Prurient – Frozen Niagara Falls

[Profound Lore; 2015]

Whether working as Prurient, Vatican Shadow or Rainforest Spiritual Enslavement, Dominick Fernow’s music always lives in the shadows. But, with his 2015 double album Frozen Niagara Falls, it felt like he stepped into the light for a moment – and the figure standing there was someone who hadn’t seen light for decades, now looking like a hideous amalgamation of Terminator, Swamp Thing and suicidal tendencies made corporeal.

Fernow yelps, gutturally screams and raspingly sighs throughout the album’s 90 minutes, but his words are barely audible beneath the layers of coruscating fuzz and ear-piercing tones, which effectively blanket him like unshakeable cloaks of depression, animate his rising tides of panic, or deepen the endless black hole of hopelessness within him. Even if you were to look at the lyric sheet, the words found there only make the whole experience even darker: meditations on his mother’s suicide and dreams of drowning are regular themes.

There are seeming moments of beauty that crop up, but ultimately are also subsumed by the pervading despair. Harp flecks on “Dragonflies to Sew You Up” sparkle on the edges of the cataclysmic noise, like hope that’s just out of reach for the singer. “Traditional Snowfall” sounds pretty in title, but is one of the most terrifying onslaughts of cross-talk feedback and features Fernow screaming “I want to rip out your lower back / And suck the air out of your lungs / And wrap my hands around your neck / And collapse your throat / And squish your thorax.” Even a track with the title “Wildflowers (Long Hair With Stocking Cap)” turns out to be just a series of scratching and scraping noises. Suffice it to say, there’s not much sunlight to be found on Frozen Niagara Falls. – Rob Hakimian

Purple Mountains – Purple Mountains

[Drag City; 2019]

Even before the passing of an absolute legend in David Berman, it was hard not to listen to his first and final work under the Purple Mountains name without deep concern. One could point to the alarming refrain of “All My Happiness Is Gone” with eyes closed, or dig a little deeper at the philosophical gloom enveloping the opening line of “Nights That Won’t Happen” or even… you get the point.

Less than a month after releasing his final project, Berman tragically took his life, leaving listeners not with pieces to pick up, but a parting message that was clear as day. As Berman, with his mind seemingly already made up, yearns for meaning by shouting for help inside a dark tunnel, listeners who decide to trek through Purple Mountains will find themselves grasping at the songwriter as he slips away, knowing damn well that they can’t do anything to prevent what, in fact, happened. It’s a surreal experience, and one that’s hard to swallow with the knowledge of his fate.

An album that could top either the saddest records list and, in this case, the darkest, Purple Mountains occupies a space few can. No, the music at hand doesn’t send shivers up your spine or throw you into a mouth-frothing frenzy when listening. This is a straightforward indie-folk project with a deceptively uplifting sound, tragically belied by sheer reality — death without knowing what, if anything, lies ahead. – Kyle Kohner

Redman – Dare Iz A Darkside

[Def Jam; 1994]

Before Doctors West or T.C., there was Dr. Trevis, the medical guide to bring you into the depraved world of Dare Iz a Darkside, Redman’s second album; an experience so intense, its creator hasn’t been able to bring himself to listen to it since he made it.

What’s amazing about Darkside is how it shows a downward spiral not through misery but through euphoria. Throughout it all, Reggie Noble is reaching new highs in terms of boasts, and as his confidence grows, it becomes devastatingly clear that he has potential Icarus ideals, even as the sun remains far out of reach. Over his own twisted production, Redman sounds like he has to wrestle with his demons as they’re being conjured. There’s no moralizing to be found, just a potent examination of mutual ambition and destruction. – Brody Kenny

