In the early to mid-2000s, the flag of the freak folk scene was flying. Like — gale force, tree branches falling onto fences, stay-indoors-until-further-notice — flying. Drawing partially on and blending psychedelic and folk styles from the 60s and 70s, the time of the freak folk genre — coinciding with the New Weird America movement, sometimes interchangeably — was a curious time in modern indie folk music. It represented a sort of new musical counterculture, but what exactly it was countering is a little unclear. Perhaps the tidiness of new, shiny recordings? Maybe singer-songwriters who aligned more closely with pop making it bigger on the airwaves. But overall, it feels a little bit like a misnomer; it’s a label that alludes to a sense of “weirdness”, but in a way that, in retrospect, feels a touch more othering, a little more isolating, than anything else.

Getting deeper into it, the striations appear. On the stripped down folkier side, we had people like Devendra Banhart, Faun Fables, and Diane Cluck. On the trippier and more experimental side, we had acts like CocoRosie, Animal Collective and Rio En Medio. Some people were often lumped into the scene who either wound up quickly departing from it or never really belonged in that conversation in the first place, like The Dodos or Iron & Wine or Alela Diane — acts that felt like folk or folk-adjacent, but whose placement within this sphere felt decidedly incorrect.

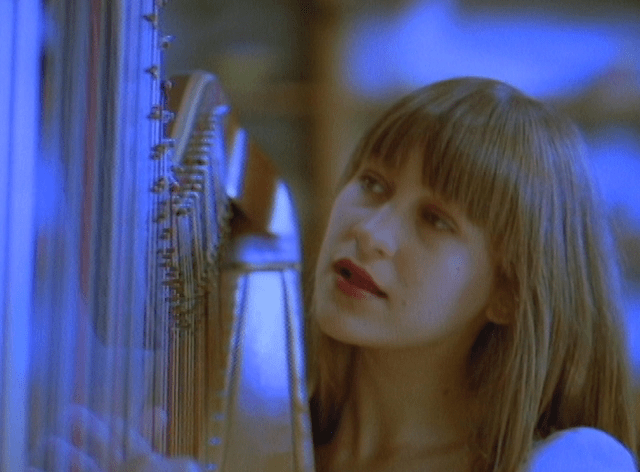

Banhart, especially, seemed to be at the forefront of freak folk, and is one of the few on the list whose newest music could still roughly be slung under that umbrella (even though the umbrella has shifted a bit in the past two decades). But one of the other artists that meteorically rose out of the freak folk scene was harpist, singer, and songwriter Joanna Newsom.

Now, Newsom hasn’t released an album since 2015’s Divers, and by then her work felt quite a ways away from the freak folk sounds she was filed under when she debuted in 2002. Even so, she never truly felt at home in that camp; her music was a kind of odd, left-of-center, and maybe that was enough. Her first couple EPs laid out her M.O. pretty well: flowing melodies, deeply verbose and poetic lyricism, beautiful and complex harp, and — her most divisive quality — that immediately distinct voice.

Newsom’s voice on those early EPs (2002’s Walnut Whales, and 2003’s Yarn and Glue, released when she was only 20 and 21 years old) is a unique sonic experience, and they are by far the most austere work of her career. Her voice was wildly untrained and she hadn’t figured out how best to use it yet; she hadn’t wrangled that incredibly versatile but gently shocking instrument, with its distinct tone and reaching, yipping caws. Her voice in those early years was called all sorts of things, including being compared to either a very old woman or a very young child. It was warbling, creaky, and prone to squeaking as it shot to its higher registers. It was unlike anything I, and many others, had heard up to that point. It made those EPs a very specific, but at times brittle and difficult, listen.

(It is worth noting that her voice changed quite audibly as the years went by. At one point, she even underwent surgery for vocal polyps, which changed it more. By the time we got to Divers, her voice sounded like a whole different version of itself from those early years, which is undoubtedly due to figuring out how best to use it, as well as age, of course.)

A year later, in 2004, she released her first full-length album, The Milk-Eyed Mender, and everything started changing. Those early EPs were self-released and sold at shows, but luckily, one of them found its way to Will Oldham — aka Bonnie “Prince” Billy. Oldham liked what he heard, and when he passed it over to his label Drag City (themselves quite the purveyors of a myriad of musicians whose work is “freaky” and “weird”), she was signed and ready to release an album.

