A group of people, wailing, dancing – dancing! Excitement and bright colours, which give way to the bright lights, the overexposed face of a beautiful, young, blonde, woman.

The scene shifts: as the woman lies down in bed, snowglobe falling to the floor and shattering, her cherry red lips form one word: “Forevermore”. Fade to black…

A car crash! Laughter, tears, flashing lights, polaroids and smeared mascara. A woman in trouble in the City of Dreams. The past is always brighter than the present…

2014 was everyone at their very best. Opportunities seemed everywhere! David Bowie had just released a new album the year prior. Obama was still president, and widely beloved. Drive was everyone’s favourite movie and Man of Steel suggested a bright, more authorial future for blockbuster cinema. And Kanye West was still fun. In other words: the United States of America was overcoming its 9/11 trauma, slowly but gradually, indulged in the search for a new popcultural canon.

The 80s were back big time, and art indulged in the monolithic and iconic, with bright colours and shining heroes marking a new national confidence. Somewhere here, airport doors slide open to reveal: a beautiful, young, blonde woman, all red lipstick and bright smiles. The next Marilyn – the next Madonna. The world was waiting for her! Welcome to the fairytale! Welcome to New York! Welcome to 1989!

By 2014, Taylor Swift was already larger than life. There was the cataclysmic moment during the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards, where Kanye West transformed the stage into a wrestling promo. There were the constant yellow paper headlines on her personal relationships, chronicling every which step she took with friends and lovers.

And there was Red, an incredibly ambitious singer-songwriter album that embraced arena rock, indie pop, country-folk and bubblegum bangers. Swift could have gone anywhere and done anything – the world was hers to take, and the young songwriter was eyeing a move to London! But plans have a way of just not working out. Or, as in this case, something better comes up.

Finally meeting and striking a close friendship after mutual associates babbled on about how alike they were, Karlie Kloss convinced Swift to settle in New York instead of the United Kingdom. The move didn’t just provide a change of scenery, it also created thematic motives which, from then onward, would weave through Swift’s body of work as a recurring red thread.

And it birthed 1989, Swift’s most iconic, best-selling album: a reframing of the singer as Madonna-like pop queen who would shapeshift chameleon-like with each project and inhabit a myriad of forms, all characterised by her diaristic perspective. It would also spawn a newfound confidence in a cryptic back-and-forth with fans, marked both by criminal honesty and constant ambivalence.

Nowhere is the persona of this new era more palpable than in the opener “Welcome To New York”. A twist on both Bruce Springsteen and Cyndi Lauper, the song has Swift introduced to her new hometown, a constant opportunity for new experiences. Harbouring a vague Broadway quality, it has been read as a Wizard of Oz-style introduction of scenery – kind of an absurd reading, considering Ariana Grande embodies the Dorothy motif more consequently in contemporary pop. And while some reviewers read it as Swift exploring the Cinderella trope, the evolution of the record and Swift’s development over the coming years offers a more daring interpretation to the song – and 1989 as a whole. The euphoric (and possibly naive) perspective on New York resembles Betty’s introduction to LA in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Like Betty, Swift is the rural outsider that finds herself wowed by the bright lights and fresh faces of the big city: “Everybody here wanted something more / Searching for a sound we hadn’t heard before / And it said Welcome to New York / It’s been waiting for you!” But behind the facade, something darker is hiding. And like Betty in Mulholland Drive, there are hints that Swift isn’t as innocent as the somewhat naive demeanour suggests – as she observes herself: “Everybody here was someone else before”.

“Welcome To New York” has occasionally been dismissed as a lesser pop song on 1989, when in reality it is a rich tapestry of double-entendre and references that would spawn years of fan theories and re-interpretations. “New York” isn’t just the city landscape – the term becomes a stand-in for Swift herself in the years that would follow (from “False God”: “Staring out the window like I’m not your favourite town / I’m New York City / I still do it for you, babe” – from “Hoax”: “You know I left a part of me back in New York / You knew the hero died, so what’s the movie for?”). It’s not even cryptic the way she uses the city to redefine herself: “Like any great love, it keeps you guessing / Like any real love, it’s ever-changing / Like any true love, it drives you crazy”.

