The Kuleshov effect is a cinematic experiment that aligns the image of a man’s expressionless face with a series of images. It occurs not within the tangible space of the material, but within the spectator’s head – the observer attributes specific emotions to the man’s facial expressions depending on the images he’s aligned with. Following the image of a grave, his expression was read as grief; connected to the image of a naked woman it was seen filled with desire; and when intercut with a bowl of soup observers thought he looked hungry. What the experiment proves is that humans attribute their own emotional understanding to any image they come across, with interpretations based both on association but also their own predispositions. Remember that.

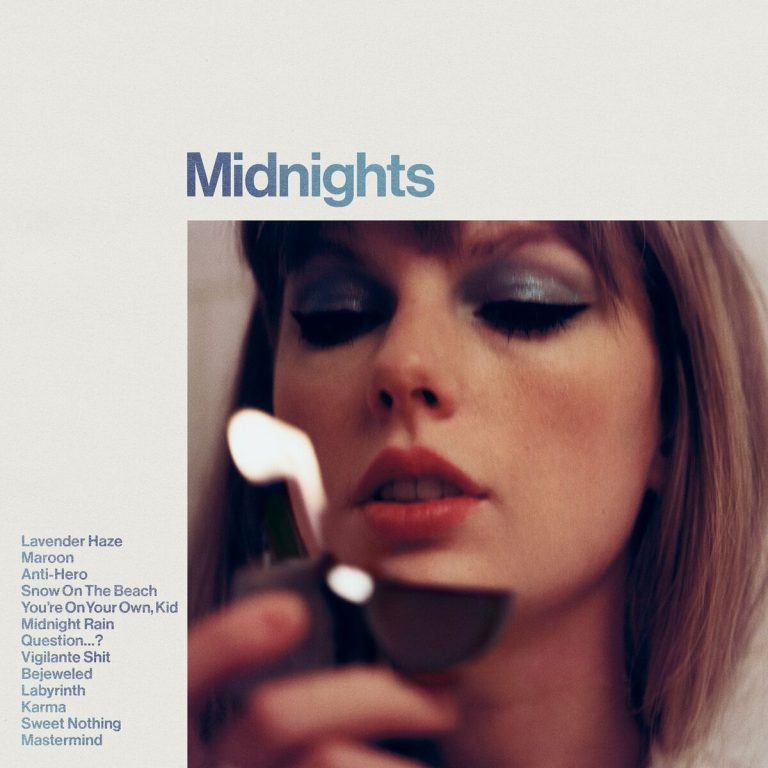

The image of Taylor Swift staring into the flame of a lighter on the cover of her 10th album, Midnights, remains enigmatic. Swift seems relaxed, in contrast to her stark eye shadow and striking signature red lipstick, gazing into the flame. It’s possible to read this image as a reference to Swift’s beloved Game of Thrones, when the mad king Aerys Targaryen bellows his last words: “Burn them all”. Another reading could tie it to the deeply spiritual process of ‘Trataka’, or ‘flame-gazing’. Associated with yoga, ‘flame gazing’ is a meditation technique used throughout many religions and rituals, and is even associated with banishment rituals. In one reading, Swift tears down every outer aspect that holds her back, in another, she faces her inner self – in both, it’s a process of transformation.

Yet a third position could be that the imagery combines the iconic cover of Hole’s Live Through This with David Lynch’s eerie exclamation “Fire, Walk with me”. Remember this.

The multiple readings of the Midnights cover reflect Swift’s larger persona in the public eye: much of her work has been shrouded in a dense fog of codified mystery, with hints and allusions abounding over the course of her many albums, lyrics and symbols interconnecting, fleshing out specific events or experiences, at times providing additional angles or sudden bursts of clarity before obscuring the image even more. This has led many analysts of Swift’s work to resolve to wild speculation and intricate theories, which the star at times seems to encourage, but mostly meets with a graceful, subtle smile: next question, please.