On 23 March 2004, Drag City put out The Milk-Eyed Mender. Right away, the rough-hewn edges of her sound from the EPs felt softened, ever so slightly. The recording was clearer, spacious, with a nice touch of reverb and sense of place. Moreover, her voice sounded stronger, fuller, older (despite being recorded so soon after the EPs). It was still a strange and potentially off-putting voice to some, retaining its whimsical, unpredictable way with melody and occasionally abrasive high notes, but it was also warmer and less out-in-the-ether. She wasn’t whipping around in the wind as much anymore, instead hovering closer to the ground.

Still, it wasn’t like she suddenly became some mainstream pop success. Newsom’s music remained singular, idiosyncratic, sometimes divisive; still, she had quickly and firmly planted her hooks in music listeners.

When I first heard her work, it was through a MySpace media player. I had seen a review of her second album (2006’s Ys), and I must have clicked a link to her — or someone’s, I’m not sure anymore — MySpace page within it. “Bridges & Balloons” slowly faded in, that gently bubbling harp progression ushering me into her world, placid and instantly transportive. And then she started singing.

I wasn’t prepared. I had read the review of Ys, and it sounded like it was downright magical (and, of course, it is magical, which I hadn’t figured out yet), and then I had looked up some other scores it was getting. Huge praise was flowing her way. But the first song I heard, the first one to automatically cue up for me on that dreg of social media’s yesteryear, was from her first album, and I was not ready.

Her voice came out of my speakers and I was immediately in a panic. What was this? This is what is getting all this praise? Mind you — I was 13 years old, just beginning to really find out what I liked in music, and folky singer-songwriter material was already very much my bag. And the harp is such an indisputably pretty instrument that I felt, after seeing various reviews, that I would definitely like this. I was also very into reading and writing, and it sounded from these writers’ accounts that Newsom was a linguistic specialist, a wunderkind of verbiage, a master with the pen.

And, to be clear, she is — and always has been — but my adolescent brain could not even compute the depth of her poetry, the knots of her intricate wordplay, the graduate course-style Lexile level. I was stuck on the voice. It was (and still is to an extent) absolutely an acquired taste, and I’m sure even Newsom would admit that she doesn’t sound like every (or any) pop songstress or folk singer. Her closest analogues vocally, at that point, were probably people like Diane Cluck or Josephine Foster. It was a voice that, quite frankly, turned me away.

But something — some ineffable quality I couldn’t pin — kept me coming back.

I went back a few times, trying to find what it was about “Bridges & Balloons” that held my interest, awestruck as I was. I was convinced I’d like it if I just gave it time. Slowly, and for reasons I still can’t quite explain, it started to grow on me. The voice that once sounded aggressively strange and creaky and unapproachable was becoming rich, compelling, and beautiful. And from there, after spending similar time with “The Book of Right-On” and “Clam, Crab, Cockle, Cowrie” — other songs on that MySpace page — I continued to bypass Ys for the time being (mostly because of its gargantuan song lengths), and found a stream or download of her whole debut album, and dove in.

The Milk-Eyed Mender is a wonder of a debut. Very few other musicians in the singer-songwriter realm arrive with such a distinctive and fully-formed sense of identity and voice (and I mean that in all senses of the word). Newsom’s singing gave her a unique ability to weave a melody of indelible grace and unpredictable direction, sometimes squealing or howling, sometimes careening up and down across her range. And yet, many other times, settling into a soothing and smooth quieter end. Despite the impossibly strange timbre of her singing, Newsom wielded it in some impressively subtle and deft ways, wrangling humor and pathos and wide-eyed wonder out of its wiry shapes.

Take the opener: the aforementioned “Bridges & Balloons”. In retrospect, it’s truly the best welcome into Newsom’s world. Starting with a slowly-blooming harp progression, Newsom eventually opens with her gentle and unforgettable olive branch to the listener: “We sailed away on a winter’s day.” It’s the start of a storybook, the inciting incident of the next near-hour of music, welcoming the listener in. Sit down a while and listen, it invites us. What follows is a story of sailing on dirigibles, malleable fates, calm canaries growing irritable. It’s not exactly an immediately discernible narrative, but it does show her cards early and fully. Natural imagery, tricky wordplay, figurative language, dense vocabulary, literary allusions (a passing reference to “Cair Paravel” from the Narnia books) — it’s all there, and then, in a graceful slur of harp, the song closes out.

