Humanity has always sought out shadows to articulate that which is impossible to manifest in light. Harkening back to the oldest fundaments of mythology and religion, there existed dualities and unspeakable questions directed at the void. It’s there, in the lore of chthonic gods and fairytales of monstrous creatures, in fables and rituals. It developed, evolved into paintings of fallen ones and nightmarish apparitions, half-remembered legends. Words passed down for generations were sealed in scrolls, then books. They became plays, performances, finer art and song. Some couldn’t bear their sight, some shuddered in their presence, while others found in them comfort, or even awesome beauty.

What is it that reflects within us when we see Goya’s Saturn, when we read Milton’s Paradise Lost, watch Lars von Trier’s Antichrist or listen to Throbbing Gristle’s Second Annual Report? To some, those works are impossible to analyze, so all-consuming is their almost cosmic strength of suggestive power and bleak imagery. Others might argue that there is a deep, mystical truth within the hidden intensity. Observed closely, they all reflect struggles with a society that is, ultimately, flawed, obscuring the functional to highlight the untold and unacceptable that is usually bound within the shadows of purposeful ignorance. Yet, as one of our writers put it, within this realm of borderline traumatic art, there can be hope, the possibility of comfort even. Trauma is, itself, a shapeless ink blot that consumes many confronted with the inconsumable. If an artist manages to capture our fear in a definitive way – give shape to the otherwise shapeless – it somehow is transported out of the unspeakable and into the open. Like Pony Pinkie Pie once argued: if you shine light on that which bothers you, it might elicit great laughter and alleviation. Maybe that’s why those artists in the usually drab and dire power electronics and industrial scene often happen to have magnificent humor, revealing their stories of terror and debauchery as macabre consequences of societies that look away.

But how to define an album as truly dark, given that music is one of the most shapeless and elusive art forms, often lacking visual components? Beats Per Minute’s staff has taken that question and come to the conclusion that there is no such thing as a definitive when it comes to ‘the darkest albums ever made’. While it would be easy to just rack up a list of especially grotesque, draining and joyless offers from extreme genre artists, we decided to focus on individual suggestions of what our writers feel is, to them, a dark album, and then expand upon its effects on them. We hope that in this approach, our readers might find new perspectives on and insights into works that are usually left out of canonical discourse. It also allows each writer to shine light on how art can expand on those aspects of the human condition which might be emotionally troubling, but are resolved within artistic reframing, finally allowing catharsis.

So grab a cup of tea, hold on to your favourite My Little Pony plushie, and venture with us into the nether realms of the darkest albums according to the BPM team. – John Wohlmacher

Listen along with our Darkest Albums Spotify playlist

A.A. Williams – Forever Blue

[Bella Union; 2020]

With her debut album, 2020’s Forever Blue, A.A. Williams emerged as one of the more nuanced vocalists of her generation, seamlessly crossing thanatoid pop with etheric and grungy atmospheres. From the reverb-y piano chords and moribund textures of opening track “All I Asked For (Was To End It All)” to the sinisterly etheric and soaring vocal wails of “Melt”, Williams irresistibly blends a sense of profound longing and despair while evoking a grimly transcendent beauty.

“Fearless” opens with shimmering guitar chords and Williams’ expansive voice, transitioning into heavily distorted and oppressive sonics, including snarling vocals from guest-singer Cult of Luna’s Johannes Persson. “Love and Pain” paints a vampiric portrait of romantic enmeshment and epic codependence, Williams singing, “Still, always, it isn’t the same / I’ll steal away the light that you gave / Find a way to hate me again / Till I can give you love and pain.”

The album closes with the ironically titled “I’m Fine”, which opens with Williams’ languishingly resonant voice accompanied by wispy piano chords – much as in the opener – singing, “Please, forgive me / I’m broken and I can’t decide / If I’m worthy of / All the love you’re threatening to hide.” A gossamer cello part adds to the track’s high-romantic sound and feel. One of popular music’s stellar debuts, Forever Blue memorably navigates uncertainty, loss, and heartbreak, plunging a listener into darkly reflective realms while offering ecstatic catharses, that sense of wholeness, however fleeting, that sublime art can facilitate. – John Amen

Brotha Lynch Hung – Season of da Siccness: The Resurrection

[Blackmarket Records; 1994]

If you let Brotha Lynch Hung tell it, this is the album that will, “have you murderin’ yo bitch.” I only open with those words as something of a warning: if you’re already offended, you do not want to listen to Season of da Siccness. We’re talking cannibalism, we’re talking “bloody clit” eating, murdering babies, uh, you name it.

It’s not without reason that some view Brotha Lynch Hung as the damn creator of Horrorcore. We can argue all day as to his finest statement – it may well be the comparatively mellowed out, funky, underheard classic Loaded – but there’s no question that he never got darker (or grosser) than here.

