Paradise will be mine!

SINNER: GET READY!

Have you sinned?

Have you not slept and not eaten for days?

Have you torn at your eyes in pain or sorrow?

Have you prayed for mercy or asked god to smite your enemy?

—

There is one moment, out of all the terribly, horridly beautiful moments of Robert Eggers’ modern classic The Witch, that carries the hardest emotional punch: when a child succumbs and leaves this world for the next, their mother, grief-stricken, falls down into her child’s grave. There she lies, hugging the lifeless body to her own. The moment of unbridled pain collides with the previous moments of the child’s death, in which they cry – arms extended and their face disfigured by pleasure – “My Lord, my love, my soul salvation, take me to thy lap!” These two moments frame the central struggle within the story; that of a family, which, spurned by the self-righteous arrogance of their patriarch, has to abandon their puritanical settlement and confront their hearts’ imperfections. And even when, finally, the titular Witch materializes, it is still the film’s struggle with the idea of sin that lights its powerful furnace. Is man righteous? Is sin but a veil behind which lies pure bliss and eternal fulfilment?

Say it: Man is corrupt! Man is deceitful! Kristin Hayter knows this. The inter-disciplinary artist who works under the name Lingua Ignota has explored the barriers of faith, abuse, pain and devotion in ways that breached the common laws of industrial music. Where usually male voices like Sutcliffe Jügend and Whitehouse croak satanic verses about despicable abusers, she has resurrected the shrieking throat of female survival. Shouting from the top of her lungs before suddenly diving into the range of opera singer, she twists and turns common ideas of victimhood, envisioning furious Erinye, whose bloodbath seeds the Earth.

Her way was unified – and in unification lies the danger of routine. But things couldn’t stay the same for Hayter: her body, this organ of revenge, failed her. Struggling, she reached out to strangers and finally was able to undergo a life-altering surgery. It was clear that whatever would follow couldn’t possibly retread the past.

SINNER: GET READY!

—

There’s not much to say now. It took her nine years to admit it openly – I wonder how long it took her to admit it to herself. There’s nothing to say, really, as the sheer weight of the confession seems to have changed the density of air within the room. So the only question that can be asked is put forward.

“Why DID you do it?”

She sighs, pauses. She avoids my gaze, looks to the side.

“As sick as it sounds, I just felt like… I earned it.”

Yes. There is nothing left to say. In the silence, is there forgiveness?

—

Eternity is a long time. Or is it? Adrianne Lenker only last year intoned “Not a lot / Just forever” and to the universe, humanity is but a brief song. To man, eternity always seems a threat. To those suffering, eternity creeps from day to day, feeding off their trauma. To those ascended to happiness, eternity promises ruin. Hob Gadling of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, the man who can never die? He sees his fortune and loved ones fade away, over and over again – then comes a new one, which too fades away. To man, eternity means nothing but constant reflection of their individual struggle.

It’s not in the realm of man where the term blossoms. No, eternity matters to the thereafter, the ether. If there is a god, and there is none, he will know those things that are eternal.

Here is one such thing: during the final of the survivalist show Alone, the winning contestant films himself, standing alone in the arctic. In solitude, he ruminates on his mother, his ignorance of her undying love for him. She passed while he was out, preparing for his trial. He could not attend her service. Now, at the end of the trial, it is dead silent – shields of ice swallowing the dead landscape. And then, he starts to hum a song. He speaks: “In the dead silence, you can hear your departed mother singing a hymn in church from 30 years ago.”

Hayter takes the man’s voice and ends “The Order of Spiritual Virgins”, the opening song on her third album, with it. This after having previously in the song sung “Hide your children / Hide your husbands”, and against the sound of hammering piano keys, repeated “ETERNALLY”; all caps. The hymn, how old is it? How many have sung it, what have they felt? Did it ever matter more than here, now, this moment, in the arctic, shielded by ice and caught by a single camera? Would it matter less if it wasn’t caught?