“Sprout and the Bean”, the only single from the album, comes next, and changes course while retaining basically the same elements. This is where Newsom’s absolute mastery of her harp comes into full focus. What starts a simple waltz in ¾ time becomes ever more complicated by interlocking plucks from her right hand. It almost feels like her right hand is playing a completely different time signature, only meeting up with her left hand every so often. This technique is something Newsom returns to over the album and across her career — its inspiration largely comes from a mix of classical, African, and South American harp music, with its focus on texture and syncopation — and it is deployed beautifully here. She’s a sly commander of rhythm.

“Sprout and the Bean” also contains another trick that will come back later in the album: the layering of her voice. In the chorus, we get a school of Joannas singing “Should we go outside!?” in a wailing shout. The effect is jarring, jostling us out of the lull of the song’s pristine verses. Perhaps by design, we are woken up with an invitation to go out in the world, break bread, and get to know each other. The tactic repeats later on the ending bridge of “Peach, Plum, Pear”, and while it’s equally jarring, by then, we’re accustomed.

“Peach, Plum, Pear” is actually a bit of an outlier here, despite its popularity with fans. The song has long been a fan favorite, and has become the most-performed song in Newsom’s catalog, changing in stylings, tempos, and sounds across its many years being played onstage. In its original state on Walnut Whales, it was an electric piano ballad, with one of her most mewling and childlike vocal performances (it almost sounds like a character from Rugrats moonlighted as a singer). On The Milk-Eyed Mender, it’s set atop a forceful harpsichord progression. The sonic texture of the harpsichord is, admittedly, a little grating, but the songwriting is strong enough to withstand the tempest of keys.

Where some of Newsom’s lyrics reach for the ether of the natural world or sail through imagistic poetry, “Peach, Plum, Pear” has some of her most direct. “Am I so dear? Do I run rare?” our narrator asks herself, after what is essentially a meet-cute at a store (“We speak at the store / I’m a sensitive bore / You seem markedly more / And I’m oozing surprise”). It’s a sweet song of a crush, but as the doubts creep in and complicate our narrator’s feelings, the vocals layer up and mirror the inner turmoil. It’s a canny bit of studio trickery that actually furthers the theme of the song, sticking out sorely but not unjustifiably.

There are a couple other outliers here that disrupt — mostly in a good way — the framework initially laid out in its first four songs. “Inflammatory Writ” is a short, bright, bleating piece of jaunty piano art-pop. “This Side of the Blue” is a slow motion ballad set upon a fuzzy, warm electric piano. On this one, images of birds passing, of someone eating lemons, forests, moons, and water all pass by in a blissful blur. Named characters pop up — Svetlana, Gabriel, Jamie — as our narrator comes to the conclusion that, at the end of the day, we are all just doing our best. But despite the potentially bland universality of its themes, the song is so rich with imagery and allusion. A reference to Albert Camus here; a mention of the San Francisco Embarcadero there; a description of migrating birds that feels like seeing birds for the first time (“Across the sky-sheet, the impossible birds / In a steady, illiterate movement homewards”). “This Side of the Blue” represents Newsom’s gift of transmuting the ordinary into the extraordinary.

A final outlier is found in the penultimate track, a piano-based rendition of the traditional folk song “Three Little Babes”. It’s by far the weakest track in the tracklist, and it’s not just because it’s the only one Newsom didn’t write — she has included covers on other projects, including the traditional-by-way-of-Karen Dalton number “Same Old Man” on Divers. It’s because of how vividly it sticks out. It’s arguably the only song on The Milk-Eyed Mender that sounds like it could be from those same early days of the EPs. Obviously, not a ton of time passed between the creation of the EPs and the debut album, but even in that short time, her voice matured quite noticeably and sounded warmer and more controlled, and on “Three Little Babes”, it doesn’t really sound as strong or refined as it does elsewhere. And that might not be the biggest issue if it wasn’t for a melody that’s irritating and repetitive.

