The Flaming Lips – The Terror

[Warner/Bella Union; 2013]

Because of their exuberant, technicolor stage get-up, it’s easy to dismiss Oklahoma City’s The Flaming Lips as a bunch of naive, slightly out-of-touch dreamers. Even if that is – to some extent – true, examining some of the band’s most cogent lyrics, you can’t help but wonder whether that unabating optimism isn’t anchored by something, well, darker.

If the band’s most famous lyric (“Everyone you know someday will die”, from “Do You Realize???”) isn’t a hint of Wayne Coyne’s sporadic meanderings into more fatalist, death-obsessed prose, get a load of “All We Have Is Now”, a tale of a man warning his past self his relationship is doomed to fail. I mean, come on… that’s dark as fuck.

In 2013, any sort of doubt of The Flaming Lips’ darker side was cast aside when they released The Terror. With its opaque, eerie Suicide-indebted sonics, the band truly doubled down on more downcast, cobwebbed emotional strains. It’s like the band deliberately pulled down that Wizard Of Oz smoke-and-mirrors facade and showed the existential despair underneath that compelled them to maybe gloriously overcompensate with all these festive shenanigans.

The Terror truly is an underestimated masterpiece, because even the most die-hard Flaming Lips zealots couldn’t have seen it coming from a mile away. From the corrosive industrial pounce of “Look… The Sun Is Rising”, the ethereal, radioactive haze of “Butterfly, How Long It Takes To Die”, and the festering, throbbing, Steven Drozd-sung “Turning Violent”. The Terror is unapologetic and forthcoming about its sheer dread. Which somehow makes it even more disturbing than records by bands who court the worst of human traits by default. – Jasper Willems

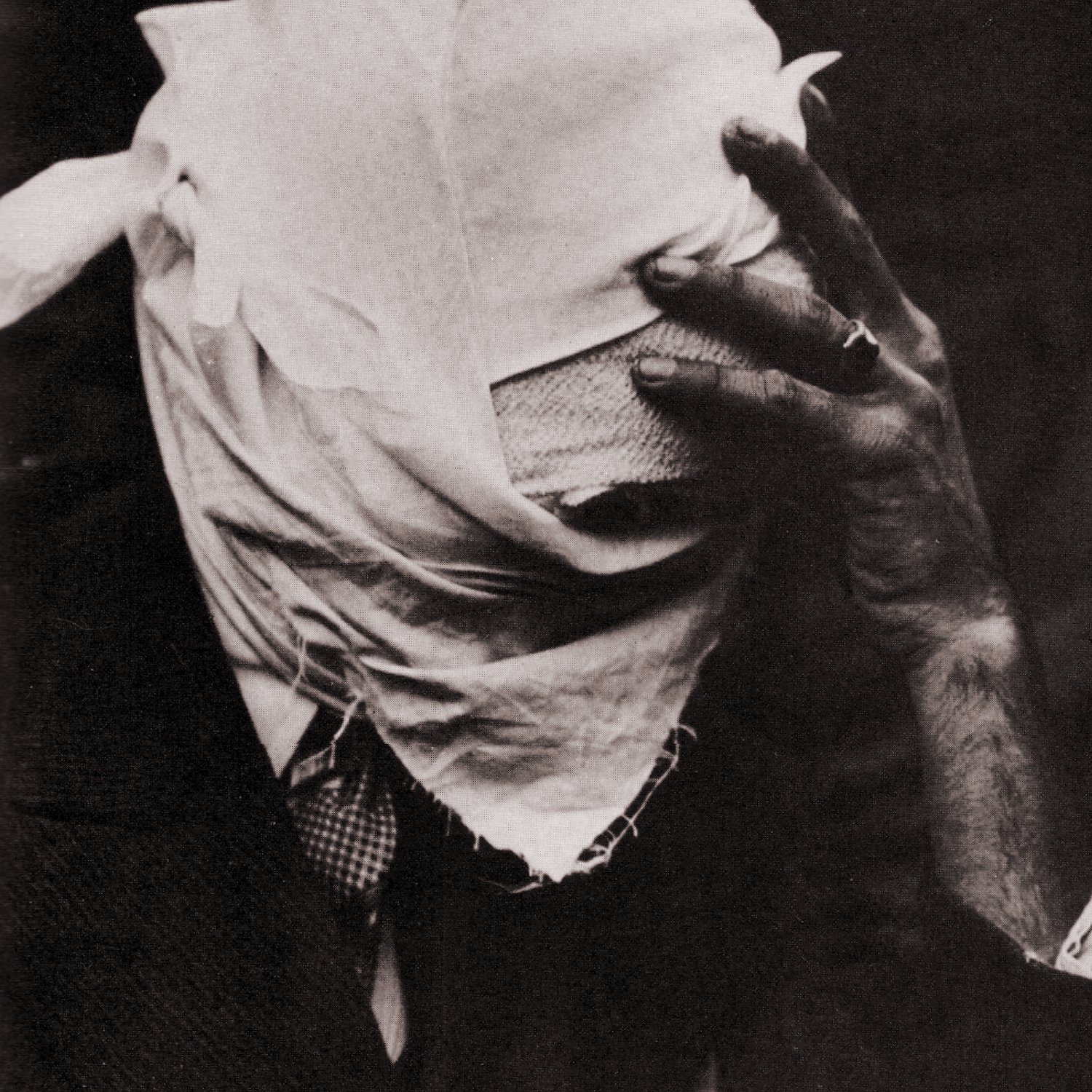

Giles Corey – Giles Corey

[Enemies List Home Recordings; 2011]