SINNER: GET READY!

Even when Hayter would smash her legs with lightbulbs on stage, there was always a bitter, poignant humor to her art. Her debut album All Bitches Die combined the imagery of Ms.45 with the sweet melody of festive hymns, while the follow-up, Caligula, used decadent imagery associated with rap and metal machismo and spawned the choral bliss of the line “I am the cunt-killer.” If this sense of irony is the axis of Hayter’s work, then her third album sees her rip out this axis, so that all her themes, symbols, allusions and curses spin freely into each other, cascading into fog.

On “The Order of Spiritual Virgins”, her request to swear eternal devotion is both a question and an order. It’s lines in manuscripts of obscure ascetic sects found in Ephrata. It’s Hayter beckoning her fans to submit. It’s the artwork pushing the artist beyond their comfort. It’s a lover drowning in the cruelty of their desire. It’s the son who, in total silence, hears his dead mother’s voice. And it’s the voice in “I Who Bend The Tall Grasses” – the thematic connective tissue between this third album and Caligula – who barks out “I have never loved him more than I do now, but I can’t do it again! / I have to be the only one! / I’m not asking you to understand, he belongs to me!”

Is this the same voice who, on “Pennsylvania Furnace” confesses “I’ve watched you alone in the home with your family”? It could be – but removed from all venom and anger, now full of love, accepting their fate: “Me and the dog we die together.” Spiraling off the legend of a vile ironmaster who burnt his beloved dogs, it transforms into a feminine “Norwegian Wood”. Is it jealousy that draws a spurned lover to set fire to the house, achieving an ideal Liebestod? Is it Freudian language for mental illness? Is it the burning pain of abuse trauma? After all, the dogs return and drag the ironmaster back to hell with them. What love is this that makes Hayter confess “I fear your voice / Above all others”, as her voice rises like a knife?

SINNER: GET READY!

—

All of a sudden, something next to me moved. As if looking back in time, I knew it was her. There she lay, writhing and convulsing on the floor, eyes on her. I bend down and pick her up. Her body limp yet twisting, shivering. Her mind gone. I hold her and whisper “Come back to me”. I look into her face. Her lids fluttering. Her eyes stare through me, then up, to the ceiling. She breathes heavy and in my horror, as her eyes roll back, I see her mouth extend wide into a smile of cosmic ecstasy.

Then her body goes limp.

—

One of the eeriest moments of the album comes in the sampled intro to closer “The Solitary Brethren of Ephrata”, as a faithful woman explains to a horrified inquirer that the Coronavirus won’t affect her, as she is covered in Jesus’ Blood. Hayter’s fascination with this delusional mindset doesn’t end at the song’s lyrics, where she twists common hymn-language into “No longer shall I wander / Ugliness my home / Loneliness my master / I bow to him alone,” to oh-so-slightly off-tune instrumentation. The blood of Christ appears in many of these songs, signifying the loss of reason. “I am covered with the blood of Jesus / Fear is nothing when the path is righteous”, she sings about it on “Perpetual Flame of Centralia” and asks in “The Sacred Linament of Judgment”: “O sinner have you ever had / The blood of Christ so lovingly applied?” Religion is awesome – and scary. Those claiming absolute faith, ultimate piousness and eternal devotion are often those whom its failing the most. It is the woman without a mask, misunderstanding Jesus’ blood as cure.

It is the shameful lover, misunderstanding his transgressions for love. Hear Jimmy Swaggart as he admits it all, sampled on “The Sacred Linament of Judgment”! Swaggart, a popular fundamentalist Catholic televangelist, confessed in 1988 on live air to being unfaithful with a prostitute, and proceeded to apologize tearfully for five minutes. “I have sinned against you, my Lord, and I will ask that your precious blood would wash and cleanse every stain until it is in the seas of god’s forgetfulness.” In the audience, a man is sobbing, wiping away tears. On “Man Is Like A Spring Flower”, we hear the side of the prostitute: “I know these tears aren’t real.” She explains how she watches Swaggart on TV, and how he was a different person when she saw him in real life – maybe the real him.