It’s a small quibble, of course, when there is so much bountiful beauty to be found across the other 11 tracks. Newsom continues her tracing of everyday life and everyday woes on the brilliant and touching “Sadie”, which was written in tribute to a lost pet (“So dig up your bones / Exhume your pinecone, Sadie” go the heart-tugging final lines). You’d possibly miss that theme amidst all the symbolism and images of sewing hoops, aching refrains about what’s she’s lost and what she’s losing, as well as the eponymous milk-eyed mender.

Elsewhere, she laments the difficulty of writing with passion and intent on “Inflammatory Writ”. She remarks on the glories of lying down to take a good sleep under glorious stars on “Cassiopeia”. She compares herself to being so enervated as to seem dead while waiting for someone to return on “Sprout and the Bean”. And this is all rendered in poetic writing so deft and entrancing that even the smallest and most quotidian of life’s details feels grand — and, furthermore, even the songs whose meanings are a little more out of reach feel utterly transfixing all the same.

Take a song like “”En Gallop””. After an extended, gorgeous harp intro, Newsom breaks in about a place that’s “damp and ghostly”, with “palaces and storm clouds” and “rough, straggly sage.” It’s a study of a place, and at first that seems to be all it is — a sung landscape portrait. But little hints of unease creep in around the edges of the peaceful scene. There’s a something that she doesn’t know (“It beats me!”) and is nagging at her mind; there’s a contention with the “laws of property” and the “free economy”; at one point, she even pleads to an unknown force “You could’ve told me before.”

Finally, a warning, writ in one of Newsom’s finest and most economical verses:

Never get so attached to a poem

You forget truth that lacks lyricism

Never draw so close to the heat

That you forget that you must eat, oh!

What is she warning us of? Feeling too close to an artist? Not to get so close to a piece of work that we forget why we’re making it in the first place? Is it about us? Is it about others? It’s wonderfully ambiguous, left unclear in the ether as that final “oh!” ejects in a soft warble, before the stunning outro leads us out over almost two minutes of interlocking webs of harp. (It might be of interest to note here that the original version on Walnut Whales punctuated one of its verses with sharp ejections of “Bitch!” after each line. Thankfully, those were excised for the album version.)

There are moments of gorgeous ambiguity all over The Milk-Eyed Mender. On “Swansea” (which, in a gobsmacking and bewildering reveal, Newsom told crowds on her most recent tour was instrumentally composed when she was only 16 or 17 years old) she sings at first to someone who she wants to be near (“If you want to come on down…”). But then, the middle section changes chords and rhythm, and we’re greeted by lines as blissfully odd as “And all these beastly bungalows / stare, distend, like endless toads” and “’Till we are wracked with rheum / by roads, by songs entombed.” We even get one of her earliest horticultural lists (a tactic she would repeat occasionally on future songs) when she starts naming all the flowers and plants growing in this “ghost town.” It’s imagistic and strange, but alluring.

Or take “The Book Of Right-On”, where she states how she “killed [her] dinner with karate / kick ‘em in the face / taste the body”. It’s a visceral and rare moment of violent imagery, used to bolster… what exactly? The song is willfully obtuse, as she likens herself to a pack animal of some sort and reminds the person she’s singing to that “you know your place.” And what the hell even is “The Book of Right-On”?

I could go on, but I’ll save some of the secrets for you — if, by some chance, they are still secrets. The Milk-Eyed Mender is like a book of adult fairy tales, wilfully intertwining adult woes and concerns with a childlike, misty whimsy and wonder. Newsom’s lyrics convey such oceans of meaning, despite their penchant for nearly buckling under their high-end vocabulary. She would later cool this technique a little, especially on her third and fourth albums, but that still didn’t stop her from later singing words like “Ozymandian” or “etiolated” or “hydrocephalitic” with an infinitely impressive ease.

Beyond her imagery, Newsom displays a keen sense of rhyme and rhythm with her words. Check the internal rhyme, timing, alliteration, and consonance on display in this verse from “The Book of Right-On”:

Do you want to sit at my table?

