Here they are: the last great Rockstars of their era. Deerhunter, the colorful unit assembled around shapeshifting maestro Bradford Cox, have managed to be the most lasting and impactful band of a loosely-associated scene that dominated the landscape of American rock music of the millennial age. As this month sees the 15th anniversary of the release of their debut album, it seems only just to take a look at their achievements – so far – release by release.

In slow motion: following the dissolution, dissatisfaction or homogenization of the garage rock-heavy ‘The-Bands’ that spawned around the success of The Strokes’s debut Is This It?, most American music journalists turned towards the promising venture of ‘Blog Acts’ – small bands that had accumulated enough local success to fund EPs or humbly-produced albums. The trend turned out to be a fad that lasted barely one summer, and acts that had been crowned by audiences and critics alike were dismissed just a few months later.

In the meantime, a large number of individual acts that spawned parallel to The Strokes had slowly built complex back-catalogues of sprawling discographies. These bands had clear pop structures at the heart of their material, but combined it with unfiltered bedroom-style DIY production and psychedelic soundscapes, making for occasional detours into noise and ambient. Among them were: Liars, Animal Collective, The Black Lips, Jay Reatard. The fact that these acts, often associates and collaborators, didn’t have an easily identifiable unifying aesthetic is part of why they’ve never been identified under one genre term, even though they often shared line-ups and directly influenced each other.

It was on that fertile soil made up of avant-garde pop, post-punk and psychedelic noise that Deerhunter manifested.

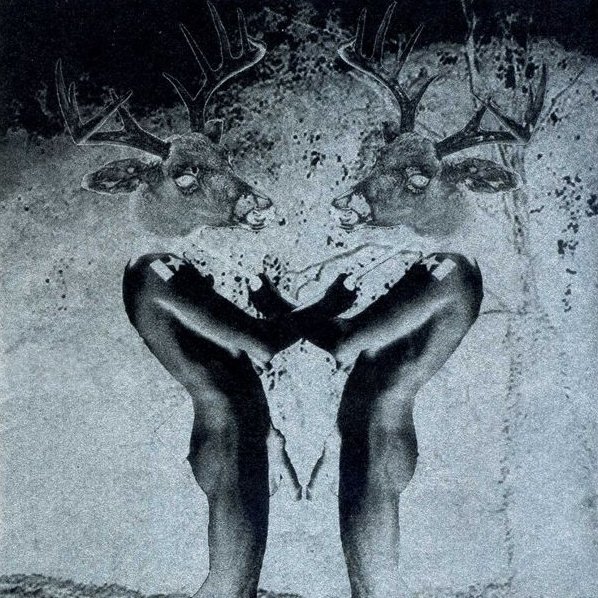

Turn it Up, F***** (2005)

Deerhunter’s harsh, chromatic debut album can be seen as an attempt of ultimate provocation. There’s the title, recycled from a heckler’s sarcastic comment on the band’s live sound. Jared Swiley’s half-erect cock, an outcome of Cox improvising erotica during the photo session, rounding off a mixture of homo-erotic kitsch and American iconography. And finally, the unkempt punk sound that sugarcoats the nine otherwise sparkling dance-punk numbers.

While Cox dismisses the album as a “student film”-like project that documented the band’s limitations moreso than their qualities, it’s rich with the individual aspects that the band would expand upon later on. The talent is evident in the Piper at the Gates of Dawn-like opening to “N. Animals”; “Adorno”’s memorable bass-line; the dueling guitars and adolescent anxiety of “Basement”; and the attempt to merge punk and shoegaze on the album’s lone single “Oceans”. The songs mostly spiral around one key rhythm and climax in harsh noise, making the album feel like the unlikely marriage of Butthole Surfers and Bloc Party. Made up of Cox, drummer Moses Archuleta, bassist Josh Fauver (who stepped in for the band’s deceased original member Justin Bosworth – a recently recuperated heroin addict who broke his neck while skateboarding) and guitarist Colin Mee, the line-up might lacks the touch of future guitarust Lockett Pundt, but still feels valid and lively. Widely underrated, it hasn’t been reissued since its release in 2005 – a crime!