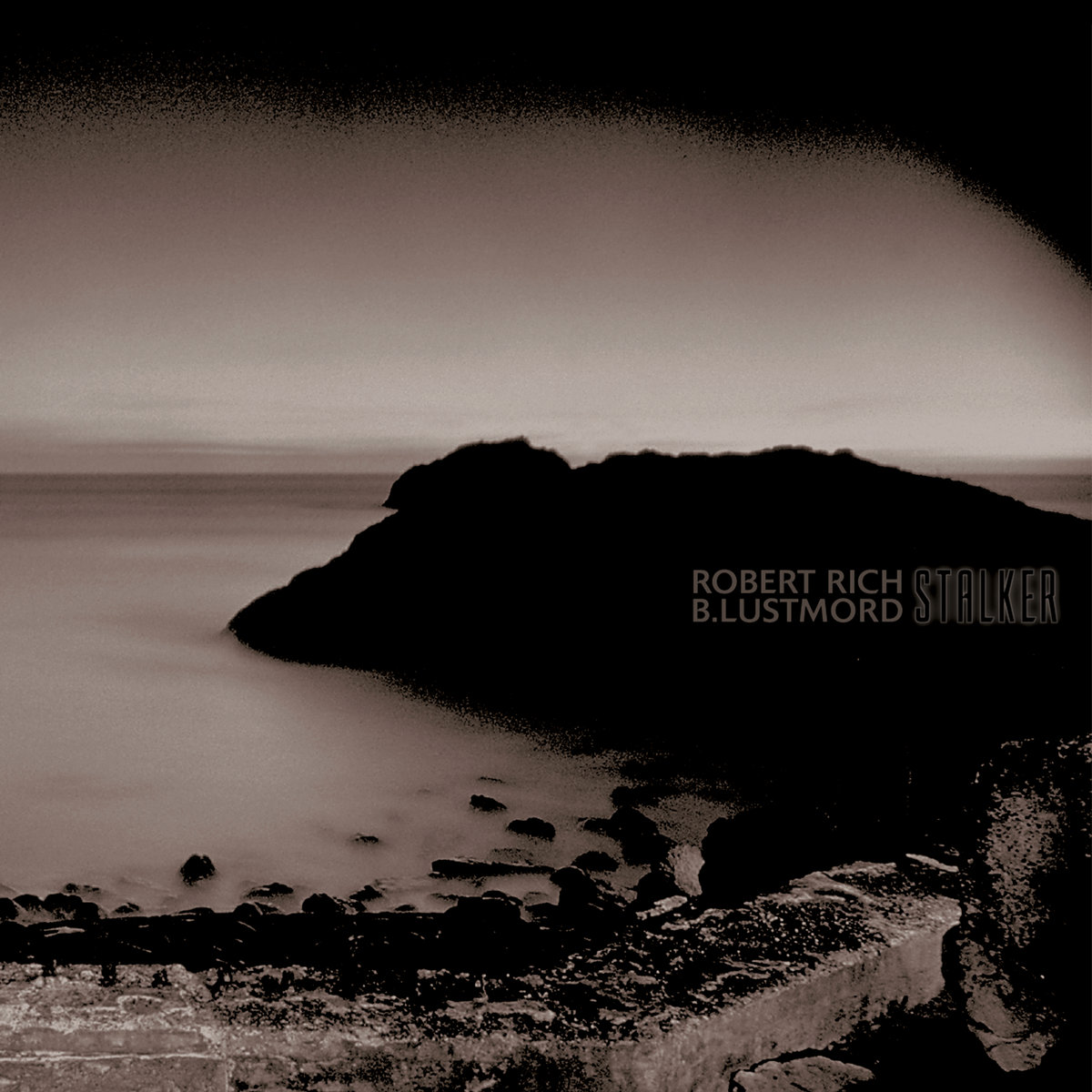

Robert Rich & B. Lustmord – Stalker

[Fathom/Hearts of Space; 1995]

Stalker begins with a transporting noise, like you have been beamed onto some unknown planet. The atmosphere is misty and heavy. You hear bogs and swamps burbling, and creatures crying out in the faraway distance. Over almost 70 minutes Robert Rich and B. Lustmord take you on a journey through this terrain; they are your invisible guides urging you towards new sights you can never quite make out through what feels like an impenetrable fog.

Inspired by the 1979 Andrei Tarkovsky film of the same name, Stalker is a masterstroke in the dark ambient genre. The two artists expertly create a real sense of gloom and dread, and throughout its runtime there’s an unshakeable feeling that someone (or something) is watching you. On “Synergistic Perceptions” it sounds like you’re cautiously walking through an abandoned, rained-out warehouse, complete with water dripping, electrical wires fraying somewhere, and foreign voices whispering in the distance. You might hear a tangible noise here and there, but it never puts you at ease. The unsettling bobbing rhythms at the start of “Delusion Fields”, the low bellowing foghorn on “Hidden Refuge”, or the recurring flute noises across the album only add to the mystery of what exactly is around you.

Granted, Stalker does wear its age quite clearly, and if not entirely immersed it can sound like the unnerving backdrop to a creepy horror or murder podcast. Still, it’s so full of detail and layers, moving seamlessly between an industrial clamour to a more organic simmering (very much like Brian Eno’s Ambient 4). Ultimately though, it’s impossible to deny its darkness. From that monochromatic album cover to the wispy, alien drones, to the occasional low, moaning rumbles of noise, Stalker is unremittingly bleak and sullen. – Ray Finlayson

Scott Walker – The Drift

[4AD; 2006]

It feels as though one could write a whole book covering the darkness of any one of Scott Walker’s three — or four, if you count with collaboration with Sunn O))) — final albums before his unfortunate passing in 2019. After taking a long break following 1984’s Climate of Hunter, Walker returned in 1995 with a decidedly darker, bleaker, and more sinister sound, with the polarizing Tilt. Where once Walker was known for art rock and pop, he then swiftly became synonymous with spooky soundplay, nightmarish imagery, and his aged, husky croon of a voice. And while his final solo album, 2012’s Bish Bosch, had its fair share of zonked out dirges, Walker perhaps never reached a pinnacle as frightening, austere, and oddly beautiful, as he did on his 2006 album, The Drift.