My fighting fame is fabled

And fortune finds me fit and able

Or what about this mind-boggling verse from “Inflammatory Writ”:

Even mollusks have weddings though solemn and leaden

But you dirge for the dead and take no jam on your bread

Just a supper of salt and a waltz through your empty bed

Or even this spare, natural scene in “Swansea”:

All these ghost towns, wreathed in old loam

(Assateague knee-deep in seafoam)

The mazes of her words lead us down winding corridors, leaving us beside ourselves. It’s easy to miss the intricacies of her writing when the melodies and harp have so much weight, but dig into these songs, and you find a series of little miracles — even down to her grammar and punctuation, as seen in her painstakingly detailed liner notes.

In the grand scheme of Newsom’s discography, The Milk-Eyed Mender might be her ‘worst’, but even saying that makes it sound like it’s bad or not worth listening to or doesn’t measure up to her future records. None of that is true; it is simply that she continued to ascend, refining her skills as a singer, lyricist, musician, and artist. Her stories became more and more complex; her playing got more adventurous; her singing more dynamic and rich. Years have been nothing but kind to Newsom’s work as a musician, and if her debut album feels a little minor in comparison to her later triumphs, so be it.

At the end of the album comes “Clam, Crab, Cockle, Cowrie” (see what I mean about lists?) which has gone on to become another fan favorite. It’s a delicate ballad, plodding along in a sort of slow ambling fashion. Images fly by of bats dissolving, dragons and machines, and (in one image of such breathtaking, ravishing precision) mornings where the sky looks like a road. It’s an enveloping scene.

As we come to the close, Newsom is outstretched atop the water and “waltzing with the open sea.” Before departing, she begs: “Will you just look at me?!” Then, after a series of plaintive, cyclical “oh oh oh”s, the last harp string is plucked, and the album descends into silence. It’s a remarkably fitting end to an album that feels like it is always defying odds. Here is a woman with a unique voice that divided critics and especially listeners; a musical style as steeped in modern folk and indie conventions as classical, world and traditional techniques; and a lyrical game full of 10-point vocabulary words (such as “ululate”, “lateen”, “taciturn” or “poetaster” — Vulture even once published a whole article in tribute to her word choice), allusions, metaphor, and tricky turns of phrase. She wasn’t (and still isn’t) “for everyone” (as loathsome as that phrase can be), but she found her audience due to the sheer magnitude of her talent.

When one considers Joanna Newsom’s place within the freak folk canon, it is somewhat easy to see how she got lumped into that scene — despite how loosely-knit a scene it was. Her general “weirdness” got her in, because that was just a school of indie music that many people got relegated to if they didn’t fit the norm and were on the artsy or psychedelic side. But almost as soon as her name landed alongside her New Weird America brethren, she ascended away from it, into her own echelon, where she more or less remains.

The Milk-Eyed Mender is an impressively auspicious beginning, showing immense promise from a very young age at such an early point in a career. The fact that she has slowed down music production in recent years (in addition to the 20th anniversary of this album, we’re fast-approaching the 15th of her third album Have One On Me and the 10th of her last record Divers both in 2025, and the 20th of her masterpiece of a sophomore album Ys comes in 2026) has made many of us fans longing for more. But even though it’s been almost nine years since her last record (and hopeful signs of a new one are starting to percolate, if the five new songs she debuted at a secret concert last spring are anything to go by) we still have plenty of gifts to pore over and surround hearts with while we wait.

We aren’t eager for more out of greed or out of being tired of the old material; we’re hungry for it because her work is that rich and that fulfilling, and who wouldn’t want to continue to exist in a musical space like hers? Who wouldn’t be intrigued to hear more?

Because that’s the thing: Joanna Newsom doesn’t only create songs — she creates worlds. Twenty years on, the worlds she spun on The Milk-Eyed Mender continue to live on as breathing musical organisms, speckled with endless detail and avenues to wander down. Her musings on life, love, what it means to be a human in this beautiful and terrifying world — they are so rife with feeling and acute observation that one can simply keep spelunking their depths for new beauty. Perhaps that is what struck me in the beginning. Perhaps that is the thing that kept me coming back, despite my initial reservations. Perhaps I started seeing the outlines of those worlds, and desired to mine their innermost caverns for more.

On “This Side of the Blue”, she describes a scene where “we all fall down slack-jawed / To marvel at words”, and says that the only thing we can do “on this side of the blue” is “do what we have to do”. How grateful we should be that Joanna Newsom did, and continues to, do what she has to do. And all we can do is sit back, bear witness, slack-jawed, and marvel.