With 2010’s High Violet, The National reached a crescendo, striking a balance between panoramic rock and elegant sound-art. Assisted lyrically by co-writer Carin Besser, singer Matt Berninger perfected his persona: a confluence of various stock characters, the narcissist, self-loather, romantic, slouch, and prickly poet. The sequence showed the band employing a sublime array of sonics, Aaron and Bryce Dessner’s synths and guitars as effective when gossamer as when layered and/or washed in distortion, Scott and Bryan Devendorf’s intricate rhythms often understated yet integral.

With subsequent albums, starting with 2013’s Trouble Will Find Me and culminating with this year’s First Two Pages of Frankenstein, released in April of this year, the band moved gradually toward bleaker soundscapes and melodies and, in terms of lyrical stance, a pronounced sense of disillusion and resignation. One might say that the four albums released between 2013 and 2023 addressed mid-life, including the barbed equanimity and experience of anticlimax that often accompany it. Sonically, with exceptions, the band practiced restraint, expressive yet less ostentatious, resourceful but utilitarian. Melodies were contained, less hook-oriented; a world-weariness, occasionally tinged with dry humor, pervaded and often eclipsed the sets.

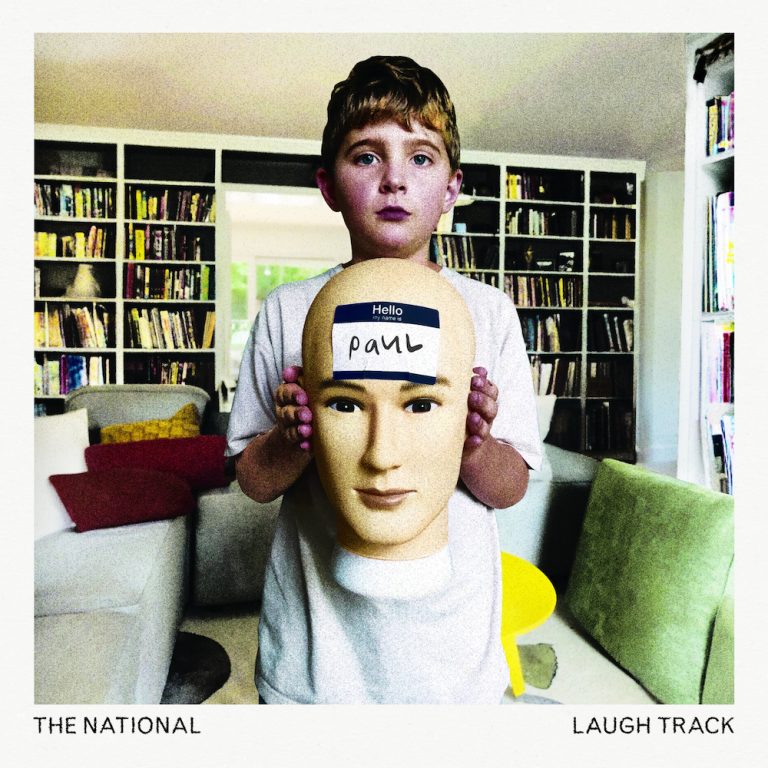

With Laugh Track, their 10th studio release and second this year, the band mostly continue on the trajectory they’ve carved during the last decade. Following the austere Frankenstein, the band seem relatively assertive, again wielding a broader range of sonics. Berninger’s vocal delivery is largely muted; the mercurial and even passive-aggressive eruptions of the 00s are all but gone; rather, there’s a downcast directness here, which at times is compelling in the way that self-revelation and truth-telling can be; at other times, such singularity seems glaringly reductive, a listener wishing for the metaphors, tortuous narratives, and volatile phrasing of earlier work.

On Laugh Track’s opener, the synthy “Alphabet City”, Berninger is in familiar territory, addressing the ennui that can ensue when a relationship is falling apart; “I’ll still be here when you come back from space / I will listen for you at the door”. The band navigate a fluid mix of rhythms and catchy embellishments. “Dreaming” features a simple yet enrolling melody, soundscape replete with punctuations, the Devendorfs trading notable accents. Berninger’s funereal delivery on the title piece, contrasted with Phoebe Bridgers’ airy performance, brings to mind a cross between Leonard Cohen, Peter Gabriel, and Bowie circa Black Star. The song epitomizes the band’s post-High Violet perspective: a couple drifting into parallel lives, Berninger mired in ambivalence. Loss is his self-fulfilling prophecy, dejection his habit, regret his trademark.

Unfortunately, some tracks fail to translate. On “Deep End”, Berninger embodies that sense of impending crisis that has become one of The National’s thematic calling cards. Melodically, the sketch drags, though Berninger’s voice is intriguingly battered by guitar strums and a busy drum part. “Weird Goodbyes” is all-too-familiar lyrically. “I don’t know why / I don’t try harder”, Berninger sings, voicing the shadow of his slacker side. He laments his dearth of motivation but doesn’t seem inclined to make more of an effort. Musically, the song is alluring for its welter of synths, its rising and passing ornamentations, though overall there’s a lethargy that pervades the mix. “Hornets” lacks melodic development, Berninger’s voice bobbing in a wash of surprisingly tepid sonics.

That said, the brisk feel of “Coat on a Hook” is revitalizing. Berninger’s weighty baritone is aptly juxtaposed by spry piano notes and buoyant percussion. Rosanne Cash’s guest vocal on “Crumble” exudes a refreshingly spontaneous vibe. Closer “Smoke Detector” recalls “The System Only Dreams in Total Darkness” (from 2017’s Sleep Well Beast and one of the band’s best takes from the past decade), serving as a memorable conclusion to the sequence. Built around a repetitive guitar lick that segues into a battery of pyrotechnics, Bryan Devendorf’s pounding drum part, and Berninger’s agitated sprechgesang, the track sounds futuristic, dystopian, anti-confessional. Perhaps the band will pick up here when they begin working on their next release.

While Frankenstein was introverted in tone and presented few overt hooks, the set succeeded in conjuring the bleakness of gathering age, the dawning awareness that one’s attempts to construct a stable identity have been in vain. In this sense, Frankenstein documented Berninger’s confessional/diaristic bent taken to its predictable conclusion. On Laugh Track, however, Berninger struggles for lyrical and vocal verve, even as the band offer frequently cogent reinterpretations of their playbook. Unfortunately, self-deprecation, cynicism, and melancholy at some point cease to be reliably fertile sources, particularly when you’ve founded a career on them, as Berninger has done. Many artists face this juncture: what was seminal tilts toward repetitiveness. The radical becomes cliché. The signature devolves into the formulaic. Hopefully, going forward, The National can plumb fresh territory, propelled by urgency and an ache to reinvent themselves.