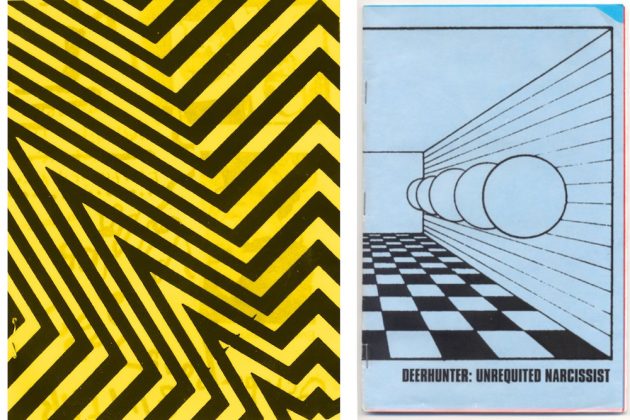

Carve Your Initials Into The Wall Of The Night & Unrequited Narcissist (2005)

These obscure, experimental projects were sold during early touring; CD-Rs with zine-artwork in low numbers. Probably only featuring Cox and Archuleta, both have the feeling of a costume fitting for the sonic structures that would later be explored on Cryptograms.

Carve Your Initials has a slightly more industrial feel to it, probably due to its extended noise orgies and repetitive spoken word-pop, not unlike Ramleh, Flaming Tunes and other British cassette-only releases from the 80s.

Unrequited Narcissist might seem similar at first, but is more interested in nuance. There’s genuine songs here, such as the “He Would Have Laughed”-esque opener “Summer 1991”, tropical percussion on “Spring 1997”, and an odd concept clearly spelled out within the song titles. There’s a hint of the same underwater dance-beats that are found on Slowdive’s 5 EP and shades of Throbbing Gristle, minus the extreme imagery. While maybe not essential, there’s a fragile beauty here fans don’t want to miss out on.

Cryptograms & Fluorescent Grey (2007)

Cryptograms saw a troublesome genesis. A first attempt – recorded by folk musician Samara Lubelski – failed spectacularly. Cox suffered from flu and pneumonia and was battling his disappointment with Deerhunter’s debut. According to him (in comments later redacted) the piano used was out of tune and the 2″ tape machine broke down – horn sections were recorded and in the end inaudible. Cox has described the end product as sounding like “Loveless on mushrooms, […] in not a complimentary way” to Pitchfork, and later used some of it for an experimental online-mixtape.

After ruminating on quitting the band, Cox was comforted by his new friends, the band Liars, who, in their own words, rebuilt his confidence in his abilities. The resulting album was the outcome of three individual sessions in 2005 and 2006, each coming months after the last. The first seven songs were recorded over the coarse of one day, with the ending of “Red Ink” marking the tape spinning off the reel. “White Ink”, “Providence” and “Red Ink” clearly reconnect with Cox’s original approach of creating an ethereal, from his perspective “feminine” record. Meanwhile, “Cryptograms”, “Lake Somerset” and “Octet” feel like a wild mix of psychedelic Krautrock and the sterile post-punk aesthetic of Factory Records (the latter being the result of New York studio Rare Book Room owner Nicholas Vernhes remixing the album after the band wasn’t too satisfied initially).

Resuming recording that winter, Cox once again found himself battling the flu, but managed to record four crystalline pop songs, which were later complimented by the short ambient interlude “Tape Hiss Orchid”. “Spring Hall Convert” and “Hazel St” are more in line with the thoroughly pretty shoegaze of Slowdive than with the influences of the previous session, while “Strange Lights” is a full blown epic of guitar noise, and closing track “Heatherwood” resumes the percussion found on the tour-only releases.

While Cryptograms was in the final mixing stages, the band returned to the studio once more and recorded Fluorescent Grey, an EP which would eventually be assimilated into Cryptograms‘ vinyl release. A continuation of the latter session’s sound, the four tracks are bright, multicolored pop songs, with singalong lyrics and euphoric, noisy climaxes.