So what’s to recommend it? First, there’s the hollowed out, slowed down G-Funk production, like a proto-Dr. Dre gone demonic. Posse cuts such as “Locc 2 da Brain” not only truly bump, but offer reprieves from the insular, oh-so-alone nature of his toiling.

Then there’s the double-edged nature of all the greatest Horrorcore: on the one hand, it’s just cartoonish enough to suspend shock and disgust, almost playful in its absurdity. On the other hand entirely, there’s the very real frustrations hiding behind that absurdity. Raised among gang activity in Sacramento, Hung himself was more of a peacekeeper: a member of the Crips, he was shot and wounded trying to break up a fight between a fellow gang member and a Blood.

Hence, there’s a real pathos to say, “Rest in Piss”. He’s suffered enough that there’s genuine iron in his voice when he wishes the worst on those who have done him the worst. Certainly not for the squeamish, but there’s very little like this anywhere else. – Chase McMullen

Carissa’s Weird – Songs About Leaving

[Sad Robot; 2002]

Songs About Leaving is a bittersweet album; bitter because its goodbye from Carissa’s Wierd – an already bleak band who made arguably their bleakest album yet as their sendoff –, and sweet because it holds onto some faint idea of hope, making the best of a bad situation through community or your own belief in yourself, even as you cry for help.

Bringing more chamber pop elements into the fold allowed the Seattle slowcorers to add some newfound grace to tearjerkers/self-loathers like “You Should Be Hated Here” and “Ignorant Piece of Shit”. Then, there are times when the misery is too great for anything but the trembling vocals of Jenn Champion and the pained strums of her guitar. These are personal stories of pain, but ones are applicable wherever, and whenever, you might be. – Brody Kenny

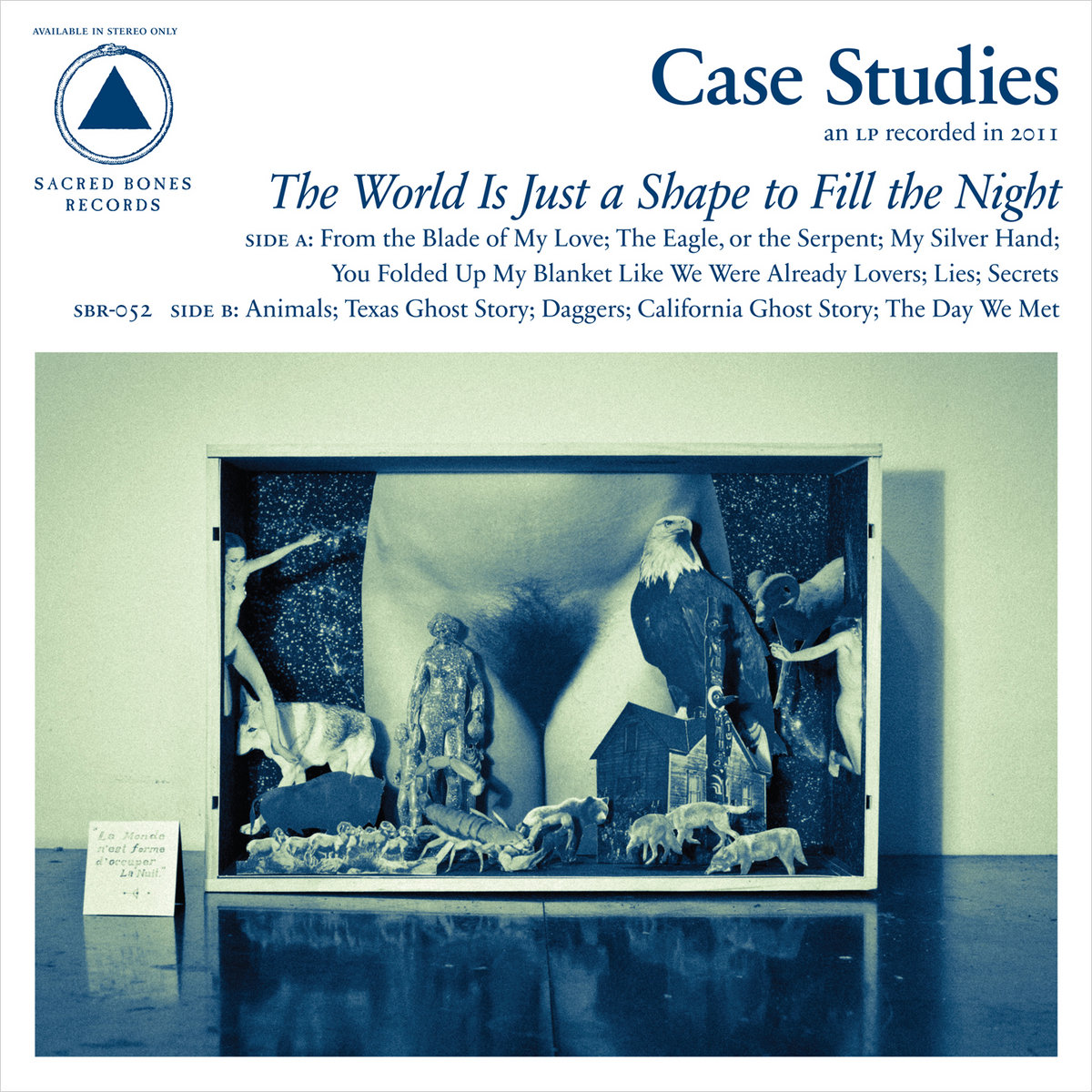

Case Studies – The World Is Just a Shape to Fill The Night

[Sacred Bones; 2011]