Where to start with an album like Giles Corey? Dan Barrett’s first solo album captures a man reckoning with suicidal thoughts in what feels like real time, amidst clattering percussion, guitar notes that ring out into infinity, and endlessly reverberating rooms. His hopelessly dark, devastating depression has him wrestling with the question he puts to himself at the start of the album’s accompanying book: “If I did not wish to be alive, did I wish to be dead?”

There’s a lot to be said about (and terrified of) by the song’s opening track “The Haunting Presence” where we hear Barrett unravel, his lyrics screamed into cacophonous harmonies until we eventually hear him hammer at his piano while weeping. But his crushing despair is equally on show on the doom-folk jangle of “Grave Filled With Books”, the hushed and distant hum of “I’m Going To Do It”, or the trickling acoustic notes of “Nobody’s Ever Going To Want Me”. No track here doesn’t have something that makes the hairs on the back your neck stand up, be it a rush of emotional noise, a distant EVP sample hiding in the corner of the mix, or a frank and tragic lyric (“I’m going to kill my self / so there won’t be nothing left”).

Perhaps it’s a personal connection from having been on the edge like Barrett has, but the rawness of the music on Giles Corey feels impossible not to be enveloped and troubled by in equal measure. Perhaps the mythos surrounding it (do your best to find Robert Voor) distract from the emotional plea at the centre of it all, but if anything, it speaks to the state of a man forming a new reality to escape his own. Wrap yourself up in stories of ancestral witches, ghostly presences, the spectre of death, and a Voor’s Head Device; you’re not likely to find something as unsettlingly bleak and human as Giles Corey. – Ray Finlayson

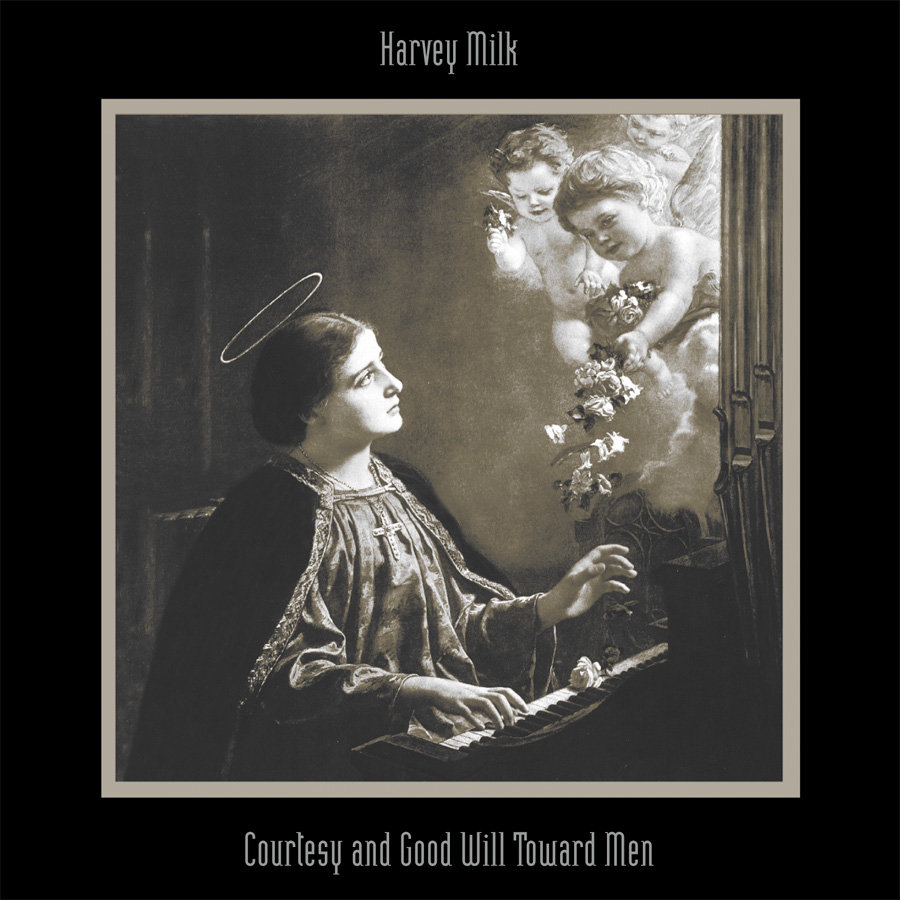

Harvey Milk – Courtesy and Good Will Toward Men

[Reproductive; 1996]

There’s not a whole lot of behind-the-scenes information available about Courtesy and Good Will Toward Men, but back-to-back song titles “My Broken Heart Will Never Mend” and “I Feel Miserable” suggest that Harvey Milk were going through it, and the listening experience brings you right into the depths with them. Appropriate for a sludge band, Courtesy is so viscous, hearing it can feel like drowning on dry land. It takes a certain state of mind to create a guitar tone that despondent.

