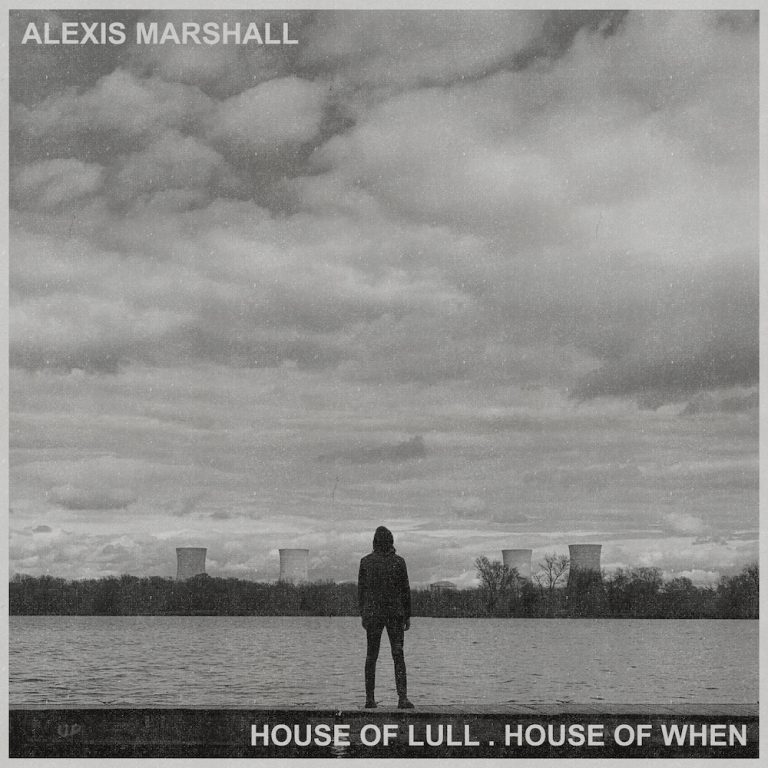

In the Psalms, the mighty King David was in constant emotional tumult as he wavered between reverence toward God and a desperate yearning to be rescued from the depressive thoughts that overwhelmed him. Despite falling under the dark veil, David continued his prayers, and God’s promises kept him grounded in some semblance of reality, whereas his lavish power and wealth could not. But what happens when God doesn’t answer back? This question is explored with brutal honesty on House of Lull . House of When, the debut solo project from Alexis Marshall, brilliant vocalist of noise rock behemoths Daughters.

While resolve is suggested when it comes to the story of David, not a single cloud parts for Marshall throughout this record. Granted, there wasn’t much hope for him to cling to; as he warned us on debut single from last year “Nature In Three Movements”, that he “couldn’t be left alone” – and, after experiencing the bludgeoning song, one could easily hear why.

One year later, here we are with a collection of tracks in a similarly bleak vein, as Marshall finds himself in the same boat, incessantly repeating, recycling, and retreating into the darkness that has overwhelmed him in years past.

Listening to the wildly ferocious vocalist mangle the airwaves with his desperate cries for help could convince a casual listener that he’s gone insane. But that’s not the case here. Rather, Marshall is simply stuck in a haunted milieu, where images of the past flash before his tired eyes, his depravity inescapable through every hour of the day. Through an onslaught of paranoid abstractions and sarcastic reckonings with God, Marshall proves to be an unhinged poet, stuck but actively seeking to secure himself to what is true and real. Naturally, the attempts are agonizing, terrifying, and, unfortunately, fruitless, as fear of relapsing into addiction and memories of physical and mental trauma shackle him to the bedside, fully awake but only slightly aware of the remnants of reality that surround him.

“The past is like an anchor,” Marshall admits on album opener “Drink From The Ocean, Nothing Can Harm You”. It’s an admission of a lost battle after the rabid refrain of “can’t be weighted down” from “Nature in Three Movements”. He continues on “Drink From The Ocean…”, “You dangle your foot over the bed,” with hopes of gaining the slightest sense of what is real amidst his inner toil. This is an act of faith, or even surrender: “Come drift across the rooftops. I am here./ Come glide across the rooftops. I am here.”

Still, no one, not even God, hears or sees his cry for help.