But, thematically, they couldn’t have been different: where Cryptograms‘ original material was concerned with adolescent iconography and sexual energy, Fluorescent Grey is existentialist, macabre and less cryptic. The title track weaves the morbid image of dead flesh with sexual awakening, while “Dr. Glass” sees Cox expand on images of the Iraq War, probably taking the name from a minor character in Alan Moore’s Watchmen. Even if “Like New” and “Wash Off”, respectively written about the end of a depressive episode and a hippie selling bad drugs, are a little brighter, Fluorescent Grey bookended Deerhunter’s early, chaotic period.

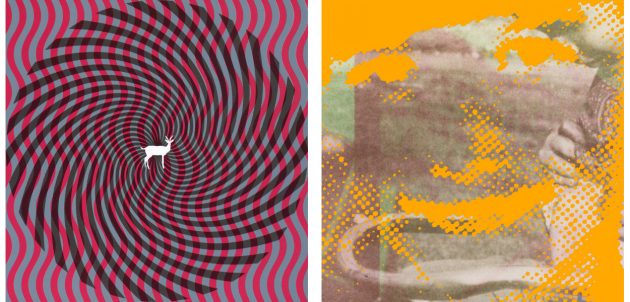

Microcastle & Weird Era Cont. (2008)

Reduced to a four-piece after the drop-out of Mee, Deerhunter rushed back into the studio to record the album that would break them to a larger audience. Microcastle continued their path of the crystalline psychedelia of that started on Fluorescent Grey, but mixes things up significantly.

In “Neither of Us, Uncertainly” and – most prominently – “Agoraphobia”, it includes two tracks composed and sung by Lockett Pundt, with the latter now considered one of the classics of its era. Aiming to remove himself from Cryptograms’ post-punk sound, Cox’s compositions recall American acts of the mid-60s, like The Byrds and Joe Meek. Mostly shedding the feedback-laden sound allowed for more acoustic experimentation, such as on “Microcastle” and “Saved By Old Times” and the record’s centerpiece, a three-song ambient medley.

However, the album’s standout track remains the outstanding “Nothing Ever Happened”, co-written by Cox and Fauver, an unrelenting, insanely memorable mix of Kraut- and punk-rock, which the band expanded during live shows into a 30-minute jam-track, incorporating Patti Smith’s guttural “Horses” repetition into the song’s climactic finale. Fauver is the secret star of Microcastle, as his basslines here are probably the most outstanding of its era, only rivalled by Carlos D.’s early work in Interpol.

Microcastle leaked in mid-summer, months before its release, spoiling Cox’s intention of it being an autumnal experience. A little later, when an over-eager fan realized the link to some DIY-solo tracks that Cox uploaded to the band’s blog led to his personal Mediafire account, a “secret” Deerhunter album was discovered… or stolen, if you want to go with Cox’s more accurate assertion. Intended as a “free surprise” album included with Microcastle, Weird Era Cont. is a loose collection of hypnagogic pop and haunted ambient, a sinister collage that made a turn towards early Velvet Underground and aforementioned Joe Meek’s “I Hear A New World”.

Often ignored due to its – umh – weirdness, the album includes a variety of all-timers, such as the macabre spoken-word piece “Vox Humana”, “Vox Celeste”, and the 10-minute fiery shoegaze reimagining of “Calvary Scars” – a track Cox had refashioned various times on his blog. The uniquely careless attitude of Weird Era Cont. is clear in the art punk of “VHS Dream” and “Operation”, as well as the numerous instrumentals; it’s almost as if we’re witnessing the first attempts at a mixtape of the subjects on the album’s artwork.

Speaking of which, the reliably relentless Cox switched up artwork for the double album various times, confusing some new to the band to this day. By the release of the album, Cox was emotionally exhausted, and had hired guitarist and school friend Whitney Petty (whom Cox described as “cheerleader with an attitude”) to join the band – only for her free spirit to lead her to leaving shortly after.

To his surprise (and probably fuelled by the drama of the past), Microcastle blew up, received widespread praise, and catapulted the band into the limelight, making it the OK Computer of millennial American underground. European concerts in front of 15 people turned into sold out double-bills with The Black Lips and the band was soon picked up by renowned British indie label 4AD who re-released Microcastle/Weird Era Cont. and put them on their roster alongside the likes of The National, Beirut and TV On The Radio.