It’s such a heavy experience, that the only time that feels appropriate for listening to it are when those song titles are your running thoughts and you, in a cruel irony, can’t even summon the motivation to put on an album that puts your anguish into auditory form. Guiding you through the darkness is vocalist Creston Spiers, whose tortured bellow could send Tom Waits scrambling up a tree for refuge. Oftentimes crushing, but at others, tranquil, and with a Leonard Cohen cover to boot, Courtesy and Good Will Toward Men offers you its hand, only to pull you further down. – Brody Kenny

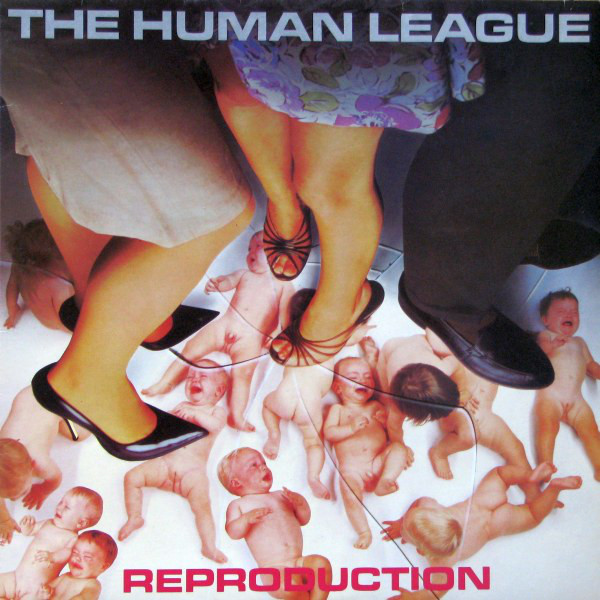

The Human League – Reproduction

[Virgin; 1979]

Punk didn’t die – it transformed. On one side were those who followed their American inspirations to fully indulge in rock’n’roll glory and, well power pop. Then there were those wading through the depths of foreign cultures and marginalized atonal genres to craft complex post-punk sounds. But parallel to that, a new generation of musicians realized that the punk ethos demanded to abandon traditional instruments altogether. Informed by The Normal’s single “Warm Leatherette” and fronted by a hospital porter and non-musician known for his sharp style, The Human League picked up a bunch of synthesizers and generated icy structures that interpreted J.G. Ballard and Kraftwerk as cyberpunk epics. By 1978, David Bowie declared them the future of pop music. The first of their kind, the quartet crafted a vaudevillian album that married pop melodies with toxic nihilism and sounded more like it originated on Giedi Prime. Their sound was so grim that when Virgin records signed them, they demanded the band take up real instruments and deliver hit music – needless to say, that didn’t go well, and the band was allowed to fashion debut album Reproduction according to their tastes.

Listening to the album 40 years later, Reproduction’s dystopian machine world remains barren and impossible to resolve. “Circus of Death” uses a sample from a radio program, a circus melody, spoken word and obscure dance macabre imagery – the track was accompanied by a lengthy explanation as to its intention and meaning, which reads like a knowing, bitter wink to inquisitive journalists. “Blind Youth” and “Zero as a Limit” directly reference Ballard’s books High Rise (“We’ve had it easy, we should be glad / High-rise living’s not so bad / Dehumanisation / Is such a big word / It’s been around since Richard The Third”) and Crash. By poking fun at former punks turning into high rise dwellers and opening up to the eroticism of crashing cars, Human League dispatched the idea of punk as a story of failure. Yet there is a timeless universality to its essence: Reproduction connects the unemployment crisis and rubbish-laden streets of then-current Britain to the spiritual degradation that comes with middle age and urban malaise. It would go on to inspire projects like Depeche Mode and Fad Gadget and remains the darkest synthpop album ever made. – John Wohlmacher

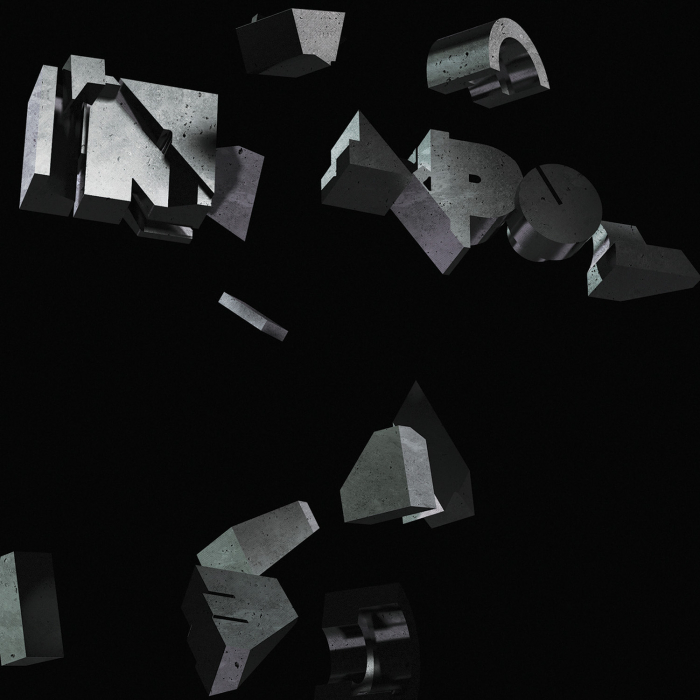

Interpol – Interpol

[Matador; 2010]