To be clear: with Midnights, she doesn’t lift the veil or solves the mysteries. Instead, she provides her most personal, darkest and intimate insight into her inner workings, draped in beautifully subtle nocturnal RnB. Following the exploration of mythologies (personal and fictional) of the dual monoliths Folklore and Evermore, Midnights marks her most mature and direct statement, clarifying that all her prior personas aren’t fiction, but facets of the very same person that grapples with uniting those elements into a whole.

Fashioning the overall sonic aesthetics of her new project on Lover’s standout tracks “False God” and “Afterglow”, the majority of the album uses a pop blueprint to construct Swift’s own take of modern soul and alternative RnB, ‘stripping down’ both metaphorically and figuratively. In this regard, this is reminiscent to David Bowie’s approach of creating what he deemed “plastic soul” on his record Young Americans – and really, once you compare the two albums’ covers, the reference point becomes clear. During this era, with tracks like “Somebody Up There Likes Me”, “Fame”, “Who Can I Be Now” and “Win”, Bowie fully let go of his Ziggy persona to observe his own modus operandi and relationship with living in the limelight. There’s a humble grace in both records, and a reliance on nocturnal, late night energies to confront those themes. And Swift is clear about her intentions when she, unambiguously, revealed Midnights to be a concept record that chronicles 13 sleepless nights over the course of her life. Where many had to speculate and analyze her two prior records to find hidden meaning, here it’s all up front: you get the unedited Taylor.

Yet that doesn’t mean there isn’t a plethora of codes and symbols that fans will likely spend hours analysing. One of those can be found in the first line and very title of the album: the idea of the midnight seems to be more figurative, describing a moment of deep change. Swift has used the image of New Year’s Day to signify personal rebirth before, most prominently in the lyrics and music videos for Reputation, but what exactly her Midnight means is more complicated.

It seems to be moments of great emotional turmoil, of introspection, of being isolated and without guard. This can be clearly observed on “Lavender Haze”, the album’s opener, where the commencing “Meet me at Midnight” line is conspiratorial and addresses her partner and audience. She then discusses the public opinions directed at her sexual and romantic life choices: “All they keep asking me / Is if I’m gonna be your bride / The only kinda girl they see / Is a one-night or a wife”. Over a background fit for an FKA Twigs track, Swift compares her own desires to the “the 1950s shit”, the conservative ideals she’s confronted with.

The next track, the highlight “Maroon”, chronicles an amour fou in a lurid fashion. Swift references a variety of her previous songs, tying together disparate elements for the first time. There’s the titular colour, which Swift associates again and again with the colour red (there’s red wine, lips, flushed cheeks, roses, rubies) and which harkens directly back to the title track of… well, Red. There is a reference to “The One”, which connects it to the character on the opening track of Folklore, as well as the flushed cheeks of “Illicit Affairs”.

But the most substantial reference is the specific setting of New York, a somewhat mythical place to Swift, which on 1989 was the symbol of a newfound freedom, but which since Reputation has been associated with a secret affair and emotionally crushing loss (there’s countless references – among them “Cruel Summer” and “Cornelia Street” – but most nakedly painful is this line from “Hoax”: “You know I left a part of me back in New York / You knew the hero died so what’s the movie for?“). To Swift, New York seems to represent a feeling, one which is directly tied to a person and a falling out that lingers emotionally: “And I wake with your memory over me / That’s a real fucking legacy to leave”.

The song is interesting both because of its lyrical references and the use of electronic guitar, played with an E-Bow. Not quite shoegaze, it is reminiscent of Interpol’s “Take You on a Cruise” or R.E.M.’s “Be Mine” – more Beach House than My Bloody Valentine. The single note that extends and slowly oscillates up and down works as embodiment of this lingering pain, which by now cuts through different songs and albums. It’s strange that producer Jack Antonoff decided to mix the notes into the background instead of having it come crashing down in the foreground, which would further manifest the emotional violence Swift verbalizes in lines such as “I feel you, no matter what / The rubies that I gave up”. Because, let’s face it, maroon is also the colour of dried blood – and Swift is speaking of hurt and decay when she sings of “The mark they saw on my collarbone / The rust that grew between telephones”. It’s borderline traumatic to listen to, maybe the pop song of the year.