Jesse Lortz is no stranger to darkness, as his work as one half of the Duchess and the Duke lays testament to. But when he ventured out on his own under the Case Studies moniker, the darkness began to feel all the more real, like a tangible feeling of isolation and alienation from the surrounding world. The World Is Just A Shape To Fill The Night is a doomy-folk record, wrapped up in minor acoustic guitar chords, ghostly female vocals, and Lortz’s own beleaguered and demoralized voice. You might find streaks of light offering a moment of fresh air and respite through the glumness (“You Folded Up My Blanket Like We Were Already Lovers”), but it is soon swallowed up by the murky sullenness.

Lortz has a way of conjuring all the base, disturbed voices in his head into a call that sounds downright primal. On “Secrets” he snarls the album’s titular phrase as sitar notes percolate the air, while on “My Silver Hand” he turns what is an otherwise dreary but jangly post-break-up ballad into something worryingly sinister (“I’d like to still be in your bed / But I would settle for your life instead”). Across the album faces are threatened with daggers, wounded animals run scared, and children are told not to be afraid; the settings are dreary and dour, and through it all Lortz tries to reckon with himself (“This skin is just a mask I wear for now / so I can recognize my face”). The World is Lortz’s struggle moulded through ghost stories, feral nature, and pains from the past. If you’re happy for the darkness to take you a while, then you might just be surprised by how much is lurking in the shadows. – Ray Finlayson

Coil – The Ape Of Naples

[Threshold House; 2005]

By the time The Ape of Naples was released, Coil had long been been reduced to ashes. Actually, it had merely been a flicker for quite some time prior – where the leading duo of John Balance and Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson had once been a powerful arcane unit, Balance’s alcoholism had almost ruined their creativity. As Cosey Fanny Tutti retold in her autobiography, visiting the act after one of their shows had the green room divided by two, Balance slurring on one side while Sleazy would do his best to ignore the physical and spiritual decline of his former partner in life and art. In 2004, when Balance finally fell, presumably drunk, from his balcony, he left the world with a smashed head and plenty of unfinished material for Sleazy to comb through.

Thus, it’s no wonder The Ape of Naples ended up a eulogy of sorts, with a ghostly Balance serenading himself. And part of that makes sense, as Christopherson mused that only now could he decipher the album’s opening lines: “Does death come alone / Or with eager reinforcements?” Balance’s longing, present in the solemn prayer of “Cold Cell” and the drunken curses of “Tattooed Man”, and his unbridled anguish are now solved, were preserved in amber. At times, he sounds like David Bowie – others he almost recalls Jacques Brel. He has transcended to another plane, his voice graceful and, even when breaking, majestic, while Sleazy’s compositions feel contained and, in their queer post-industrial abstractions, like crystallized fossils of gothic jazz. – John Wohlmacher

The Cure – Faith

[Fiction; 1981]

A desolate album, made in the midst of the loss of close family members and heavy drug use, The Cure‘s Faith leans on the futility of existence for Robert Smith and bandmate Lol Tolhurst who were both raised as Catholics. The morose lyrical themes are accompanied by mechanical sounding drums, washes of keyboards, spiky post-punk guitars and Simon Gallup’s exquisitely gnarly bass which combine to create sombre, lacklustre and pained expressions of hurt, resistance and despair.

An album obsessed with death with tracks such as “The Funeral Party” focused on the mundane rituals that accompany grief and “The Drowning Man” highlighting the futility of it all, the album is the perfect example of Smith’s ability to really bludgeon the listener into a despairing sense of bleakness that isn’t present anywhere near as much across their back catalogue as people see to think.

The cathartic energy of “Doubt”, all post-punk riffs and mardy posturing, brings agency to the album where a sense of barren bewilderment at the lack of direction smothers the majority of the record. “Other Voices” is spectral, while “All Cats Are Grey” is majestic in its dark emptiness. The album’s closing line of “I went away alone / With nothing left but faith” comes across more like a rebuttal of religion than a vanquishing of the self-doubt that pervades the album as a whole. It’s a difficult act to sustain such a despairing atmosphere across a whole album, yet Faith is an absolute triumph of hopelessness, dejection and despair. – Todd Dedman

Current 93 – Imperium

[Maldoror; 1987]

Dave Tibet is one of the great seers of our time. An obscure figure, obsessed with esoteric British art and eschatological philosophies, he came up in the UK underground alongside such counter cultural figures as Steve Ignorant, Douglas P., and John Balance, often collaborating and releasing a series of haunting projects that saw him shout prophetic vulgarities over harrowing samples of choral music. An apocalyptic twist on Throbbing Gristle’s industrial formula, with Current 93 he proposed a nihilism shrouded in religious fervor which could only blossom during the nuclear anxiety of the Thatcher era. He finally caught this lightning storm in a bottle on Imperium, a strange, pulsating, visionary work that is both unique and thoroughly rooted within its historical context – the unheard crown jewel of mystical post-punk.