The most polarising album of Interpol’s entire career, it may be a musical faux pas to say Interpol is the band’s darkest work. In fact, one could argue that trying to find Interpol’s darkest album is essentially like arguing over different shades of black. However, there is a wholly different vibe on this – to be frank – massively underrated project that still stands out amongst their discography. Being the last release involving bass player Carlos Dengler, lead singer Paul Banks’ lyrics seemed more transparent and more overt in their misery – but still not completely lacking opaqueness.

While it seems that fans warmed up to this release in later years, Interpol still deserves a revisit from those who dismissed it. Starting off with rather conventional Interpol tracks, the album slowly and seamlessly descends into absolute pitch darkness by its conclusion. A sad and sometimes visceral portrayal of someone reeling and unravelling from a definitive heartbreak, this is truly some of the band’s most striking and emotionally depleting work.

While Interpol continues their post-punk sound, the guitar work feels desolate and sinister, almost ambient in its purpose. Exploring the pain that arises from yearning for someone’s love, heartbreak and the accompanying dark mindset that comes from being entrenched in realising you’ve lost a relationship forever, this is truly one of the band’s very personal works. The biggest stroke of genius on Interpol are the album’s interconnected final three tracks “Try It On”, “All Of The Ways” and “The Undoing”. The first instalment shocks by starting with a piano riff that becomes the building block for which this narrative of romantic grief and painful acceptance begins (“Please explore my love’s endurance / And stay, stay / Please enjoy my love’s exhortations / No way, no fucking way, no.”) “All of the Ways” is an uneasy listen that explores someone ominously ruminating on an ex who has found a new relationship; the verses are essentially a series of questions directed at this new lover that feel underlined in red including the alarming “Does he know that I wait for all time?” The most frightening aspect is the chorus in which Banks’ sings “All of the ways you will make it up / Make it up for me” as if patiently awaiting for the ex to come crawling back. But the album’s finale “The Undoing” is an epic and dismal masterpiece – and perhaps one of the most cinematic tracks the band has ever made – which evokes the feeling of being irreparably shattered at realising a love is lost forever; “I was chased, thrilled and altered / Chasing my damage,” admits Banks. It seems he is in a purgatorial mindset where he repeats the same phrase “I would wait / Please, please the place we’re in now.” It is a breath-taking and destroying conclusion to this album that feels like a dagger to the heart – and pushing it in even deeper. – JT Early

King Woman – Created In The Image of Suffering

[Relapse; 2017]

On Created in the Image of Suffering, King Woman’s 2017 debut, Kristina Esfandiari’s evocative lamentations are accompanied by hypnotic sonic mixes, the album plunging a listener into narcotized despondence. On “Deny”, Esfandiari sings: “Jesus … I’m lacking the spirit / I’m losing the heart.” Her voice unfolds above distorted guitars and militaristic drums: weary but compelling, chthonic but lucid, scornful but fragile. In at least two places on this track, she hints at a scream, muting it prior to catharsis.

“Father do you forgive the one who beats his son?” Esfandiari moans on “Shame”, presenting an alternate version of the Jesus-and-God crucifixion script and questioning “the Father’s” right to self-absolve, given the enormity of his betrayal. She then proclaims: “Don’t hide the shame that’s in your eyes,” subverting the biblical portrayal of Adam and Eve. In Esfandiari’s version, it’s God who basks in shame rather than wayward humans or her persona, who represents a contemporized and mutinous Eve.

On “Hierophant”, wiry guitars wrap around Esfandiari’s voice as she sings, “I’ve gotta be your lover,” sexualizing the relationship between human and God, a Blakean delineation that recasts the Christian deity as both tempter and abuser. The album concludes with the epic “Hem,” stentorian guitars and staccato drums framing Esfandiari’s voice as she pleads, “Won’t you help me out?” The track unfolds toward a cacophonous conclusion, the final minute of the piece and album featuring what sounds like a melodic psalm, the coda to a disturbing journey through consternation, despair, and heretical inquiry. – John Amen

Kino – Чёрный Альбом

[1990; Metadigital]

Кино (Kino) are a Russian rock band, often classified as post-punk or new wave. They have a cult following in Russia and in countries of the former USSR and generally considered to be the best Russian rock band to ever have existed. The frontman and main songwriter, Viktor Tsoy, went through two distinct periods in his artistry: first, was an acoustic bard-inspired folk music with melancholic lyrics, in the last his lyrics turned into almost epic poems with intensely dark themes and the music of the band switched to a more post-punk almost dark wave sound influenced by such albums as The Cure’s Faith and Joy Division’s Closer. Чёрный Альбом is their last album, released posthumously in 1990 following Tsoy’s death in a car crash. It is absolutely entrenched in darkness and at times feels like the songwriter had a premonition of his imminent passing.