Right off the top with the gnarly, 70s-reminiscent electric guitar strums, chilly horror movie strings, and chase scene drums, “Cossacks Are” drops us right into the thick of things, topped with Walker’s warbling, terribly dramatic voice, wavering like a zombie hummingbird. Despite being, possibly, the closest the album comes to ‘accessible’, the track is both a good sample and also a bit of a feint: following up this driving opening salvo is the 12-minute “Clara”, which gives us unearthly, seasick strings, as Walker sings in grotesquely poetic detail of Mussolini’s murder and subseqent public hanging alongside his lover, Claretta. And things only get darker from here.

Across the nearly 70-minute runtime, the atmosphere of The Drift doesn’t let up. There’s an eerie tune that’s about both Elvis Presley’s deceased-at-birth twin and the 9/11 terrorist attacks (“Jesse”); there’s truly horrifying minimalist soundscapes of plucked strings and mournful horns (“Cue”); and, perhaps most infamously, the distorted, guttural, Donald Duck-esque cries at the end of “The Escape” that are scary enough to haunt you for days. That The Drift ends with a song as simply lovely as “A Lover Loves” is almost humorous, which actually might be a secret ingredient to the proceeding affair: was Walker a musical sadist, or did he just have a blisteringly dark sense of humor? As he “psst psst”s his way through the pastoral finishing moments, I’m inclined to lean to the latter, but it’s honestly unclear, and either way, The Drift ends up being a nearly-impenetrable tome of weirdness and horror. Walker was truly unlike anyone else creating music (or ‘music’) in the 21st century, and this album stands as a bright testament to his unique gifts. – Jeremy J. Fisette

Scout Niblett – The Calcination of Scout Niblett

[Drag City; 2010]

The word ‘calcination’ is not a very common one. Basically, it’s a process where one heats a material to a very high temperature to rid it of impurities or volatile substances. So, it’s only fitting that on an album where British singer-songwriter Scout Niblett claims she’s calcifying herself, she opens it with a blaring screed of her trusty electric guitar. Niblett had been known to engage in some noise every now and then on her numerous earlier records, but mostly she was known for either making humble guitar-and-voice or drum-and-voice songs. On Calcination, however, most of that goes out the window for a silvery, moonlit excursion through some very dark and dooming soundscapes.

“Just Do It” opens with a trademark Niblett riff: simple, repetitive, and direct. When it breaks, it continues on in a quieter volume, until she intones, “And the voices said ‘just do it’ / And I think I agree / ‘Cuz someone’s got to do it / And it might as well be me.” This is all delivered in her very specific, slightly-mewling style of singing. There’s an off-kilter, almost early-Joanna Newsom-esque, childlike coloring to her vocals, and it contrasts against the album’s desolate, spare landscape uncomfortably and yet, somehow, also perfectly. “Just Do It” exists almost entirely upon her guitar playing the same chord progression over and over, with intermittent bursts of volume and fire. That minimalism is part of what gives the album its night time mood, which overrides even the album’s prettiest moments.

And there are pretty moments. “Bargin” ends with a beautiful refrain of Niblett singing pleadingly, “Let me play! Let me play!” And “IBD” has a peculiar but quite lovely melody at its center. Otherwise, though, much of this album is pared back to the bare necessities, almost elemental. Sometimes there are drums crashing in, such as on the up-and-down ride of “Kings”, the sudden drop-in at the end of “Just Do it”, or the only drums-and-voice track here, “Lucy Lucifer,” which subverts its nursery rhyme melody with its austerity. Most of the time, though, it’s Niblett and her guitar. The production is airless, dry as Death Canyon, almost humid; her voice sometimes sounds like it’s being recorded from behind a pillow. As the nine-minute closer “Meet and Greet” ends in a total blaze, it cements this as being Niblett’s oddest, most aggressive, and yes, darkest album yet. – Jeremy J. Fisette