Divided in half, the first side of Imperium sees Tibet as a strange soothsayer who whispers over echoed melodies, medieval harps and grotesquely slowed down voices. It’s disquieting in its almost Lovecraftian otherness, especially when Tibet goes into a jolly tone to recount Christ’s demise during the fourth part. But it’s got nothing on the second half, likely the genesis of the neofolk genre. On the second half, in four songs that create the phrase ‘Be Locust Or Alone’, Current 93 become an apocalyptic version of PiL. The sample of a children’s toy on “Be”, the throbbing disco-bass on “Locust”, the hysteric chants on “Or”, and the agonized synthesizer on “Alone” could be right next to “Swan Lake” and “Careering” on Metal Box.

Meanwhile, Tibet’s lyrics are nothing short of dizzying in their solemnity. On “Or”, he cycles through punk prophecies of kings who ravage their land, finally crying like a madman “When I was a child in the belly of my mother / When I was a child in the palace of my father / Desolation!” and repeating “Take me to my Dead Christ!” On “Locust”, he opens with “What is all this love for / If we have to go out in the dark”, only to lose himself in references to the joys of “the locust summers”. In the end, Tibet reclines to the gaze of an old woman who ruminates on her failures and coming doom: “Whilst I thought I was climbing / I found myself descending.” Images of great wars and famine abound, characterizing an ashen Empire under the fist of a mad punk rock emperor. – John Wohlmacher

Damon Albarn – Everyday Robots

[Parlophone; 2014]

The frontman of Blur, Gorillaz, and The Good, The Bad & The Queen may not be the first artist that comes to mind when thinking of dark albums. However, darkness in music bears the same property as darkness when speaking about color — there are many different shades, all of which elicit different emotions. A keen listener to Damon Albarn can notice that even in his more upbeat songs there is an aura of melancholy at the very least. On his only solo album, Everyday Robots, the artist further explores this darkness that has followed his works since pretty much the emergence of Blur.

It’s quite varied — that is, it’s not a stream of depressing tracks one after the other; the track list is very well paced, spacing out the dark ones with some upbeat ones, such as “Mr. Tempo”. However, most of this album is dark. It sounds like everything Albarn has done before as well as none of it; it’s along the same aura he’s been following for a long time, it doesn’t come from nowhere. On the surface level, its lyrics are mostly to do with the weariness and anxiety of the exponentially digitized and faceless world. However, Albarn almost never leaves the literal meaning as the only layer of his songs. Beneath, there is a sense of loss, at least in the way I saw the album, but it is very ambiguous. It’s not loss of a specific person, for instance, it is a loss that cannot be conveyed directly, but it is something very universal. – Aleks Smirnov

Daughters – You Won’t Get What You Want

[Ipecac Recordings; 2018]

One of the most recent entries into the canon of post-hardcore, Daughters‘ latest album almost never came to be. Troubled by internal doubts and struggling with the harsh realities of being a lesser known act, the group had considered breaking up. After a lengthy hiatus, they finally agreed to give it a try, under the condition that the coming album would have to be of unprecedented proportions, a masterwork to justify the turmoil of recording and touring. The band demoed and recorded dozens of tracks, reportedly more than 70 song skeletons existed at a point, before they zeroed in on 10 of them. The material outdid any expectations. You Won’t Get What You Want quickly rose in stature and was almost immediately hailed as a classic. But it really comes as no surprise, as every element of the album demands attention.

There’s the haunting cover art from Jesse Draxler, both instantly familiar and totally alien, the ominous, machine-like beats and churning growls of opener “City Song” and Alexis Marshall’s flowering lyrics of urban decay: “This city is an empty glass / Words do nothing / No one sleeps.” It’s the cold, unflinching gaze of an unfeeling narrator usually only found in works of Cormac McCarthy or Hubert Selby Jr., cutting through his protagonists’ minds and hearts. And it delivers some of the greatest writing this century has seen so far, as evident on “Satan in the Wait”: “He can live without air for several days, he says / He says he knows things, this man, he says / He says he wouldn’t wait for the light or the dark to fade / He says you’ll want to move for the mouths of the damned elite.”

