant suicidal ideation. I have a good life, but I have a broken brain. And to some degree I’ve always felt like I’ve deserved a broken brain. I deserved that voice inside my own head that told me I didn’t deserve love, that all my accomplishments were meaningless, that I was a categorical failure.

When Hayter sang lyrics that were very clearly the repurposed words of her abuser, I recognised that voice inside my head, I recognised the very phrases my inner voice would use about me. I realised that my own brain was defeating me, and I resolved that from then on, I would do everything in my power not to let it. I am now on anti-depressants and in regular therapy and I am feeling stronger than I have done in a long time. And I can’t help but feel that, in part, I have Kristin Hayter to thank for that. She makes music that in its emotional candor and bravery renders most other music, hell most other art, trivial.

I have never gone through anything like what Hayter has gone through, nor would I presume to have been through anything remotely analogous. But listeners sometimes find things in art that are merely tangential to the artist’s intention, and that doesn’t render that experience insignificant. For me, it was life-changing, genuinely. Maybe it will be for you too. Please, give Lingua Ignota a listen (her latest record, SINNER GET READY, is another album of the decade contender). And, finally, on a personal and very sincere note: thank you, Kristin. – Andy Johnston

34.

Andy Stott – Luxury Problems

[Modern Love; 2012]

When introduced to Luxury Problems, you will probably be told that it’s a techno record. But, if you go in expecting the ambiance of a nightclub, you’ll be quite disoriented when you discover it’s more like visiting a haunted post-modern opera inside an industrial refrigerator. In fact, no matter what you’re expecting, Andy Stott’s music is always bound to confound.

It may be that Luxury Problems is considered ‘techno’ because the songs are usually undergirded by some kind of beat – though that pulse may not arrive until you least expect it. It might suddenly sweep across the production like an enormous fan blade, as on the opening “Numb”, or emerge, ever so gradually, from the depths of flickering static as it does on “Sleepless” – a song that then goes and clocks you over the back of the head with a second drop that sneaks up from behind. Stott’s use of beats are not necessarily to make you move, they’re just another textural element in this highly sensory world – one in which may at first be difficult to acclimatise to, but one that is impossible to disentangle from once swallowed.

Much like the black and white photos he uses on the covers of each of his works, Stott’s music is about shading; light intermingling with dark, clarity obscured by haze, greys colourgrading into different shades with each passing moment – all somehow ordered and arranged into a yawning, pulsating piece.

Luxury Problems marked Stott’s first collaboration with vocalist Alison Skidmore, whose words are sung beautifully, chorally in the case of “Lost and Found”, using a fairytale sing-song on “Hatch The Plan”, and affecting an R&B-esque croon on “Luxury Problems”. But, amidst this array of alien tones, that pure human connection transmits itself differently; it’s disembodied and unsettling, like a soul trapped amidst Stott’s constantly morphing world. Engross yourself in Luxury Problems and you’ll soon find yourself in there with her. – Rob Hakimian

33.

Tim Hecker – Ravedeath, 1972

[kranky; 2011]

Thunder clouds forming overhead. Ink spots bleeding colors onto paper. Ghosts heard muttering through concrete walls. A factory full of heavy machinery grinding away at night. Decaying old film reels unspooling from an abandoned projector. Nuclear fallout and the eerily silent aftermath. CDs warping and melting in an incinerator.

These are some of the things that you could say Ravedeath, 1972 sounds like. Taking a day’s worth of organ recordings in an Icelandic church, Tim Hecker (with the help of producer Ben Frost) dismantled his source material and folded it in on itself. Organ notes swim underneath hazy, dark washes of distorted synth, and as a whole Ravedeath, 1972 captures all the sinister, unsettling moods he’d been playing with until this point in his career.

You might hear what sound like delicate piano notes reverberating off the rafters on the settling and misty “In The Air” suite, or even scratches of guitar strings bristling on “Analog Paralysis, 1978”; maybe it’s part of the studio trickery, but when you get absorbed in the album (and you surely will if you have working eardrums) you never know quite what you’re hearing or how to describe it accurately. And to be honest, that’s what Hecker’s music sounds like. – Ray Finlayson

32.