Another track that will endure due to its violent honesty follows in “Anti-Hero”, where Swift faces self-hatred and depression head on, imagining herself surrounded by the people she’s ghosted and a scheming family that is only after her inheritance. The scar on her collarbone returns here as she imagines herself a giant monster with a pierced heart, unable to die. There’s faint irony here, but also fatigue as she repeats the signature chorus: “It’s me / Hi / I’m the problem, it’s me”. This connects with much of Swift’s self-reflection chronicled in the documentary Miss Americana, where she discusses her vast insecurities, but it also points out her standing in the music business, where the ‘family’ of surrounding industry players see her merely as a money-making annoyance. The midnight here stretches into the afternoon, further characterizing the moment as a feeling, as Swift goes to war and shock imagery abounds: “Did you hear my covert narcissism I disguise as altruism like some kind of congressman? / A tale as old as time / I wake up screaming from dreaming, one day I’ll watch as you’re leaving and life will lose all its meaning / For the last time”.

Thankfully, the darkness lifts a little with “Snow On The Beach”, which introduces a very interesting sonic inspiration. The minimalist classical background has hints of modern composers like Philip Glass and Steve Reich, with the short up-and-down of pulled strings looping as the vocal line extends over it. It’s incredibly cinematic, with the use of bells also introduces a somewhat wintery nuance, but the orchestral bed drives the song and makes it softly avant-garde in a manner similar to Bowie’s equally Reich-inspired “Weeping Wall”. Much has been made of the Lana Del Rey feature here, which is already being memed as inaudible – if anything, Del Rey’s voice adds a subtle shade of melancholia, contrasting the pure happiness of the miniature love story the lyrics chronicle. It indeed does feel like, as Swift points out, a moment from a movie.

This theme that into “You’re On Your Own, Kid”, where Swift returns to her hometown, attending what could be read as a homecoming dance only to find her friends ignore her and have moved on. After referencing the ‘Daisy’ persona from Reputation‘s “Don’t Blame Me”, Swift imagines herself as Carrie in the climactic moments of Brian De Palma’s interpretation as the scene turns apocalyptic: “From sprinkler splashes to fireplace ashes / I gave my blood, sweat, and tears for this / I hosted parties and starved my body / Like I’d be saved by a perfect kiss / The jokes weren’t funny, I took the money / My friends from home don’t know what to say / I looked around in a blood-soaked gown / And I saw something they can’t take away”.

As on the first two tracks of the album, the musical composition on “You’re On Your Own, Kid”, with its plucked guitars and subtle synths reminiscent of The xx, hides the emotional darkness quite well, and opens many questions. In a way, it feels like Swift is using pop music to cast a shadow over the brightly illuminated truths within her lyrics on Midnights. Maybe this polarity is not so much a contrast but – similar to the industrial and noise elements on Reputation – an open admission, like a wizard who will introduce his show by exclaiming his work is illusory, but still distracting the audience during the process to alleviate the performance.

Swift portraying herself as Carrie puts into sharp focus who the “monster” in “Anti-Hero” is, illuminating a worldview where women are driven to violence and madness by a world that confronts them with brutality until they break under the punches. That’s where the earlier mention of Courtney Love and Laura Palmer makes a lot of sense – the dark side of the homecoming queen has been a classic staple of modern American pop culture. But in Swift’s equation there is no Bob and no Kurt Cobain; there’s just the very real loneliness of a person constantly bombarded with her own reflection, and her attempts at finding new personas to confront this isolation, which shift and mutate.

As an example, the image of cold blooded vengeance extends to “Vigilante Shit”, where Swift takes the role of Catwoman, all lascivious eyeliner and dressed for revenge. It’s the album’s most minimal track, all quiet anger with its hushed beats and subdued synth lines. Funny enough, the closest sonic reference here is Talking Heads’ “Listening Wind”, which imagines a very different type of revenge and a different kind of vigilantism. This familiarity shouldn’t be read as direct reference, but the similarly eerie-yet-beckoning atmosphere showcases how there is a thematic basis within the emotional core message.