Musically, Nick Sadler’s metallic guitar sound stands out especially, at times battling Marshall’s agonized yelps, other times lending majesty to his struggles. While some take the record as the depiction of a forlorn city within a constantly nocturnal realm, it can also be interpreted as a savage takedown of capitalist America: as much as the narrator of “Guest House” shouts, beckons and exerts himself, there are no keys to the locked doors, no open windows. He could be a monstrous bogeyman, but what if he is but an agonized man, trying to make his way into a safe haven: “Who put a padlock on the cellar door? / Let me in… / I’ve been knocking / Let me in / Who bricked off the chimney? / I can’t hear you speak…” Is that who opens the door a naive victim or an understanding sibling? The question is nonsensical: there is no door. “In the air: shrieks. / The breath is long / And the fires are out. / The waters sit still.” – John Wohlmacher

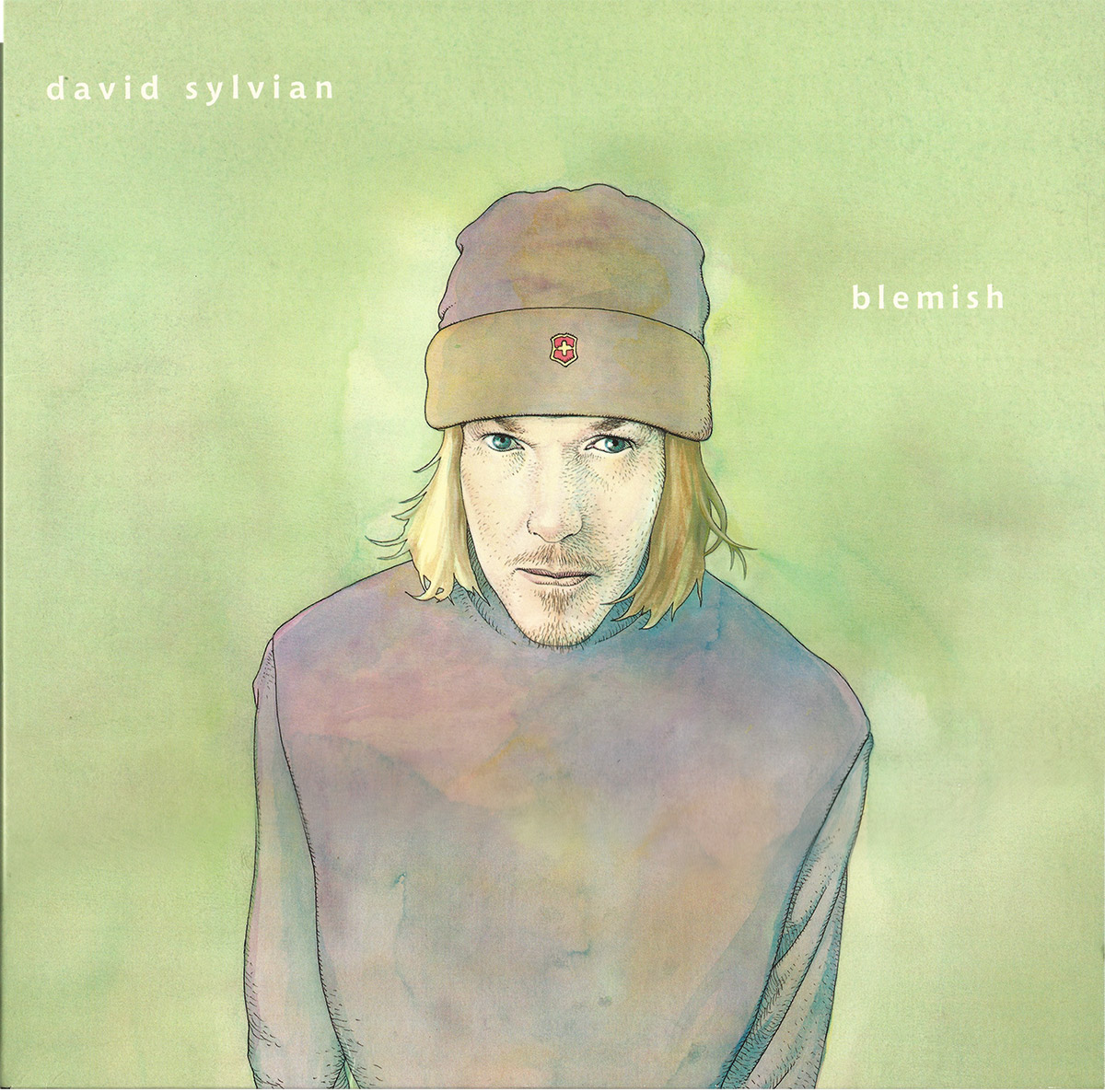

David Sylvian – Blemish

[Samadhisound; 2003]

Japan were the best effeminate futurists from the 80s, bar none. As the glamour and glitz of their output bled into arty introspection, the songwriting of lead singer David Sylvian came to the fore, and his solo work is marked by a persona of deep personal reflection with melancholic tendencies. His sixth solo album, Blemish, is his masterpiece.