Lyrically, the overarching theme is departure. In his heroic and epic poems of previous releases, that theme was also present, but was not prevalent. Elsewhere on Чёрный Альбом are themes of fate of mankind, and anxiety about what tomorrow will bring, all of which are expressed both directly and quite ambiguously.

This album is always viewed from the standpoint of Tsoy’s untimely death, which brings a very mystical mood of the unknown. The last track is only 30 seconds long as it’s a demo that the band did not have the time to complete, and it’s additionally heartbreaking because anyone who has heard Tsoy’s early works will feel like it’s a flashback to those days. Along with this album I’d like to suggest anyone interested to watch the film Leto, which is by Kirill Serebrennikov and is a fictional biopic about Tsoy’s early days and Kino rising to become the most important band of their time. – Aleks Smirnov

Kreng – L’Autopsie Phénoménale de Dieu

[Miasmah; 2009]

The debut album from Belgian artist Pepijn Caudron (aka Kreng) showcases what he does best: theatrical sinisterness, L’Autopsie Phénoménale de Dieu is a haunting 55 minute journey, full of pregnant, haunting silences, whispered voices, and scattered instrumentation. It’s like tentatively exploring all the rooms in a haunted house: you never know quite what is lurking behind each door, and even though there isn’t anything that counts as a jump scare to be found, the menacing feeling is very real. Caudron is something of a master weaver here, stringing together a plethora of samples, field recordings, and found sounds with additional instruments. Even when he has just a brushed snare playing, or a long, screeching violin note, the tension is hung high in the air, a real sense of dread furtively hiding.

L’Autopsie is disturbingly inviting though, practically beckoning you with an extended, skeletal finger. It almost feels like Caudron’s instrumentation is a red herring: a classical piano piece, or a smattering of light free jazz may seem innocuous enough at first glance, but it’s never just as it seems. You might hear Chopin’s sombre “Prelude No. 20 in C minor” on “Meisje In Auto” for instance, but that its enveloped by the sound of a young woman sobbing makes it both deeply melancholic and immensely disturbing. Caudron thrives in these kinds of moments, inking his surroundings with haunting noises. “Transmutation Device” sounds like a piano playing itself from within, complete with unidentifiable scurrying of some sort, while it’s hard to determine if the panting voice on “In De Berm – Part 3” is that of pain or that of pleasure. An operatic soprano repeatedly cuts through the noises across the album, while percussion clatters and jumbles over pressing orchestral drones. Like the Erik Skodvin-made artwork, the album feels like a glimpse of something caught in the air through a shaft of light: menacing, mocking, and somehow knowingly evil. – Ray Finlayson

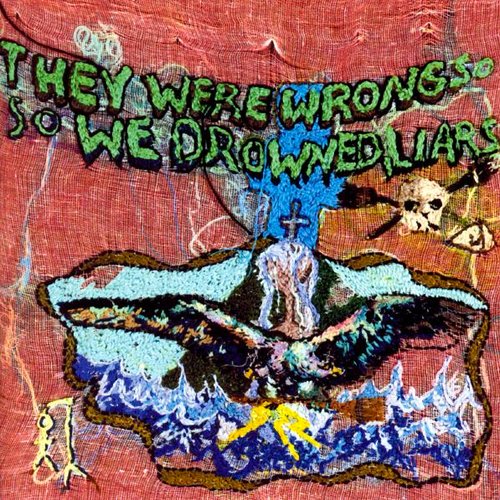

Liars – They Were Wrong, So We Drowned

[Mute; 2004]

If you were to pick up a physical copy of They Were Wrong, So We Drowned, you’d already know it was a dark album. From the manically scrawled cover art, to the track titles like “We Fenced Other Gardens With The Bones Of Our Own” and “They Don’t Want Your Corn – They Want Your Kids”, not to mention the album’s title itself, you might start to feel a tingle move up your arms, as if you’re holding some collection of DVRK MAGIKS whose malevolent power is seeping into your body.

Liars recorded the album deep in a New Jersey forest and took inspiration from witchcraft. Even if you didn’t know these facts ahead of time, you’d get some sense of it in listening to the ritualistic songs within. Despite the relatively lo-fi recording, it’s possible to envision the band in some dingy studio, in a circle, playing as if summoning beasts from beyond. The music is imposing; rhythmically driven, with unrepentant beats and bass adding a physicality to the hypnotic mantras they sing in off-key unison. Synthesizer tones whizz and curdle around in the atmosphere, like conjured spirits appearing and flying off into the dark night to terrorise.