There’s another link here: “Vigilante Shit” is one of multiple appearances of Zoe Kravitz’s presence (the others being her co-credit as writer of “Lavender Haze” and bonus-track-title “High Infidelity” riffing on her show High Fidelity). The actor and the songwriter reportedly quarantined together during the lockdown and Swift later praised her friend’s interpretation of Selina Kyle in The Batman – and the subtle but clever parallels (the cat’s eye, the need for revenge, the double identity, the vigilante character) are too numerous to not work. Kyle can be lined up with Palmer; Carrie and Love as mythical American women who are being demonized for being maladjusted and fighting back against a system that is all too ready to bend them until they break. Their demons are, in a way, manifestations of the structure they reside in – and while Palmer, Carrie and Kyle have Twin Peaks, Santa Paula and Gotham respectively, Love and Swift have LA and New York. This is where the cover art of Swift staring in the flame becomes much more than just an image – to banish the demon or to burn it all down?

If this seems all too transparent, the rest of Midnights‘ mid-section is much more cryptic. There’s “Midnight Rain”, whose melody seems to directly reference that of “Call it what you want” off Reputation, contrasting two different yet somehow reflecting relationships. There’s “Question…?”, which either has Swift observe how the public react to her love life or actually confront a very real lover who seems to play down physical interactions. There is the throbbing “Bejeweled”, which lyrically seems both so specific and odd that it almost has to reference true personal interactions (“Don’t put mе in the basement / Whеn I want the penthouse of your heart” feels so clunky, it simply has to be a reference only the recipient of the track can understand), while it also mirrors Swift’s self-characterization as a mirrorball on Folklore. These are the songs that Reddit will go to war over, attribute references and party-photos onto, getting busy like Charlie on his whiteboard.

But clarity is just over the horizon, as “Labyrinth” returns to the images introduced in “Snow On The Beach”, chronicling the moments Swift finds herself falling in love. Likely about her first encounter with long-time partner Joe Alwyn, it’s a beautifully simple song that is complemented by shimmering beats, a hint of church organ and subtle guitars.

This is followed by what is the second immediate masterpiece next to “Maroon” in “Karma”. I won’t even dive into the entire lore behind the song’s title (which may-or-may-not be a shelved pop-punk album from peroxide-era Swift), and instead focus on marvelling about how Taylor Swift… has released a chillwave song. With its disintegrating intro and warbled synths, warm beat and nuanced highlights, the song would fit onto a Neon Indian album or into the 100PercentElectronica label canon. Once more, the bright and colourful music hides a darker theme, which sees Swift address a particular foe (Scooter Braun?) with confidence and the knowledge that karma rewards those with clean consciences. It’s the one big singalong song of Midnights, her first foray into chillwave (!!) and deserves to be counted among Swift’s top 10 tracks.

Equally wonderfully but vastly more subtle is “Sweet Nothing”, an organ-led ballad that invokes the imagery of Abel Ferrara’s 4:44: the last day on earth is here! “They said the end is comin’ / Everyone’s up to somethin’ / I find myself runnin’ home to your sweet nothings / Outside, they’re push and shovin’ / You’re in the kitchen hummin’ / All that you ever wanted from me was sweet nothin’”. It doubles as apocalyptic fairytale, in which the small luck of love outlasts the crushing chaos of annihilation and the troubles of the music business, which are left outside the door of domestic bliss. It’s also where Swift fully embraces her cancer moon, if you believe in such things: “The voices that implore / ‘You should be doing more’ / To you, I can admit / That I’m just too soft for all of it”.

It’s followed by the record’s defining statement, within “Mastermind” where Swift presents herself as a chess-playing manipulator who, with great skill, weaves a web around a love interest, until the trap snaps shut: “You see, all the wisеst women / Had to do it this way / ‘Cause we were born to be the pawn / In every lover’s game”. It’s a luxuriously sexual and clever song, in which Swift hides her most striking admission yet: “No one wanted to play with me as a little kid / So I’ve been scheming like a criminal ever since / To make them love me and make it seem effortless / This is the first time I’ve felt the need to confess / And I swear / I’m only cryptic and Machiavellian / ‘Cause I care”.