There is one notable line here whose importance has shifted throughout the years: Swift’s first embrace of queerness in her writing. “And you can want who you want / Boys and boys and girls and girls”. Side-eyed up to this point as a possible conservative due to her focus on traditional relationship dynamics and Christian imagery, this throwaway line burst the bubble and showed Swift’s liberal leanings and support of the queer community one year short of the US Supreme Court’s approval of gay marriage. In 2014, gay rights were still uncertain in the States, and it was Swift’s first (codified) political statement. On the flipside, it would also spawn theories of possible queerness that overtook parts of the fandom. This, in turn, would lead to contrasting readings of the muses behind 1989 – from Harry Styles to Dianna Agron.

Swift recently suggested that much of the fan speculation was nonsense, but the phantom of those theories still looms large. This is where New York becomes a kippfigur, a tilting image that can be two things at the same time, like the drawing of the young maid and old woman. Yes, New York was the backdrop for Annie Hall and When Harry Met Sally, but also for Taxi Driver and, a little later, Cruising. It spawned Is This It? as much as Suicide. Every fairy tale has its shadow lurking, just as LA has its Man behind Winkies. And our protagonist? She has Starbucks Lovers.

Swift directly embraces this dual-form in “Blank Space” – a song that famously features the misheard lyrics that even her mom got wrong. Here, she works through the spectre of the jealous girlfriend who reacts in violent outbursts and pairs “Cherry lips, crystal skies” with “Screaming, crying, perfect storms”. Intended as satire, the song was read at face value, providing a blueprint for future endeavours. Reappearing throughout Reputation in similar form to “Blank Space”, Swift has taken a more ruminative approach to reflect on vindictive urges and the ‘toxic’ archetype on Lover with “Afterglow” and “False God” and on Midnights‘ “Anti-Hero”. Like so many songs on 1989, “Blank Space” saw Swift learn that ambivalence suited her well, placing her songs in a malleable world where details would both be suggested, yet remain wholly abstract at the same time, inviting fans to participate on a wild chase down the rabbit hole. This is also true of another recurring thematic parallel with Mulholland Drive: car crashes.

No, Swift hasn’t read JG Ballard’s novel Crash or watched David Cronenberg’s masterful adaptation as far as I know… or has she? Either way, the car crash here becomes a strangely psycho-sexual occurrence, a traumatic climax of relationship anxiety that marks the intersection of bodies and eruption of emotions. “Remember when you hit the brakes too soon? / Twenty stitches in a hospital room […] But the monsters turned out to be just trees / When the sun came up you were looking at me”, she sings in “Out of the Woods” (one of 1989‘s two collaborations with Jack Antonoff). “Style” – a song inspired by the Giorgio Moroder inspired synths of the Drive soundtrack – opens with the lines “Midnight / You come and pick me up, no headlights / A long drive / Could end in burning flames or paradise”, while “Wildest Dreams” starts on “He said / Let’s get out of this town / Drive out of the city, away from the crowds / I thought Heaven can’t help me now / Nothing lasts forever / But this is gonna take me down.”

This crash – or accident – returns later in her work (“Coney Island” eerily concludes “And when I got into the accident / The sight that flashed before me was your face / But when I walked up to the podium / I think that I forgot to say your name”), and Swift has since addressed the topic in interviews, most famously a radio broadcast where she referenced a deeply traumatic moment which occurred outside of the public’s gaze. Does it refer to her living through two of them in one day, or a snowmobile accident with Styles? Is it all the same just a metaphor for our tendencies to enter reckless, dangerous situations when aroused or in love? Swift herself concluded: “People think they know the whole narrative of my life. I think maybe that line is there to remind people that there are really big things they don’t know about.”

Working forward through 1989 and deciphering its meaningful references seems all too simple, before one by one contradictions and ambiguities appear. Where Red was often straightforward in alluding to its inspirations, on 1989 Swift dons a mask of consistent metaphors and plays with alter egos that reshape her autobiography. “Blondie”. Betty. All the same. And none of them. Which, as laid out in the case of “Welcome to New York”, exhilarated those fans who enjoyed weeding through the recurring imagery to focus on their own reading of her songs. But on the flipside, it tilted into direct antagonism and accusations of manipulative behaviour. To realise what toll this took on Swift’s image, one doesn’t have to look far into the past. When Swift poked fun at herself in the “Shake It Off” video, goofing in front of a monochromatic backdrop to suggest she’s all too human and would never be fit to win a jitterbug contest, it immediately was deciphered as conscious and malevolent self-trivialisation.