The album opens with the title track, a near 14-minute trip of distended, unsettling noises and Sylvian’s exquisite baritone vocal. An album clearly documenting the breakdown of his marriage to Ingrid Chavez, the work cuts to the quick straight off the bat with the opening line “I fall outside of her / She doesn’t notice”. Obscure machines and obfuscated whirring noises come in and out of focus, the garbled thought processes of someone experiencing serious trauma. The pained personal lyrics are made even more powerful with the restrained and emotionless delivery – we are listening to the thoughts of a man totally bereft of a spark, battered by circumstance yet mantra-like in the delivery of home truths and clichés.

The album is strewn with disconsolate rejection, and the hatred borne from being spurned and convincing everyone, but mostly yourself, that you hated her before she came to hate you. Recurring images of a bed are revisited across a number of the tracks, a space of exquisite intimacy and depressing loneliness.

The closing “A Fire in the Forest” is a plea for mindful peace and its place at the end of the album suggests that the cathartic experience of recording this work may well have paid off for Sylvian. Good for him, obviously, but the emotional scars left as you weave your own way out of the listening journey will resonate for some time. – Todd Dedman

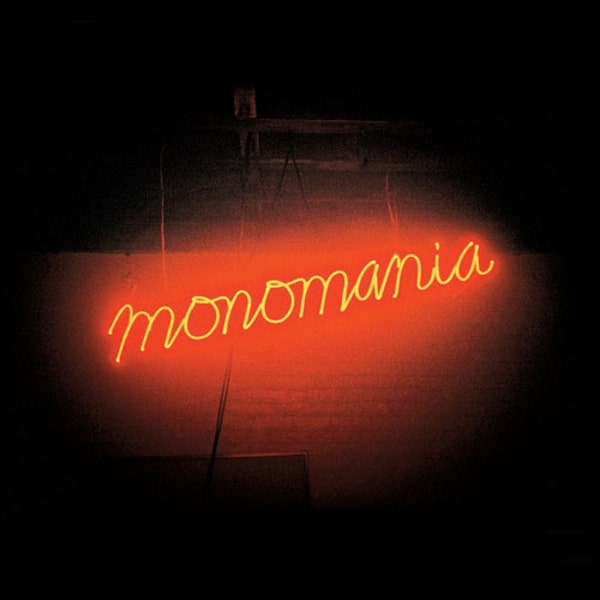

Deerhunter – Monomania

[4AD; 2013]

In retrospect, Deerhunter‘s Monomania wasn’t viewed as that dark of an album upon release. It was a harsh pivot from the dreamy jangle pop of Halcyon Digest, while the reverb linings of the shoegaze masterpiece Microcastle were long gone – but beyond the sonic shifts, Monomania may be the darkest moment in Bradford Cox’s life fully on display for our consumption.

The garage popper “Neon Junkyard” is a misleading opener. As the album progresses through the chaotic “Leather Jacket II”, it becomes apparent that Cox is in a much darker place than he was before, even on the somewhat morose beauty of Halcyon Digest. He quips on masculinity, takes a dagger to genre classifications, sits uncomfortably in his own obsessions, and transforms the personality once thought to be delicate and vulnerable into a burnt-edged Stepford Wife. The most riveting instances on Monomania come from Cox’s brutal honesty – “T.H.M.” has been stated by Cox to be about his dead brother, and it’s the album’s darkest point. The imagery of the band around the release of the album was also darker; black and white photos with all members dressed like thrift store bandits, which felt like some kind of homemade Clockwork Orange reinterpretation. And lets not forget the iconic bandaged and bewigged performance of the title track on Fallon.

All these years later, we can trace the departure of the late Josh Fauver to some of this darkness. A core band member, and the man responsible for some of their iconic bass lines including “Nothing Ever Happened”, Fauver’s departure left room for forced transition. Cox has dwelled on the idea that the band should have ended after Fauver left, but if that were the case we’d never get to hear the beautifully deranged psyche of an individual who consistently reinvented rock in his own image. Monomania is the Deerhunter record that stands out the most these days as it’s not like anything else by the band, and therefore represents Cox at the height of his powers – extremely low and seeking catharsis. – Tim Sentz