Fifteen years later, Swaggart was caught being unfaithful again.

SINNER: GET READY!

What’s transparent in Hayter’s use of the semantics of religion is that she divides between the words and actual experience. People evoke the name of the Lord, but they do so to reason their own moral failures – which, in light that all men are born sinners, seems irrelevant anyway. Yet, it is most poignant to those wearing piousness as a mask. On the other hand is the sight of godliness, which cannot be united with those words. To actually experience a spiritual event is pure cosmic fear. Symbolized by the blinding light of god, it is an overwhelming sensory shock that leaves the seer blind, babbling, convulsing, screaming – to drown and flounder, unconscious in utmost bliss! Is this the love of God?

Hinting at this, Hayter regularly uses noise to instil a similar dread and pain within her audience. But on her third album, she more often resorts to the slightly detuned sound of rural Appalachian instrumentation, such as on the opening notes of “Many Hands”, played on mountain dulcimer and shruti box. By mostly abandoning her signature sound, Hayter has sort of created a reverse Kid A, a photo negative of her previous work, set in a Sunday morning service of the 17th century. There are other stylistic references that could be traced here (to Tom Waits, Tori Amos, Nick Cave or Kate Bush’s more solemn moments), but this would distract from the thematic density and emotional weight that this album has in every moment. What could have merely been a reference to the days of pious puritans becomes a clear signifier of the inability to unite lofty religious aspirations with the failure of all things material. With its emotional journey, these nine songs should be experienced in one session, without distraction or pause, leading the listener through the nine circles of hell and back.

SINNER: GET READY!

—

I arrive an hour later. The door opens. Hugs. Sobbing. Forced smiles. “We just left the room for one call.” “Maybe that’s what he wanted – to be alone.” “Only the dog was with him…” Tears. The dog, in animal ignorance, tilts its head to the side.

Finally, I enter the room. Your skin so white… is there a shade of me in your face? “After all, now he seems at peace, doesn’t he?” I notice your uncovered feet and in a moment of sad delusion, I wonder if you’re cold. I don’t ask them to cover them up – they’re leaving anyway. So I sit down, and in the candlelight, it’s only us. Yes, there are definitely shades of me in your face.

—

The human struggle is eternal. Like all great artists, Hayter isn’t out to resolve the contradictions inherent to human nature – she finds ways to fold her themes in on themselves, so as to collapse them into ciphers. Those too fearful to delve into their own psyche will simply point at those songs as thinly veiled autobiographical treatises, yet as Picasso once said: “We all know that art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth – at least the truth that is given us to understand.” This truth can be the truth of god: of a story we made up and some of us feel, yet few make it their truth, even if they so claim to. Instead, they live a second truth, which only they know, until that truth consumes them like an inner flame – which also applies to the truth of love.