There’s little to comfort here. Even the playfully titled tracks like “There’s Always Room on the Broom” and “If You’re A Wizard Then Why Do You Wear Glasses?” are full of hair-raising tension and demonic harmonising. But therein is the brilliance of They Were Wrong, So We Drowned, it’s meant to scare you – but simultaneously it fascinates you. You can’t help but be drawn closer to Liars’ circle of spells, and soon you’ll be another member of their dancing and chanting coven. – Rob Hakimian

Low – Double Negative

[Sub Pop; 2018]

The first thing you hear on Low’s 12th album Double Negative is wincing static of disillusionment. The slowcore legends have never been known for their sunny vibes – though their music certainly isn’t without it – it’s here within the walls of static that the band captured the bleakness of our world in 2018. Stuck between one bad choice and another, Double Negative does little to ease that pain, and instead it walks us all off into a noisy abyss by way of the solemn tenderness of Mimi Parker on “Fly”. Here, Parker relents the unfortunate gravity of the situation, “You’re telling me just one more / I keep it like it’s torture / Keep my body like a soldier / You gotta tell me when it’s over.”

Then there’s the oblique “Tempest” that slides us closer to this oblivion, or the dusky clouds that descend upon us in “Rome (Always In the Dark)” where Alan Sparhawk likens the toppling of the great empire to the current state of affairs – all the while vaguely illustrating just how fucked we are “Who can make a panic / At the end of the night / Warmness that happens / Then they tear you up.” On the one hand Double Negative is a spiritual successor to their almost-as-bleak 2007 underrated masterpiece Drums & Guns. On the other, it shares much in common with another classic noted for its separatist nature – Loveless.

If there’s a moment to sum up the album, it’s the closer “Disarray”, which finds the band taking full advantage of producer/engineer BJ Burton’s talents. Striking a healthy balance between the cold and Godless world he helped create in Bon Iver’s 22, A Million, and Parker’s angelic disposition of hope, Low brough one of their greatest albums full circle and cast us out into oblivion – which is where we stayed for what seemed like an eternity. – Tim Sentz

Manchester Orchestra – A Black Mile to the Surface

[Loma Vista; 2017]

A massive innovation for Manchester Orchestra, A Black Mile to the Surface is a high-concept, cinematic opus that leaves a hollow feeling in its wake. Lead singer Andy Hull weaves a bleak and complex narrative surrounding a mining town in South Dakota and a fictional man who takes a psychological turn for the worse after a horrible childhood. However, what adds an unorthodox personal layer is how lead singer Andy Hull interweaves lyrical themes of his anxieties over his impending fatherhood at the time.

Tracks like “The Moth” are intense and enraged as if surveying your town burning in an inferno from the top of a cliff – and when the post-chorus is an anguished scream it invokes even more vivid emotion. While “Lead, SD” feels as if you’re inside a factory that creates pneumatic machinery and also intersects the fictional narrative with his own doubts with being a parent (“Is this temporary?/I just heard I’m gonna be a dad/South Dakota every winter someone loses it”) – delivered very quickly as if it’s something he has to blurt out before he convinces himself otherwise. While the album’s two central and tragic songs are “The Alien” and “The Grocery” where the fictional protagonist goes from an unhappy childhood to an unhappy fate in adulthood. The former is a soft and melancholic rumination on the effects of being raised in an unhappy home. As Andy sings about medicated fathers and severing ties with higher powers (“Made a pact with you and God / If you don’t move I swear to you I’m gonna make you”), you can’t help but feel sympathetic. It provides a foundation for the following track’s tragedy in which our protagonist goes to a grocery store with a gun, commits murder and attempts suicide. It’s a brutally miserable pair of tracks (“So you load up your pistol and you press it to your lips / And you squeeze on the trigger / All it does is clicks”) that are beautiful and affecting.

A vivid, lyrically-rich exploration on the sad fate of someone affected by a cruel world and Andy’s navigation of parental anxieties, A Black Mile to the Surface is simultaneously bleak and beautiful. The imagery in the album title alone seems to summarise the central question: can we make the effort to ascend out of our darkness or remain down below where the light is just a barely discerned pinprick? – JT Early