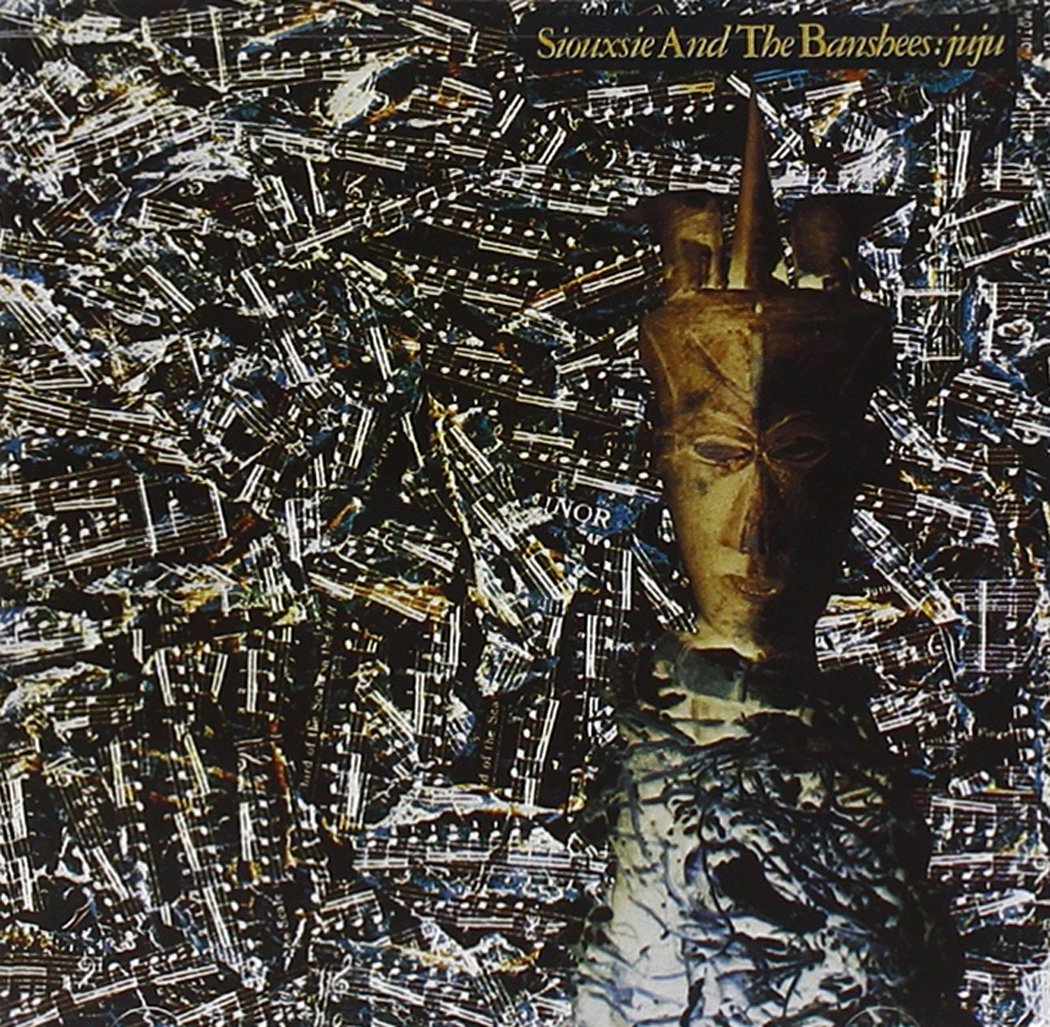

Siouxsie and the Banshees – Juju

[Polydor; 1981]

What do you get if you cross John McGeoch’s swirling guitars, references to serial killers, and oblique allusions to the Japanese horror film Onibaba? Siouxsie and the Banshees‘ Juju, that’s what. The Banshees’ first two records, The Scream and Join Hands, nailed the sense of suffocating claustrophobia with hard metallic edges and punkish force, but Juju‘s darkness is more sophisticated and more complex. The melodies are almost pop (“Spellbound” and “Arabian Knights” became hits) and there’s a frenetic, rhythmic energy propelled by Budgie’s drumming – but there’s no denying that it’s an altogether dark, bewitching sound. Siouxsie’s voice is all gothic opulence, the songs speak of being entranced by ragdoll dances, of the Yorkshire Ripper trawling the streets, and of taking a severed head back to your flat as you do. But all with a real grim vitality rather than tongue-in-cheek quasi-doom. It reaches a climax with the brutal, creepy “Voodoo Dolly” with its bewildering sea of hissing “listens.” Juju, in its gothic splendour, is peak Banshees darkness. – Matthew Barton

Slint – Spiderland

[Touch and Go; 1991]

The first couple of seconds into “Breadcrumb Trail”, the opening track off of Slint‘s monumental final album Spiderland, are as deceptive as any introduction to any album ever made. A mere two seconds of David Pajo’s twinkling guitar beauty quickly give way to 40 minutes undergird by dismal post-rock and arcane stories of alienation and yearning — not for “what was,” but for “what never was.” During the making of Spiderland, frontman Brian McMahan survived a near-death experience that left him to spiral depression with the nagging life-long question of “why didn’t I die?”