Rainwater Cassette Exchange (2009)

Fuelled by a new “anything is possible” spirit, the band’s second EP could potentially be their defining statement of the early era. Only five songs long, it perfects the mixture of Cox’s interests in Meek’s tropical rock with Fauver’s New Order basslines, Archuleta’s Kraut rhythms and Pundt’s ethereal guitar style, allowing all four to stand out in their own right. While the climax of the record is probably “Circulation”, with a coda that mixes the duelling guitars of Television with a TV-audio collage, the faux-Caribbean sound of the title track and “Game of Diamonds” and the Strokes-adjacent “Disappearing Ink” and “Famous Last Words” provide a new levity and show the band at their most accessible and harmonious. As the band would soon part ways with longtime producer Vernhes, it would be for the last time in a while Deerhunter sounded happy.

Halcyon Digest (2010)

The new decade started out sinister, as Cox’s close friend Jay Reatard died of a mix of the flu and cocaine intoxication. Music streaming services hit big, forcing labels to rethink strategies of marketing and release. Struck by the impact of Animal Collective’s masterpiece Merriweather Post Pavilion, the band opted for producer Ben H. Allen, whose collaborative approach didn’t sit well with Cox, who saw himself pushed into the (uncomfortable) position of egocentric frontman defending the band’s interests. This resulted in odd moments, such as when Cox tried to kick out Allen for the recording of “Basement Scene” in order to have it be mixed by the 14 year old son of one of the engineers; or when Allen kicked out Cox for the recording of Pundt’s “Desire Lines” (the result, which happens to be Cox’s favorite Deerhunter song, only features his guitar on the first verse).

Surprisingly, this tense atmosphere resulted in what most consider the band’s masterpiece. Cox’s ambition to achieve a unique drum sound as memorable as that on David Bowie’s Low resulted in the hallucinatory opener “Earthquake” and what is probably the band’s most well-known song, the Dennis Cooper-inspired “Helicopter”. Channeling the life story of fictional gay pornstar-cum-junky Dima, the track’s odd mix of dub rhythm and sterile guitars still sounds oddly futuristic and – at times – genuinely frightening, like an unholy marriage of Throbbing Gristle and Pulp. Most of the album resulted from the influences of pre-Beatles pop music, such as Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly, with Cox’s slightly-distorted voice reminiscing on death and social isolation, oftentimes providing a voice of comfort, such as in “Don’t Cry” and “Sailing”. This interest in outsider figures is mirrored in the artwork, which Cox claims came to him when he dropped a book and it opened to display the iconic black and white photo.

The album’s haunted atmosphere is put into sharp focus with its closer, “He Would Have Laughed”. Played by Cox, the icy, Animal Collective-inspired track is titled after a jibe of a Radiohead-forum user that made light of Jay Reatard’s death, shrugging off criticism with “Come on, he would have laughed.” The song casts Reatard as gold digger in the first part, only for the rhythm and ambience to deteriorate into an odd ballad, which has the narrator wonder where his friends went, recounting he once lived on a farm and wondering about the nature of sleeping. Even though Cox plays ignorant on lyrical influences (citing he makes them up on the spot), there’s eerie parallels here to Scott Walker’s “Farmer in the City”, which recounts Pier Paolo Pasolini’s murder. After seven and a half minutes, the track ends abruptly, signifying the sudden death of his friend. A gut punch.

Surprisingly, the first reactions to the album were mixed, with some fans feeling alienated by the odd mixture of futurism, uneasy nostalgia and early 60s rock’n’roll. By the time of writing, it’s widely – and rightfully – considered a standout independent rock album of the last decade.

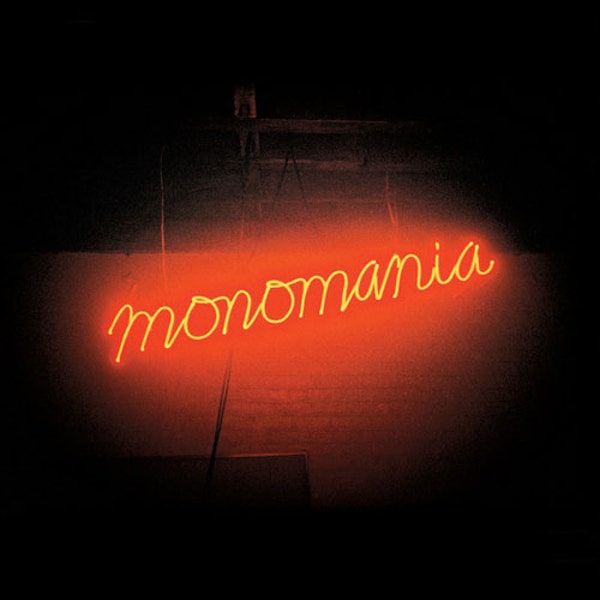

Monomania (2013)