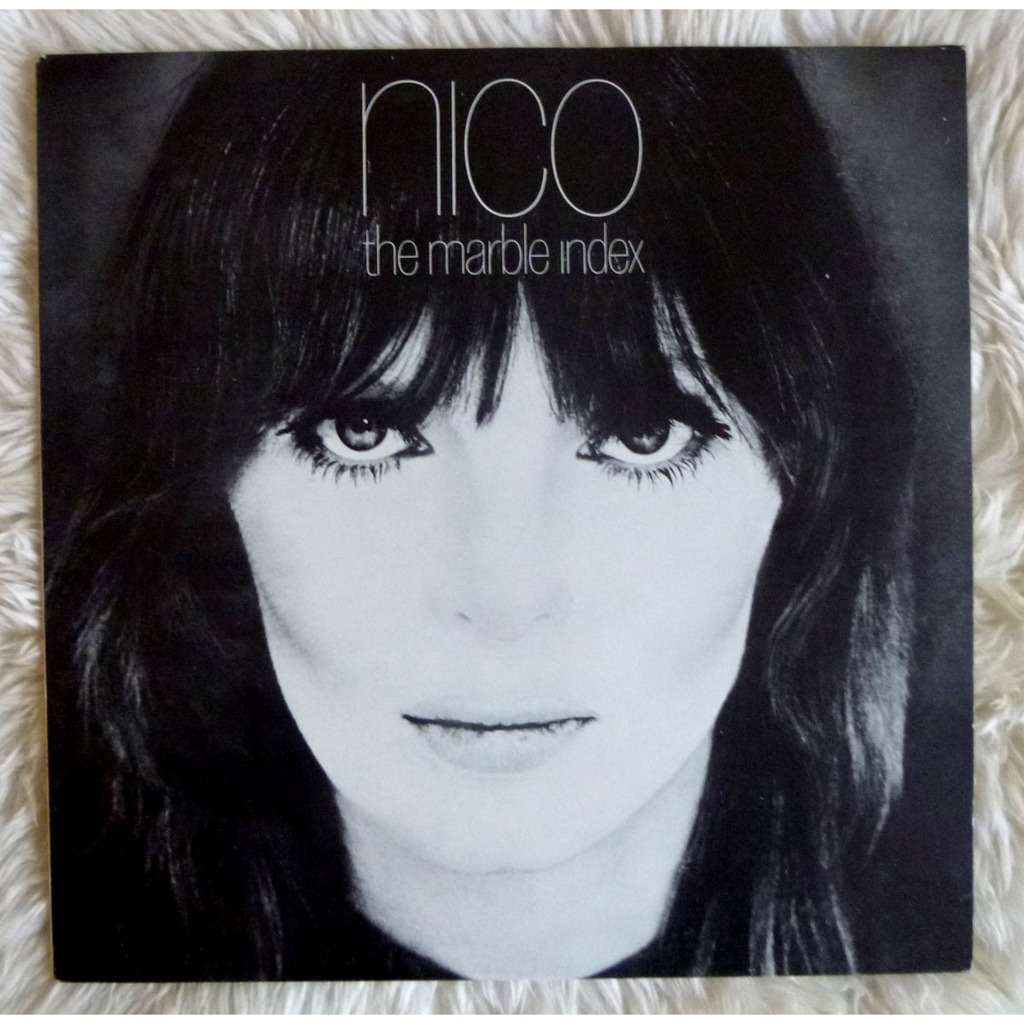

Nico – The Marble Index

[Elektra; 1968]

The previous year’s Chelsea Girl had situated Nico as a chanteuse of melancholy autumnal ballads; there is real beauty in a lot of that material but, crucially, the songs weren’t hers. Inspired to try her hand at writing her own songs, Nico chose the creaking, wheezing sound of the harmonium pump organ to build the foundations for her icily bleak, funereal songs, sung in a stentorian vibrato-rich voice.

She revealed herself to be a composer of depth and originality, and there is a real dark beauty to her melodies – the stark neo-classicism of “No One Is There” aches with sorrow and despair (“he is calling and throwing his arms up in the air / and no one is there”), the truly frightening “Facing the Wind” is a clattering maze of confusion amid thunderous piano, while the spectral “Evening of Light”, with its relentless John Cale arrangement that reaches an Rosemary’s Baby-style apex with screeching violas, is one of the creepiest, most haunting songs in Nico’s catalogue. (Look out for the proto-Wicker Man promo clip featuring a painted Iggy Pop.)

And what about “Ari’s Song”, the bleakest lullaby of all? “Sail away, sail away my little boy…” sings Nico over a breathless harmonium and piercing Bosun’s pipe. Dark and beautiful, The Marble Index is a masterpiece of icy beauty. – Matthew Barton