This existential dread continues to haunt past the confines of McMahan’s toiling mind and into an alternate reality where Spiderland wasn’t the band’s farewell. Questions are still raised regarding if Slint had stayed the course, would Spiderland be the cult classic it exists today? And if so, would the Kentucky band have embraced relative fame as the peak of ’90s alt-rock; specifically, math-rock and post-rock, lurked around the corner a few years later?

Sometimes the what-ifs in life are the biggest boogeymen to humankind, and Spiderland is full of them, formed into an inescapable web for listeners to willingly fall into and become prey. With added themes of fleeting childhood, fatherlessness, and depraved sexual hunger consuming the band’s ominous farewell, this elusive death note is a persisting nightmare that becomes murkier as years pass. Why? Because Spiderland is not bound by time. It presides over it like a heavy shadow—amorphous—looming behind, strutting cryptically closer, hunchbacked and finger lurching forward with nails long and unkempt. It taps you on the shoulder, but you abstain from looking backward. It’s an evocative and bleak presence that continues to dwell 30 years after its release, and of course, Slint’s untimely end. – Kyle Kohner

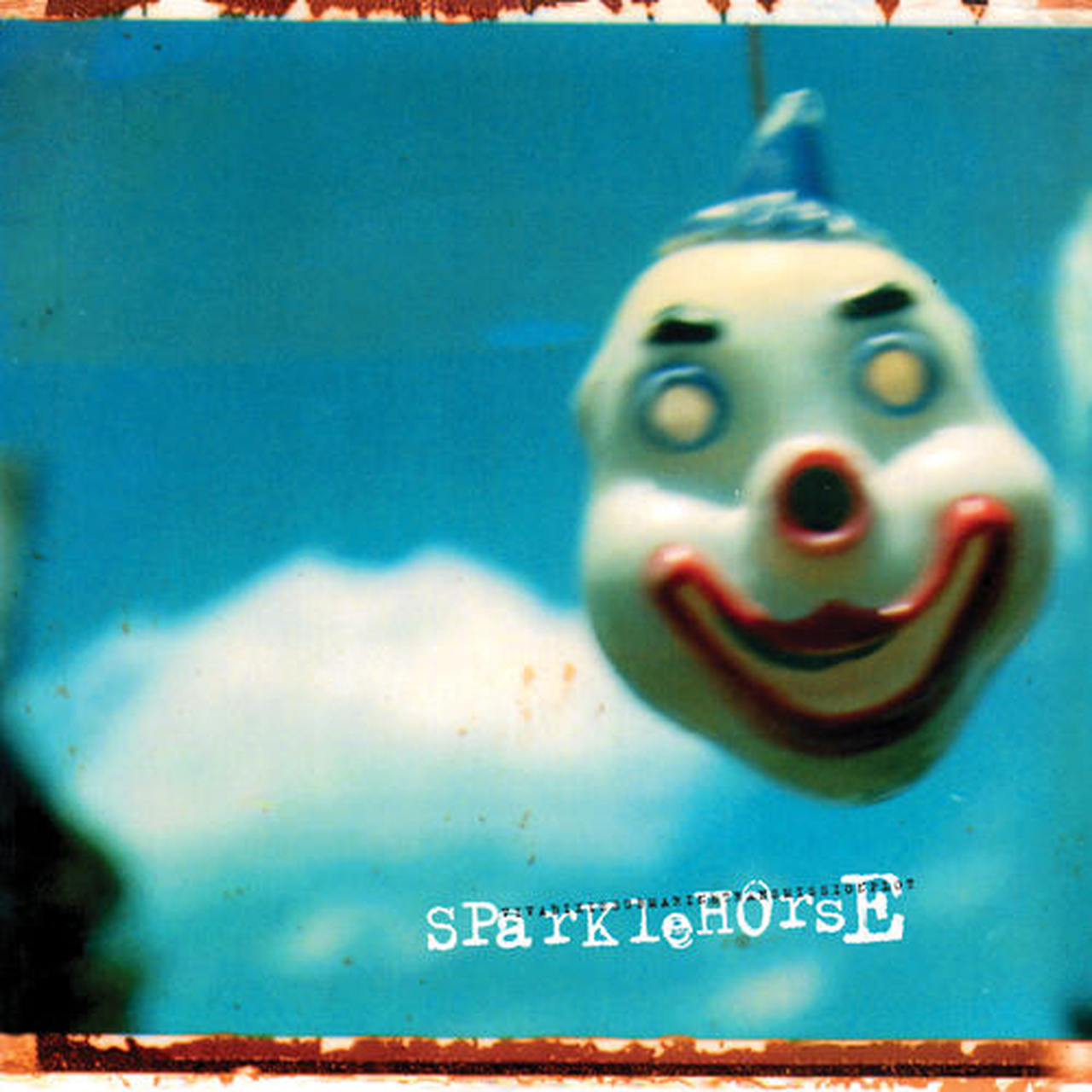

Sparklehorse – Vivadixiesubmarine transmissionplot

[Capitol; 1995]