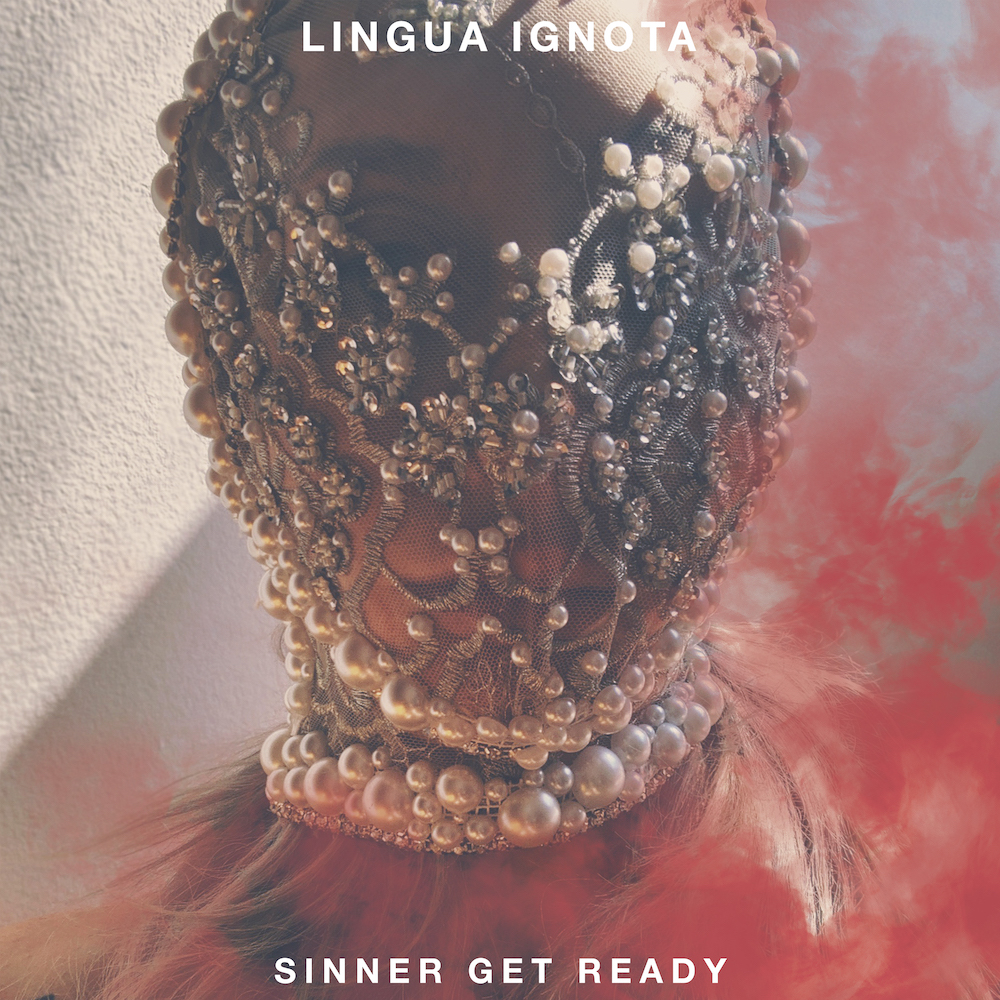

The collision of the inner and outer truth thus demarcates what makes us human. And in the end, what do we really know of Hayter? As Picasso continued: “The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.” And Hayter, after all, wears a mask on the cover of the album – but not the kind made superfluous by Jesus’ blood. So does Hayter even believe in God? Would you know what written word is truth or fiction if you face it? Does it even matter, if it connects to your truth?

God is. Like Darkseid is. But he is also not. His imago echoes between those left alone by him, on earth, his kingdom an immaterial idea attached to the material realm. And so we go on, we live, sin, love, are consumed by jealousy and mad with failure. Those things do not end with the dissolution of our individual struggle. Life is a brief song that one day will be over, and death will not solve this, nor will god reveal himself to us. In the far future, in hundreds of years, when all that is left of the now is ashes, nothing will have changed, yet everything will have changed. Man will still hurt, abuse will still occur. As the first Roman catholic priest of Centralia once said: one day, only the church will remain in it. The concept of god will linger and the perpetual flame of Centralia will burn on and on, like the fires of hell.

And yet, these nine songs will still speak to those willing to listen, speak of the arrogance of those claiming superiority, of the delusion of lovers and anger of those left by the wayside; of the loneliness of the mortally confused, and of the jealousy of those left behind.

—

You have sinned.

You have not slept and not eaten for days.

You have torn at your eyes in pain and sorrow.

You have prayed for mercy and asked god to smite your enemy.

SINNER: GET READY!

Do you want to be in hell with me?