All he’s left with at this point is the option to retreat into his cavernous shell, where scary thoughts go bump in the night. Billowed by ghostly waves of strings, Marshall’s words come across as desperate — like David in the psalms who, despite his vices, sought to be saved when he knew he was likely damned for eternity. Marshall’s damnation is his own head, clouded by the past. Thus, this hellish descent into madness snowballs dangerously into paranoia.

On lead single “Hounds In The Abyss”, Marshall suspects an unwanted visitor in his house, a delusion that eggs on his ongoing anguish while threatening to pull him into whatever festering memory he is feverishly trying to avoid. “Are you the one throwing rocks at my window all night?” Marshall asks dementedly on the track, “Are you the one standing outside my house when I’m alone?” But before this stranger is able to break down the door, Marshall swings it open, and what does he see? Himself, of course.

Standing at the doorway, Marshall’s looming antagonistic ‘other’ berates him with insults upon insults on the following track “It Just Doesn’t Feel Good Anymore”. Quickly, his paranoia becomes self-doubt and self-hatred: “Don’t get up / Don’t go out / Don’t touch anything / Don’t touch anyone / Don’t look at anyone”, he demands of himself on the track. “You have obligations… Meet your obligations.”

Marshall’s words may not sound caustic on paper, but the sheer tone of his voice, magnified by percussive hostility and scorching horn squeals, makes them so. It’s a manic instrument of fire and brimstone, one that wrenches the door just a tad bit wider for listeners to try and understand more about his fears and insecurities. Though they’re never clearly identified, he keeps these thoughts and sentiments chained to him throughout the terrifying show, albeit with some slack to keep his audience intimidated and at bay. Now, this is not supposed to be an Alexis Marshall aural sideshow about trauma, nor is it a petting zoo of demons to gawk at; this is a vivid glimpse into the type of monotony and uncertainty that has overwhelmed the rabid artist as of late.

Still, the ferocity of House of Lull. House of When is a marvel rooted in the purposeful attention given to its unique percussive elements. Einstürzende Neubauten in spirit, the record’s deafening percussion tethers Marshall to reality as he traverses his own dreary nightmares. From chains dragging across the floor to coins dropping from above, the sound of two objects colliding serve as Marshall’s dream totem. The effect of crashing cymbals and pulverizing bass drum, among other striking tactile objects, underlines the impactful use of repetition on the album, making Marshall’s fixation on recycling simple words and phrases even more potent. The poet in him is on full display. Some say insanity is doing the same thing over and over while expecting different results. Well, when you listen to tracks like “They Can Lie There Forever”, where Marshall ominously screams “Deer in the headlights” nonstop, intermixed with a second repetition of “I was only passing through”, a tormented psyche does materialize.

As we struggle to keep our heads above the storming waters that swish, swash, and tear through Marshall, listeners also pick up on a feeling of distrust and betrayal that he feels towards life or some kind of higher power. On the apocalyptic twin tracks “Youth as Religion.” and “Religion as Leader”, Marshall probes into the idea that God could find us in desperate and desolate places where they are least expected. He begins both songs with a despondent tone, laying out his own heart and state of mind: “God finds you in such places / Chaste at the bottom of a well / Foot upon the frame / Fever at the bedside / Desperate from a head wound.” He utters these words with sneering irony, highlighting that God cannot see Marshall as he’s shrouded by the hopelessness that plagues him, then concludes, “The night does not begin / So, the night cannot end.” Marshall’s scoffing doubt bleeds into the remainder of the album and is most obvious on “Open Mouth” where he furiously questions: “Has the rapture come? / Has the Tuesday morning come?”

In 2021, there may be no more effectively desolate album than House of Lull . House of When. It’s an intense and harrowing listen, absolutely worthwhile, yet not for the faint of heart. There’s simply no air to breathe, nor the faintest glimmer of light to follow. For 42 minutes, listeners will feel like they’re being dragged into the deepest depths of the ocean by some amorphous and unknown sea creature. There’s no hope, and the only way to escape its grips is to hit pause. Sometimes, albums this dismal are too difficult to bear — House of Lull . House of When is a textbook case. Do approach this record with a sound mind and heart, appreciate the lengths to which he pushed himself to make it, but do not indulge too much with admiration.