Bradford Cox’s favorite of his records, Monomania was the result of what he later billed as his low point (or as his sister bills it, his “mental hospital record”). Following the death of his friend and Broadcast vocalist Trish Keenan and his cathartic, alcohol-fueled solo-album Parallax, Cox was ready to enter the studio to record an album of “six really long songs and an American flag floating in the background in slow motion” when, all of a sudden, Josh Fauver quit via email and with little to no explanation. When it became clear the bassist couldn’t be swayed back into the band, Deerhunter added Josh McKay (who’s been with them since) on bass, as well as new guitarist Frankie Broyles.

In light of the change-up, the band also decided to abandon their previous concept, leaving us with the song “60 Cycle Hum”, a song played live on the Halcyon Digest tour, as the sole indicator of what could have been. Instead, Cox’s bandmates found interest in a set of dark, depressing tracks he had written following Parallax, dismissingly named by Cox as his “shit era”.

The ensuing sessions resulted in a number of acidic, rough and enticingly weird punk rock songs, brimming with Americana, sex and a sense of anger the group hadn’t showcased since the debut. Most of Monomania’s aesthetic derives itself from Cox’s ongoing fascination with early rock’n’roll, which is quite palpable in “Dream Captain”, “Pensacola”, “Neon Junkyard” and “Nitebike”. But the main inspirations go further back, with Cox naming Hank Williams, Bo Diddley, John Lee Hooker as touchstones. This shift to blues and country aligned itself with Cox now full-on dismissal of indie rock culture, indulging in a full-on dismantling of his public figure in a number of quite baffling interviews and a now legendary appearance on Jimmy Fallon, where a bronchitis-suffering, Ramones-esque version of Cox spat blood and shuffled through empty studio corridors while his bandmates turned the title track into a chugging guitar maelstrom. To most, it’s that performance which classified “Monomania” as the big standout of the album, with Cox repeating the title ad nauseum as guitar feedback and the sound of a roaring motorbike engine deafen the listener.

But songs like Pundt’s “The Missing” and Cox’s eerie, delirious rumination of his brother’s passing in “T.H.M.” are some of the band’s best material. It’s funny that the record, hyped up in advance of its release by Black Lips’ Cole Alexander as one of the defining punk albums of its era, was dismissed as “respectable disappointment” upon release, as it’s one of the most unique and uncanny rock albums of the new century. With each additional listen, it reveals itself as an oddly magnetic opal of majestic neon colors buried in stark black marble.

Fading Frontier (2015)

For the first time in a while, Deerhunter seemed stable. Cox had settled into his house and adopted a dog, Faulkner. Pundt had become a father and Archuleta got married. Like many guitarists, Broyles left following an extended tour, but according to all reports, the band finally had reached a healthy balance. But – as so often in Deerhunterverse – misfortune struck the band suddenly in December 2014, when Cox, walking Faulkner, was hit by a car. The injuries were grave, and when Cox finally emerged from hospital, he was overcome by debilitating depression. Now on anti-depressants, Cox became a recluse and saw his medication cancel out the manic, libidinal energy he used to fuel Monomania and the previous work.

The longing for safety and harmony Cox described in interviews of the time is instrumental to the resulting aesthetic. Tonally inspired by the sophisticated 80s pop of INXS and Tears for Fears, the pastoral Fading Frontier is probably the closest the band will ever come to a genuine pop album. The introspective and often fairly transparent lyrics remove the morbid yearning of the band’s previous albums and allow, for the first time, a sense of clear comfort to take a hold.