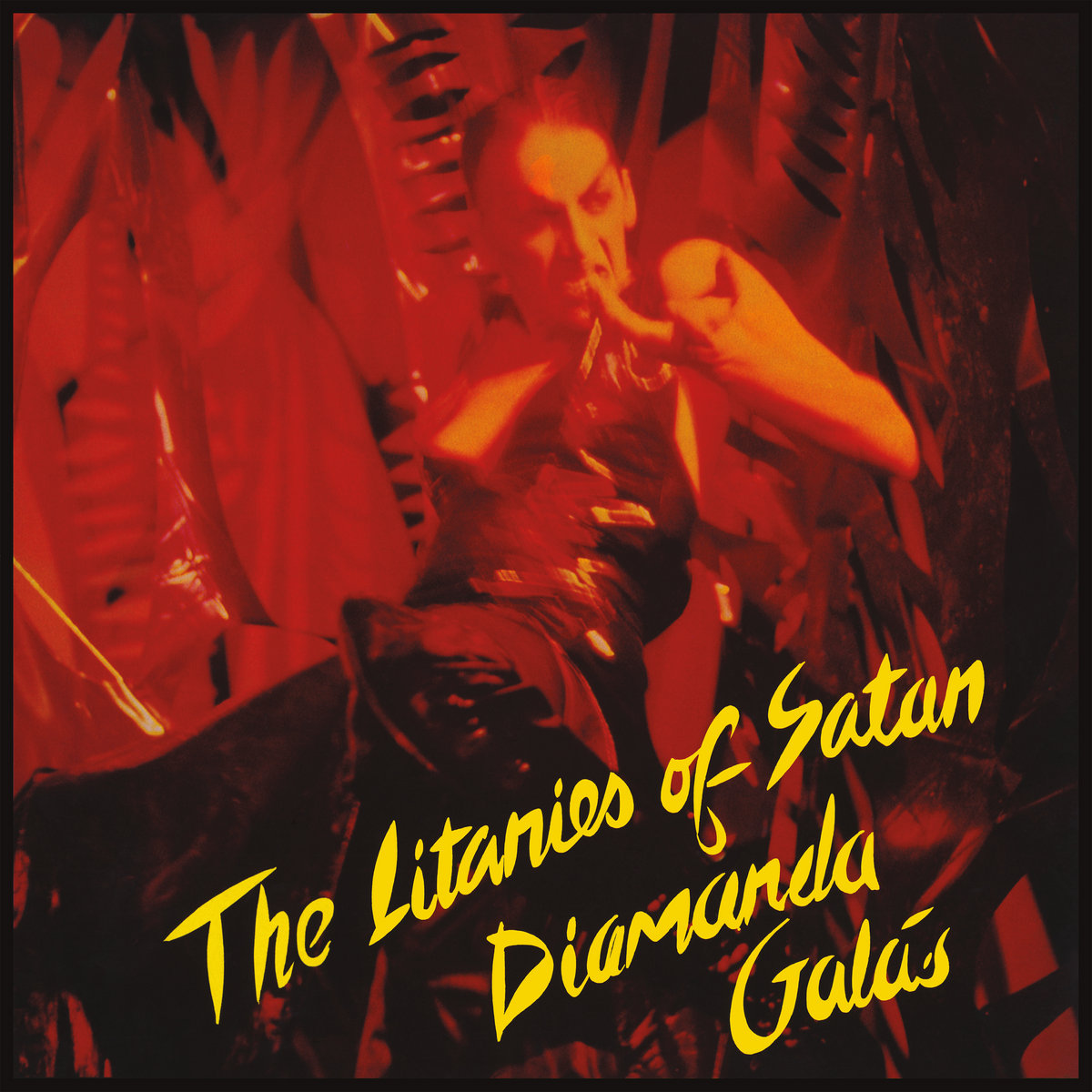

Diamanda Galás – The Litanies of Satan

[Y Records; 1982]

Diamanda Galás‘ first album is an exercise in extremity. It is a 30-minute art piece, a work of such experimental intensity that it is really more of an ‘experience’ than something as humdrum as a ‘listen’.

The title track, based on text by Baudelaire, sets the scene with Galás’ guttural wails, screams, and incantations. She is raspy, throaty, shrieking, and her voice crackles with electricity. The second side, “Wild Women with Steak Knives”, takes it even further into the abyss. The effect of the recording, Galás often using two microphones, is to give her voice an echoey, cavernous brutality that only enhances the strange darkness inherent in her performance and the text.

The Litanies of Satan is the sound of torment, of the limits of human endurance, of the darkness of hell. – Matthew Barton

Earl Sweatshirt – I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside

[Tan Cressida/Columbia; 2015]

“And I don’t know who house to call home lately / I hope my phone break, let it ring,” should tell you all you need to know about Earl Sweatshirt’s contemplative second album I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside. Often overlooked due to his excellent debut Doris and stellar third record Some Rap Songs, Earl’s middle child album bridges the gap between both, and surpasses them in several ways. At the time of its release, Earl was well on his way to carving out his uniqueness in the Odd Future roster, and this album created a new trajectory for him thanks to his superpower – he possesses the unfortunate gift of being emotionally mature.

I Don’t Like Shit is summed up pretty perfectly with “Grief”. The then-21-year-old Earl’s odyssey with himself takes the reins and he rides it through a bitter cold series of self-aggrandizing insults. “I don’t act hard, I’m a hard act to follow,” he says with a degree of certainty, but also reservation. Earl’s writing from a darker place than most, and he even says it “I ain’t been outside in a minute / I been living what I wrote.” Earl’s on his own island amongst his Odd Future brethren – deeper, darker, and totally comfortable with his isolation.