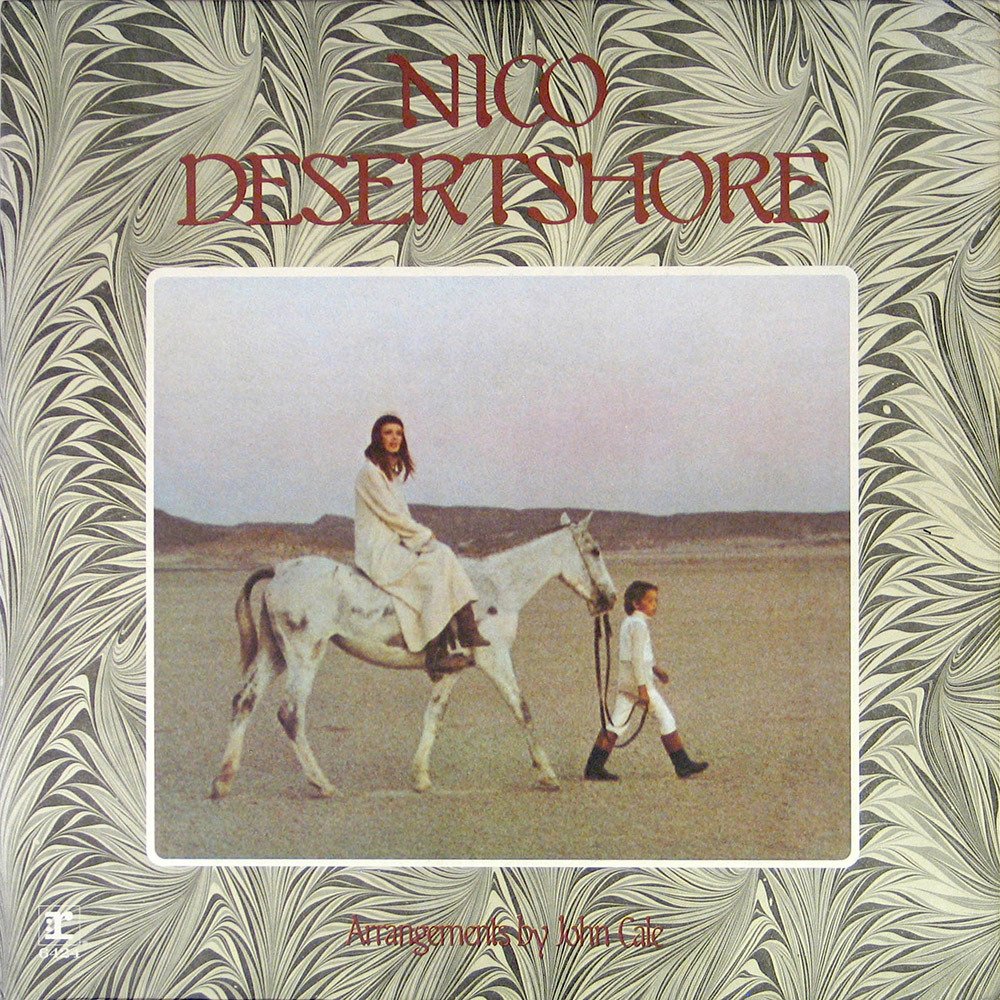

Nico – Desertshore

[Reprise; 1970]

The second album of a supposed trilogy (The Marble Index precedes it and The End… follows), Desertshore was released in late 1970 at a turning point in Nico‘s career, when her solo material was finally achieving cult status and a relationship with French filmmaker Philippe Garrel further encouraged a connection to the avant-garde—and heroin.

Inspired by (and conceived in parallel with) Garrel’s poetic film essay La Cicatrice Intérieure, Desertshore marked Nico’s return to Europe and solidified her status as a transversal artist. Featured in both the film and the album is a 7-year old Ari Boulogne, Nico’s son with Alain Delon. The actor never having acknowledged paternity, Ari’s childhood was split between following his mom around in her several artistic endeavours (he also appears in Warhol’s 1966 film Chelsea Girls) and a semi-idyllic country life in the Paris suburbs with Delon’s mother, who always considered him her grandson. Ari’s bohemian, tumultuous upbringing is reflected on his angelic voice hauntingly singing “Le Petit Chevalier”, a track that often feels like a symbolic representation of Desertshore‘s entire tone, navigating through a fascinating yet dense fog that seems to instantly paralyse everything it touches like a centuries-old malediction.

Although it’s The Marble Index that is usually seen as Nico’s definite chef d’oeuvre, Desertshore‘s evocative landscapes are somewhat easier to visualise (probably due to it having been originally envisioned as a soundtrack), throwing us into the abyss from the first note of “Janitor of Lunacy” (composed as a tribute to Brian Jones, deceased the previous year) until “All That Is My Own”‘s very end. Yet the funniest thing about Desertshore is that the album isn’t even half an hour long; but the trademark heaviness of Nico’s harmonium and overall hypnotic plunge into the deepest pits of existential desolation always make it sound like we’ve been abandoned in despairing wilderness for an eternity. – Ana Leorne

Portishead – Third

[Island/Mercury; 2008]

While Portishead never possessed a reputation for being uplifting, one could always take refuge in the slick grooves of their trip-hop productions. Yet their long-awaited album Third moved on from their established sound into something equal parts fascinating, harrowing and chilling. Here, instead of sadly bopping to their dismal dance, Portishead confront an asphyxiating and relentless darkness that for the band, proves their experimental tendencies were sharper than ever – dangerously so.

Across 11 tracks, the band weave a world out of garrote wires that explore abject loneliness, falling out with faith, loss, self-hatred and the inability to maintain oneself. These lyrical themes are delivered by Beth Gibbons whose voice is even more tremulous and despairing than it had been on Dummy or Portishead. From opening track “Silence”, which feels like the score to a particularly sinister Western film it is clear that the band expanded their scope to explore different kinds of dread. Perhaps it’s the creeping shuffle of “Hunter” which feels like someone is approaching you while dragging a corpse from a sack, or maybe the ominous “The Rip” – a beautiful, guitar-driven piece of melancholia where Beth asks “Will I follow?” as regards the “dark underneath.” Some songs such as “Machine Gun” are just blatantly frightening – a combination of eerie synths and a startling beat that invokes the feeling of bullets ripping through an abyss of ice-cold water. The finale track “Threads” is the jagged pinnacle of this masterpiece, with ominous, sluggish guitar that transitions into a jarring clash of violent drumming. As Beth’s screams of “damned one” fade out, it is replaced by an apocalyptic synth-klaxon noise that repeats and raises the hair on the arms. Somehow, the album manages to end like we’ve reached the entrance into an even darker underworld.

Third may not have been the exact follow-up to their previous two albums that fans wanted, but you can’t deny that this project makes a searing impact. It is a fully realised portrait of the horror of being isolated with your thoughts while the world continues on unyielding. – JT Early

Listen along with our Darkest Albums Spotify playlist