Those lines are so significant because Swift reveals the blueprint to so much of her cryptic communication and strange approach to interconnecting lyricism and writing. It’s self-psychoanalytical and opens a lot of boxes. Swift enjoys that so many fall for the Kuleshov effect, that this game she plays with her audience of interconnected themes and ambiguous images and personal references leads to wild theorizing. Yes, the song could be all about a lover, but it could just as well be about how she has managed to capture the attention of thousands of fans who find themselves pointing at the whiteboard, setting up strings, maniacally ranting about Alwyn, Kravitz, New York and the color red, all while Swift just smiles and sets up the next riddle to crack. It’s a beautiful bow to an album which, at 44 minutes, is not a second too short or too long and doesn’t feature a single song that seems worthy a skip.

There’s one question burning under the nails: does Midnights present us with the real Taylor teased at in “Look What You Made Me Do”? We definitely never got closer. Swift at times relies on the alternative RnB effect of filters that turn her voice androgynously low. Contrasting the anti-industry theme of cyborgs, which reverberated throughout Reputation’s music videos and songs, this aesthetic trick highlights how Swift uses her art to transform herself into characters: she transfigures the truth into a cryptic labyrinth, where words can have double meanings. Songs can address people, but also situations or groups that significantly impact her.

Likewise – and this is where the whiteboard comes out (take note, Reddit) – Midnights could be folded in on itself on “Question…?”, aligning “Lavender Haze” and “Mastermind”, “Maroon” and “Sweet Nothings, “Anti-Hero” and “Karma” etc. to reveal additional meaning to those themes: a dual existence of the musician as both Swift and as Taylor, of the person and the persona. Thus, Swift has finally done what Folklore hinted at: come up with a pop album that still fits the mainstream but includes hints and tastes of the underground – even if just measured ones. Her compositions here are humble and minimalist, but the additional elements often feel poignant and elevating. Likewise, her lyrics are clearly personal, but also include darker references to drugs and genre film, simultaneously addressing her past work to clarify meaning.

Yet some of those lyrics include metaphors which still feel oddly out of sequence, such as the “cat eye sharp enough to kill a man” or “the penthouse of your heart”, which has already prompted the meme factory of TikTok to find their cringe. These moments feel personal to Swift, as they lack the polish of her more intuitive writing.

Likewise, the mid-section of the album isn’t as brave in its musical experimentation as its first and third acts, sadly revealing that Midnights might have the hurdle of not bringing in any new fans to the camp. Much of the latter can be attributed to collaborator and producer Jack Antonoff, whose aesthetics are still much more squeamish than those of the similarly pop but vastly more adventurous Dave Sitek. When Swift introduces those stains or glitches – elements of imperfection hinting at a darker subtext and a ghost within the house – Antonoff delegates them to the background while, if they were brought to the foreground, would come crushing down and demand tears and rushed heartbeats.

Sometimes Antonoff seems to lose that emotional balance, resulting in measured response from the audience. And, judging from the initial online response, the record seems to be shaping up as the most divisive in Swift’s career, besting the gorgeous-but-initially-hated Reputation. Yet, just as with her sixth record, the stark polarity in responses magnifies that Swift has made something that is directly reflecting her edge as much as her intellect. Which, once more, sharpens the comparison to Young Americans: as many musicians turned online to write their thoughts on David Bowie after his passing, the vast majority of pieces singled out the icon’s 1975 album as the misunderstood and highly influential favourite of many.

It’s clear that every listener will read Midnights in their own way – the record is simply too rich to function as background soundtrack. It’s a blistering experience that demands commitment, concentration and deep engagement – it’s an artist banishing their demons. It resides among the very best of Swift’s output and could end up mythical, especially to those who try to crack the cryptic codes. Nothing about Midnights is cheap and its expansive nocturnal glamour will slowly outlast many pop albums. We all turn towards the light of the moon, when staring into the flame becomes exhausting.