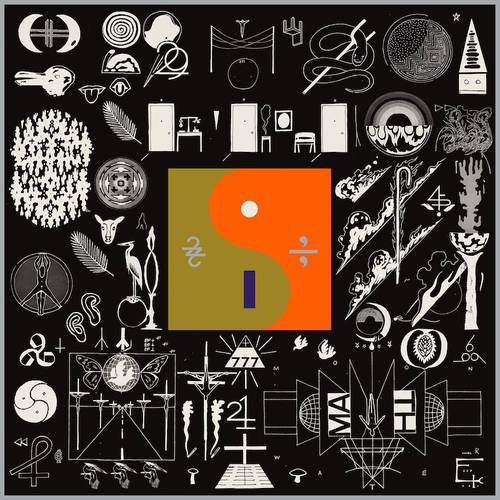

Bon Iver – 22, A Million

[Jagjaguwar; 2016]

The promotion and subsequent release of Bon Iver’s third album 22, A Million was a bit of a frenzy. After playing the entire album live at the Eaux Claire festival, Justin Vernon slowly dropped these fragmented ideas into our laps to piece together. What resulted was Vernon’s best album to date.

The band had already been working to perfect the auto-tune aesthetic that was humbly added to the Blood Bank EP and their previous album Bon Iver, Bon Iver. – not to mention Vernon’s other band, Volcano Choir, had done quite a bit with it. But nothing sounds like 22, A Million, and nothing else from Vernon will ever come close.

What most people hate about 22, A Million is what I love most about it. It’s Vernon’s most difficult work to get into, sure, but once you have you can’t get it out of your head. From the hum of opener “22 (OVER S∞∞N)” to the auto-tuned wail of “715 – CRΣΣKS”, 22, A Million manages to capture these broken feelings of its time. In competition with so many other landmark releases in 2016, I return to this more because, just like Low’s Double Negative, that feeling of disconnection and perpetual malaise with the status-quo never leaves me.

One of the final lines of the record sums up this disillusion that I still think rings true, “The days have no numbers.” They all just blend together now when we turn on the television, or we scroll through social media and witness the destruction of human decency and the decay of empathy. And that’s when I remember 22, A Million, when the world seems like shit, I can look to it and drift off in it’s fractured beauty. – Tim Sentz

31.

Danny Brown – Atrocity Exhibition

[Warp; 2016]

It was a source of personal relief when Danny Brown released uknowhatimsayin¿ and looked healthy and happy (and with trademark chipped tooth fixed) in the accompanying press photos. Because, holy shit, did Atrocity Exhibition give cause for concern.

The Detroit rapper had already established his MO on early mixtapes and his startling 2011 debut, XXX: head-spinningly leftfield beats paired with candidly sordid tales of poverty, substance abuse, and hustling to survive, spiked with filthy humor and off-the-wall wordplay, all revolving around that singular, cartoonish, strangulated yelp of a vocal delivery. 2013’s Old felt like a slightly unsure step: Brown’s personality split in half over two sides of vinyl: the introspective “ol’ Danny Brown”, spitting truths over modernized boom-bap, and the drug-fueled, party-starting monster, flirting with the larger than life sounds of EDM and brostep. On an individual song level, quality remained high, but it represented an uneven listening experience.

Atrocity Exhibition, on the other hand, is an irrefutable masterpiece: a perfect storm of lyrical content, creative flows and unique production. Taking cues from psychedelia, post-punk and nihilistic alternative rock, Brown and his collaborators created a rich musical stew that name-checked the likes of Joy Division and Nine Inch Nails in its unflinching depiction of one man’s self-destructive spiral.

Hence the concern I mentioned above: Brown isn’t afraid to illuminate the darkest recesses of his psyche, or confess to his worst behaviour. The thing to keep in mind when listening, is that Brown has been telling the grand narrative of his life over the course of his recorded output, and chronologically the events and headspace of Atrocity Exhibition take place before the healthier place Brown winds up in on Old.

This is probably why Atrocity Exhibition, despite its subject matter, never feels weighed down. It is, instead, buoyant with creativity. And no small amount of credit for this must go to producer extraordinaire, Paul White, who contributed the majority of the beats on the album (having already produced a number of Brown’s most iconic tracks on previous projects). Whilst many will argue for Killer Mike and El-P as the best MC/producer combo of the decade; for me, it’s Brown and White, no contest. Listen to “Ain’t It Funny”, “Dance in the Water”, or “When It Rain” and tell me if you’ve ever heard anything like it on a hip-hop album before, or since. This stuff is sui generis, and it’s utterly essential. It’s a downward spiral you’ll want to go down again and again. – Andy Johnston