I Don’t Like Shit is a young rapper processing his mental anguish and attempting to come out the other side.It is a 30-minute snapshot of youthful voices demanding an ear to listen without speaking. Whether he’s yelling into a void is immaterial, Sweatshirt’s pilgrimage into his psyche is a victory, even if its weight is overwhelming at times. – Tim Sentz

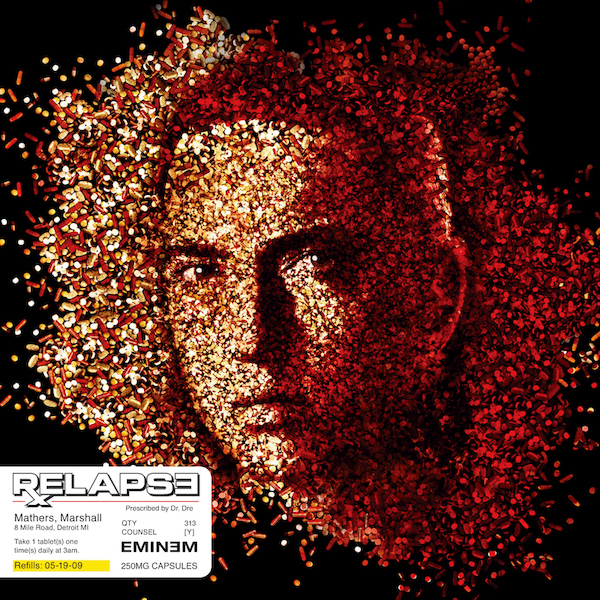

Eminem – Relapse

[Aftermath/Shady/Interscope; 2009]

It’s not without reason that this thing greatly impacted Odd Future: when Tyler, the Creator counts it among his all time favorites, well, it’s not hard to tell why. Recovering from addiction and still spiraling from the crushing loss of his lifelong best friend, Proof, Marshall Mathers hesitantly reentered the studio with one goal in mind: to squeeze out every damn bit of bile in his overloaded system. Retreating into horrorcore made far more sense than his wider fanbase appreciated, it was a Detroit go to, after all, a history he was steeped in. Sure, Eminem had dabbled in murder fantasies before, but (the ultra-intense “Kim” aside) always with a knowing wink.

There’s very little smirking to be found on Relapse. These are songs of mental decay, a shockingly bleak statement from the biggest star in rap that consumers at large simply failed to understand. It’s a shame: I’ve long argued this was, in some ways, Mathers’ Pinkerton. A deeply personal look into flaws and his very heart of darkness, the tepid reception it received seemingly broke his faith in his own ears.

He’s made some solid, underrated statements since, but nothing that nears the circus of the gross that was the masterful Relapse. The reappraisal it’s received over the years is seemingly too little, too late. Just compare the limp murder fantasy “Black Magic” off his most recent album to, say, “Stay Wide Awake”. The fervor was undeniable to the point of being frightening. This was unshakable grief masquerading as a seething, diabolical mess, as shattering (and shattered) as its limping creator.

His vision had perhaps never been so laser-focused. Hell, speaking on the harrowing “Same Song & Dance”, Mathers revealed he simply wanted to see just how disgusting he could get over a bass-heavy, even gorgeous Dre beat (I mean: “Girl, shake that ass, you ain’t never gonna break that glass / That windshield’s too strong for you”) and see if people would still dance to it. So, did they? You already know the answer. Relapse reveals just as much about us, and what we’re willing to engage with, as it does its creator. – Chase McMullen

Emma Ruth Rundle & Thou – May Our Chambers Be Full

[Sacred Bones; 2020]

On 2020’s May Our Chambers Be Full, the heavily textured folk of Emma Ruth Rundle meets the sludgy, apocalyptic sonics of Thou; Rundle’s woundedly angelic voice mixes with Bryan Funck’s hellish growl. “Monolith” features an alloy of riff-y guitars, pounding drums, and a punching bass, Rundle’s voice tossed on the tumultuous soundscape. When Funck’s voice joins Rundle’s, the result is a chorus of suffering, two damned angels delivering their imprecatory anthem.

On “Ancestral Recall”, Funck’s sepulchral voice saws through relentless instrumentation, a vengeful demon howling from the depths. Following the song’s relatively austere bridge, Rundle joins Funk, again creating a spellbindingly ominous vocal blend, each singer exuding a sense of profound and palpable anguish – Rundle assertive yet sirenic, Funck purely aggressive and defiantly unremorseful.

“Into Being” opens with Rundle singing, “All alone / All alive / Undefined.” Funck then joins and the two sing together: “Tethered, we will never know the river of a real life.” The feeling evoked is one of existential and karmic despondence. Rundle and Funck are Milton’s doomed angels venting sorrow and indignation while a troupe of other exiled beings offers primally rhythmic and malevolently atmospheric instrumentation, love and hate inextricably and toxically mixed. May Our Chambers Be Full exudes irredeemable angst while offering fleeting moments of transcendent rapture, a magically disturbing sequence. – John Amen

Listen along with our Darkest Albums Spotify playlist