There is a recognition of despondent beauty on this album, a template which Mark Linkous continued with on all subsequently pained Sparklehorse releases that followed this, their wonderful debut. The sadness permeates throughout, yet the darkness is driven by the instrumentation just as much as the lyrical subject matter. Suffocated, wheezing noises emanate from a range of detuned guitars, children’s toys, and gasping fairground sounds that serve to highlight the fact that vibrancy is short-lived, yet there is permanency in decay.

Vivadixiesubmarinetransmissionplot has smatterings of ennui-driven pent-up frustration with “Some Day I Will Treat You Good” and “Rainmaker”, but the overriding feeling on this album is one of acceptance of the inevitable heartbreak that follows us around, of the relinquishing of all hope. Some people find beauty in abundance in the feeling of genuine deep-seated despair, and this album is for those who revel in the darkness of existence and appreciate all of the pain that comes with it. – Todd Dedman

Sunn O))) – Black One

[Southern Lord; 2005]

While there certainly is an image of the metal genre as this dark, foreboding territory, a lot of metal can be intentionally goofy and really fun. There’s rarely an album that doesn’t sport an element of humor, even if it is decidedly dark or macabre. Now, in the case of Sunn O)))’s Black One, the only levity to be found is in the song titles. “Orthodox Caveman”, “Cry for the Weeper”, “Candle Goat”… It’s evident the band is winking at the audience here.

However, everything else about the album, from its foreboding artwork to the constantly hellish forms of droning guitars and anguished screams, is of striking, hellish intensity. Emulating aspects of the black metal genre into their drone landscapes, the compositions here mostly consist of rivalling textures: long underlying guitar tones build the fundament upon which quite dynamic riffs develop a sense of enormous spaces, conjuring images that are both claustrophobic and maximalist. Take “It took the Night to Believe”, which almost feels like it conjures the very idea of metal from the subconscious fears of somebody who has never heard the genre and only knows tales of it. It’s scary, nightmarish stuff that still retains a majestic quality usually only found in classic music.

And then there’s the vocals. Oh god, the vocals… Aided by a host of guest vocalists, Sunn O))) filter their macabre growls, vulgar screaming and anguished cries to add surreal, ghost like qualities to these performances, which are nothing short of demonic. Especially “Cursed Realms of the Winter Demon” ends up thoroughly haunting, with what sounds like an Uruk-Hai cursing the absent gods which made him over the atmosphere of an icy landscape. And then there is “Bathory Erzsebet”. Trying to emulate the last moments of the dying, walled in countess of the same name, the band came up with the idea of trapping claustrophobic metal vocalist Malefic in a casket, so as to conjure authenticity for his performance, which, when it finally starts (after long, agonizing moments of quiet ambience) sounds so drained and lifeless that it’s genuinely troubling, even without knowledge of its intentions. It ends an album that is often epic in its scope and sound in a place of genuine loneliness and inspires reflection. – John Wohlmacher

Svarte Greiner – Knive

[Type; 2006]

Erik K. Skodvin has put out many albums over the years, whether under his own name, the alias Deaf Center, or Svarte Greiner. He’s known for his long-form pieces of sound play, abstract minimalism, and ambient music, sometimes dabbling in more droning or orchestrated pieces. His 2006 album as Svarte Greiner, Knive, is one of the oddest, most abstract pieces he’s put out, full of unnerving atmospheres, brittle textures, and haunting melodic passages passing through like spectors.

Opener “The Boat Was My Friend” immediately sets us off on an unstable footing, with woozy electric guitar rippling in and out of focus, a percolating percussive tattoo rattling underneath, and a sliding cello line accenting along the way. The fuzz and room tone of the recording flits in and out as the bubbling textures jut up and down, left and right, never finding solid ground. “My Feet Over There” has a similar trick, with what sounds like an electric guitar (possibly?) being scraped up and down with a blade, then recorded in a very gritty, lo-fi fashion. The effect is like nails on a chalkboard but worse, and yet somehow, it’s instantly alluring. It’s almost like a skeleton playing his own bones.

Speaking of, there’s literally a song called “Easy on the Bones”, which has a deep bass ambience and a sawing sound chugging away, while eerie strings sigh in the background. The longest track here, “The Black Dress”, sounds like it’s soundtracking the climax of a particularly sinister horror movie. The dreary, driving organ sound is accented with clanging chimes and a thin layer of fuzz. It’s the most full-sounding track here, but even this one ends in more than a minute of wind noise, microphone rubbing, and droning tones.

