The latter half of the 1960s is part and parcel of American folklore. Freedom, love, the hype and iconography of flower power. Lest we forget, though, Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965, MLK in 1967, and Bobby Kennedy in 1968, which essentially marked the irrevocable decline of progressive politics in the US. Nixon was subsequently elected president, prompting the post-Civil Rights boomerang years, a time which has much in common with our current era.

While many consider Woodstock the equivalent of a lysergic peak, it might be more accurate to dub it the come-down or crash; those chimeric days at Max Yasgur’s farm were, in hindsight, more like a beautiful funeral, the end of an epoch that, despite its enshrinement in the contemporary imagination, was short-lived, undercut before it had a chance to fully blossom.

Marking significant sociopolitical shifts, the mid-late 1960s also functioned as a big bang in the musical domain, all but eclipsing a precursory span of pure pop, often associated with the 1950s but which commenced way before that, culminating, perhaps, with Motown and Philles Records, surf rock, the glamorized British invasion. There’s nothing like those celestial melodies courtesy of The Supremes, The Four Tops, The Ronettes, The Crystals. Early Beach Boys, Beatles, Stones. The bubbly proto-punk of The Kinks. Approximately 6 decades later, these precedents still exert an influence, reminding us of what’s possible in the pop domain.

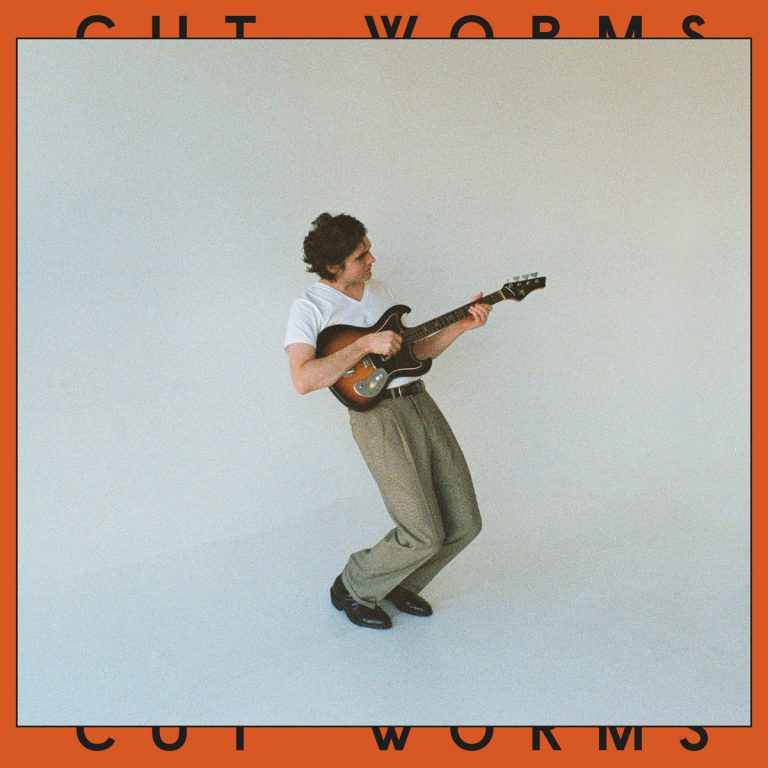

Among devotees of the early 1960s playbook, one of the more loyal is Max Clarke, a.k.a. Cut Worms. Building on the reconfigurations displayed on 2018’s Hollow Ground and 2020’s Nobody Lives Here Anymore, Clarke releases his third and self-titled LP. To say the Brooklyn-based songsmith pens catchy tunes would be an understatement. On opening track “Don’t Fade Out”, he drapes an irresistible melody (you’ll be humming this chorus for days!) over chugging guitars and snappy drums. “When it gets worse all the while / how can I just take it and smile?” he muses on track two, stirring innocence and disillusion, venting the hardships of life, though via hooks that would flood the darkest dungeon with golden light.

This is pop’s gift: not denial, but recalibration. Much as a comedian crafts his content in the aftermath of tragedy, pointing out how laughably predictable humans are, Clarke and his predecessors embrace optimism despite the reality of Dylan’s “long black cloud” and counter to Kendrick Lamar’s hard-boiled mantra (“protect yourself / trust nobody”). Life can end, pop tells us, in triumph rather than defeat.

“I’ll Never Make It” features a jangly guitar that conjures clean garages and BBC George Harrison. The slower “Is It Magic?” aspires to gestalts a la Merriweather Post Pavilion but lands more squarely in Brian Wilson-esque mixes, channeling the harmonies of The Everly Brothers and Lennon/McCartney. “Living Inside” is built around a bouncy rhythm and sumptuous melody. “When the leaves all start to change and the air is cool / and I’m riding on the bus going back to school”, Clarke reminisces, recalling Big Star’s glorious “Thirteen”. On closer “Too Bad”, he reflects, relatively seriously, on cognitive dissonance and, ultimately, death, the ineluctable yang to pop’s yin.

Pop is archetypal for its seductive properties, how an elementary lyric and transportive tune can deliver a listener from their burdens, serving as balm for any number of griefs. While Clarke remains tethered to his sources, he still manages to flap his way toward the sun. In this version of the myth, his wings hold up, his father congratulates him, and the gods give him a brief yet sincere ovation.