This is most obvious in “Breaker”, where Cox resumes “I’m alive / and that’s something,” while Pundt takes over vocal duty during the chorus, as well as taking the lead on the calmingly reassuring “Take Care”. That of course doesn’t mean that Cox’s gleeful ambivalence and existential anxiety isn’t heard seeping through the cracks: “Duplex Planet” is a melancholic rumination on ageing and dementia (a theme that seems to reoccur in Cox’s lyricst), “Snakeskin” feels like an uncanny little sister to “Sympathy for the Devil”, and the odd ambient-ish track “Leather and Wood” disrupts the pacing and leaves the listener with a strange unease.

Like its predecessor, Fading Frontier initially divided the band’s audience. While some felt it was too bright and sober in comparison to Deerhunter’s previous work, it also aligned itself perfectly with the atmosphere of late Obama-era bliss and spawned what was probably their best live shows, including regular 30-minute improvisational renditions of “Nothing Ever Happened”. In a way, and out of the ashes of a near-death experience, Deerhunter seemed to have finally found their happy end.

Double Dream of Spring (2018)

After an extended break and odd ruminations of a line-up change, Deerhunter were back on tour and immediately announced a new cassette-only album. Titled after a de Chirico painting, Double Dream of Spring feels just like that: an obscure, experimental Deerhunter album you’d encounter in a dream. It reconnects with the aesthetics of their early CD-R releases, but abandons the noisy industrial leanings in favor of horns and keys. Many of the instrumental tracks seem to be built around gentle loops, which hint at Krautrock influences, while others such as “Serenity 1919 (Ives)” revisit the eerie balladry of “Dr. Glass”.

Double Dream of Spring has become a much sought-after rarity, especially as any copy uploaded to the internet continues to be scrubbed away within hours of a drop. It exists in a strange spot, somewhere between insight into artistic development and loose jam session. It’s fleeting and fragile and would likely collapse under widespread critical gazing. As it is, it’s a nice, brief glimpse of something delicate and personal.

Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? & “Timebends” (2019)

Officially adding keyboarder Javier Morales to the line-up, the band was back to a five piece – the previously teased line-up changes had not materialized beyond the rumor stage. Following the release of cryptic typographic online art and extensive recording sessions led by Cate Le Bon, the band embarked on a sprawling pre-release tour, that came to a brief disruption when word arrived that former bassist Josh Fauver had died. Later on, Cox would reveal the two had finally reconnected and had been very close prior to his sudden death, so it’s eerie how one of the lasting themes on Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? is sudden death. And it wouldn’t be the only prophetic parallel here; since its release, Cox’s self-administered title of “prophet for the end times” seems to have proven true.

There’s an ongoing apocalyptic theme to be found on Disappeared? that ties directly back to Fluorescent Grey. “No One’s Sleeping” was written in the wake of the murder of UK politician Jo Cox, but now recalls the daily imagery of American protests. “Element” is about climate change, but its anxious dissonance might as well have described the Covid-19 quarantine, reflections of which can also be heard in “Death in Midsummer” and “Futurism”. And then there’s “What Happens to People?”, which revisits the themes of “Duplex Planet” and could be as much about a passing relative as it seems to address the departed Fauver.

Under Le Bon’s watch, tracks like “Greenpoint Gothic”, “Tarnung” and “Détournement” are sonically reminiscent of David Bowie’s Berlin trilogy – probably what Cox meant when he characterized the overall aesthetic of the project as “brutalist”. Indeed, with its weird mixture of plucked strings, icy synths, Marimbas and eerie vocoder experiments, the record is the closest Deerhunter have come to fashion something that resembles Bowie’s Low. It’s their most underrated work, as it’s the most nuanced, suggestive and multi-layered they’ve ever been.

On their post-release tour, the band added a violinist, which expands the songs into rich psychedelic tapestries, somewhere between Television and The Velvet Underground. They expanded this sound on the essential post-album track “Timebends”. Clocking in at over 12 minutes, the song is an almost lurid post-script, filled with Robert Fripp-styled guitars, tonal shifts and poetic imagery, that feels both like the closing of one chapter and the first rays of a new dawn – only time will tell whether it’s a true indicator of what’s to come from the continually evolving act.