Knive is a good album to put on at Halloween parties. It’s just insistent enough to act as more than background music, but pay it any attention and you’ll be deeply creeped out. As “The Dining Table” sends us off with pulsing percussion, some Hereditary-style strings, and totally haunted wordless vocals, it’s clear that the chills that Skodvin forced into your spine surely won’t be leaving any time soon. – Jeremy J. Fisette

Swans – The Glowing Man

[Young God/Mute; 2016]

If there is anyone in any music scene whose entire discography has been engulfed by a mystical, at times terrifying darkness, it is none other than Michael Gira. Swans, as well as Angels of Light and his solo music, all bear this gloom and there is no objective way of identifying the single darkest album in this discography. On this one I shall go with my personal experience of Swans, for me, The Glowing Man has become the darkest album of all of Gira’s works.

The 2010s incarnation of Swans saw them put out multiple impressive records, starting from 2012’s The Seer and ending with 2019’s leaving meaning. The Glowing Man is the second to last album in the series, and it sees Gira and co delve deepest into terror. Words on this album for the most part don’t bear literal meaning, rather they’re sensed; Gira’s powerful vocal delivery and the soundscape created by the whole band give almost a feeling of a pagan ritual in a dark forrest. The words are predominantly used to sonic effect, as opposed to semantic. This is among the darkest records ever produced and there are really no words that can describe just what kind of a transformation this album puts the listener through, so I shall end here. It needs to be heard, as it cannot be explained. – Aleks Smirnov

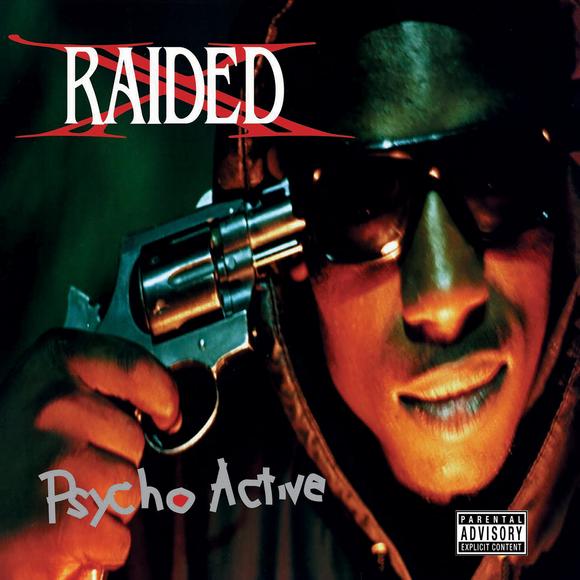

X-Raided – Psycho Active

[Black Market Records; 1992]

The starker brother of the aforementioned Season of da Siccness. How so? X-Raided is no Brotha Lynch Hung, he has very little interest – or use – for cartoonery. He’s all reality, all the time, even when he sounds over-the-top.

Just how much reality, you ask? Well, he was arrested for the murder of the mother of one his gangland enemies the day before the release of this very album. That gun he’s brandishing on the cover? Police have long believed it was the actual murder weapon, but have been unable to prove it – it was never recovered.

For all the gangster posturing of hip hop, the genre has perhaps never more closely plunged into the reality of the violence and depravity it indulges in than Psycho Active. If X-Raided isn’t heartless, he’s been rendered damn near close. The uncompromising vision here is as unsettling as it is all-consuming. If Ice Cube was having a “Good Day”, this is the one so bad you might wish you’d never heard about it. It’s hard to stomach, but it’s impossible to look away. – Chase McMullen

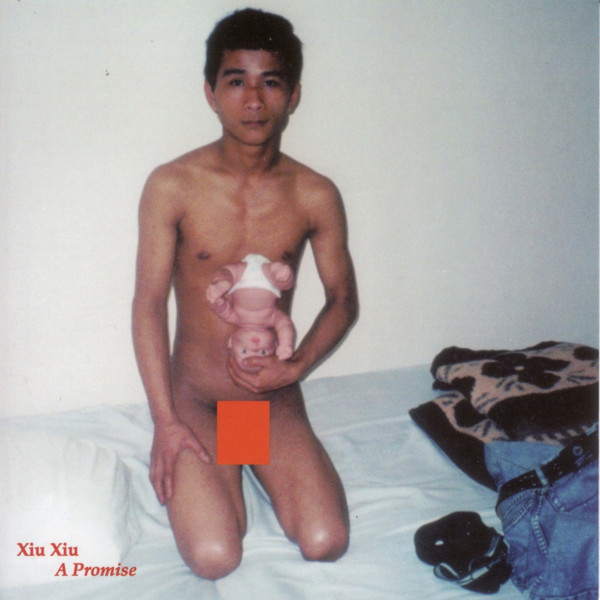

Xiu Xiu – A Promise

[5 Rue Christine; 2005]

To say A Promise is not for the faint of heart, or any Xiu Xiu record for that matter, would be a complete missed opportunity to call it what it really is— jarring as fuck. Honestly, there are only two types of listeners one could recommend this album to: someone who has either cleansed their pallets and hearts of all dark thoughts and can handle something as depressing as a Xiu Xiu album, or an individual who is in an utterly shitty headspace and needs to indulge their depression with the staggering shudders of Jamie Stewart’s uncanny songwriting. The latter should be a last resort, as Jamie’s words about suicide can be misinterpreted.

When considering the topical core of A Promise and the devastating reminder Stewart’s father taking his life only a few months before it was released, it’s easy to hear why. Never mind the glitchy misery that overwhelms this art ‘pop’ record; Stewart is enough by himself to take listeners into a space most dismal. Though Stewart’s own insecurities and ideation are bared for all to see, albeit obscured by his monikered bizarreness, his quivering voice simultaneously operates as the haunting ghost of his father, who Stewart brings back to life to reconcile family matters, suppressed sexuality, abuse, and commitments gone awry. It’s like a tense family dinner table scene in a horror film, except you know the fate and the pain that’ll come to pass for the characters when the director yells cut. Nevertheless, hope and life prevail. Despite the heaviness and feral messiness that engulfs Xiu Xiu’s second full-length effort, A Promise miraculously vouches for others to choose life. – Kyle Kohner

Z-Ro – Look What You Did to Me

[Fisherboy; 1998]

Z-Ro has no interest in grim antics, no desire for violence beyond the necessity for it. To be sure, the Houston legend has long since morphed into a hometown hero, omnipresent and reliable. His debut, however, was an entirely different story, still plugged directly into the deep sense of pain he’s often channeled since. It’s also his masterpiece.

The beats are, surely by necessity, minimalist, just enough to boost the words. The words, after all, are the focus here. Nearly seeming to lose his voice at times, Z-Ro pours every bit of his soul into the album, confronting the absolute peril of his life without restraint. “And 2 My G’s” sees him juxtaposing a hook of “don’t ya worry about a damn thing,” with verses of loss, fear, and bruised nostalgia.

Look what you did to him, after all. Who’s the culprit? His enemies. His friends. His family. His surroundings. His own weakness, his addictions. Therein lies Look What You Did to Me’s great power: it still all too readily speaks to the realities confronting far too many of our youth in poverty. It leaves him feeling as if, “This world is not my home, I’m just passing through.” It’s as painful as it is pained, as essential as it is undeniable. – Chase McMullen

Zero Kama – The Secret Eye of L.A.Y.L.A.H.

[Nekrophile Rekords; 1984]

Considering the prevalence of horror fiction to come up with bloodcurdling mythologies about the origins of art, it’s surprising how few albums there are whose recording are an actual horror story. Besides the usual turmoil of interpersonal struggles, trauma that inspired a specific lyric or maybe a painful injury that informed a performance, there aren’t really any scary stories surrounding recordings that would suit a campfire lit horror retelling. Besides this: The Secret Eye of L.A.Y.L.A.H.. It marks the rare case in which an album’s unsettling sound actually reflects its creation. According to Zero Kama‘s sole member Zoe DeWitt, it goes something like this: following the dissolution of Throbbing Gristle and a short lived stint in Genesis P’Orridge’s Temple ov Psychick Youth, DeWitt felt inspired by pen-pal John Balance to found her own label. Under the name Nekrophile Records, DeWitt released a small number of tapes on red paper, adorned with occult symbols. Leaning into tribal and ritualistic sounds, the small label managed to gain traction in the esoteric sphere of Industrial music, yet DeWitt couldn’t find the right outlet for her musical ambitions.

And so one day, DeWitt embarked to a charnel house in the Austrian countryside a friend had recommended. There, DeWitt found a number of bones strewn about that she carried home and – yes – fashioned into instruments. What sounds like a grotesque fairytale is actually real, as DeWitt is still in possession of a few of those instruments (she gave away the majority after recording), which she presents during lectures. The ensuing music can best be described as Lovecraftian: the rhythmic pieces mostly consist or ritualistic drumming, obscure voices and strange flutes, borrowing from styles found in Africa, the middle east and various island states. Of course, this corresponds with DeWitt’s own magickal interests – which came to the forefront during live performances – but also accurately represents the chaotic energy of the Industrial genre and queer sensibilities of their artistic influences, such as William Burroughs. – John Wohlmacher

Listen along with our Darkest Albums Spotify playlist