It’s easy to see what sparked this obsessive regulation of Swift’s public persona: 1989 is, as far as modern albums go, the most lasting and iconic pop record of its era – maybe the 21st century, really. The album is not perfect – “Bad Blood” is clumsily underdeveloped and gets the skip even from many diehards; “Shake It Off” is a little too ditsy in its wholehearted mainstream appeal; and the album’s second half isn’t as wholly iconic as the first – but it manages to supply almost constant stimulation and delivers memorable moments in the dozens.

Some of that is due to the clever writing and the immaculate production Max Martin and Shellback crafted surrounding those blueprints. But most of all, credit has got to go to Swift’s incredibly emotive, suggestive and – at times – lascivious delivery of her lyrics. Yes: this is possibly Swift’s strongest showing as a vocalist, delivering pain, sadness, euphoria, flirtatiousness and goofiness. Revisiting her performances in “Style”, “Wildest Dreams”, “This Love” and “All You Had to Do Was Stay”, it becomes clear that the singer poured her entire being into these performances, her voice at times shaking. The recipe to the record’s success was that it captured a singular moment of inner strength and confidence that, simultaneously, communicated all the complex emotions that go into a human being.

The album’s greatest crime, thus, was that it abandoned its best composition as b-side: “New Romantics” feels like the ultimate thesis of this era, a lurid summary of youthful club-culture that has a chorus that resides among the best ever written, and it seems absurd “Bad Blood” and “Shake it Off” were chosen instead. “Wonderland” and “You Are In Love” are arguably also more essential and would have made the album flow better than “I Know Places” or “How You Get the Girl”, but those discussions are left to the great speculators of music history to mull over.

1989 hit all the spots – both in the hearts and minds of nations and the rewarding lists of Billboard charts and Grammy Awards. Swift had manifested herself as new American Goddess, and would ride this wave of pop-cultural relevance and popular iconography for a while to come. But somewhere lurked her shadow. Her very own Man behind Winkies, the spectre she had summoned on Red‘s “The Lucky One”…

In Mulholland Drive, there’s the moment when Adam Kesher meets a mysterious character with soulless eyes and a southern twang, simply named “the Cowboy”. This character – or entity – seems to possess a strange authority over the physical forces of our world that elude the artist, conducting the electrical light that frames their nocturnal get together. Like a character from Alice in Wonderland, he speaks in riddles and metaphors, surgically interrogating his opposite and finally asking Kesher how many drivers a buggy has. “So, let’s just say I’m driving this buggy. And, if you fix your attitude, you can ride along with me.” There’s a lot in those seemingly simple lines, but at the very heart, it suggests that even a successful artist at the top of the world has no power over their own creation: there is always somebody higher up the food chain.

It is not my job to recall what happened to Swift and her career in the years after the release of 1989 – at least not now, not here. This will come later! Suffice it to say, Swift soon found herself in a very different world, with identities splintering and realities shifting. In her own words: “I’m sorry, but the old Taylor can’t come to the phone right now. Why? Oh, ’cause she’s dead!”

What matters is this: Alice went from Wonderland on through the looking glass. Betty transformed to Diane. And like that, Taylor Swift’s world – and as a consequence, her imago – was shifted. And nothing was quite like it was before – the fairytale-like forevermore turned into the gothic evermore. The snowglobe shattered, as a realm of outsides (the streets and clubs of New York) became a singular inside (a walled off bedroom, with its sole resident the blonde representation of a nation). All subsequent records would bear witness to this shift, this loss of innocence and new interrogation of psycho-analysis. This is the girl!

And so, here we are, with Taylor’s Version. The re-recording – or rather, revisitation – of the defining moment in Swift’s career, impossible to forget all of the above. Recorded a little while ago, the album is the latest in the musician’s quest to reclaim her catalogue and, once again, frame the past through the present in her own image. This includes a ‘prologue’ that has already caused much fire in certain parts of the fandom. Yes, it (seemingly) does away with some pesky rumours, but some queer fans suggested it also communicated an inherent othering to romantic and sexual desires outside of the norm.

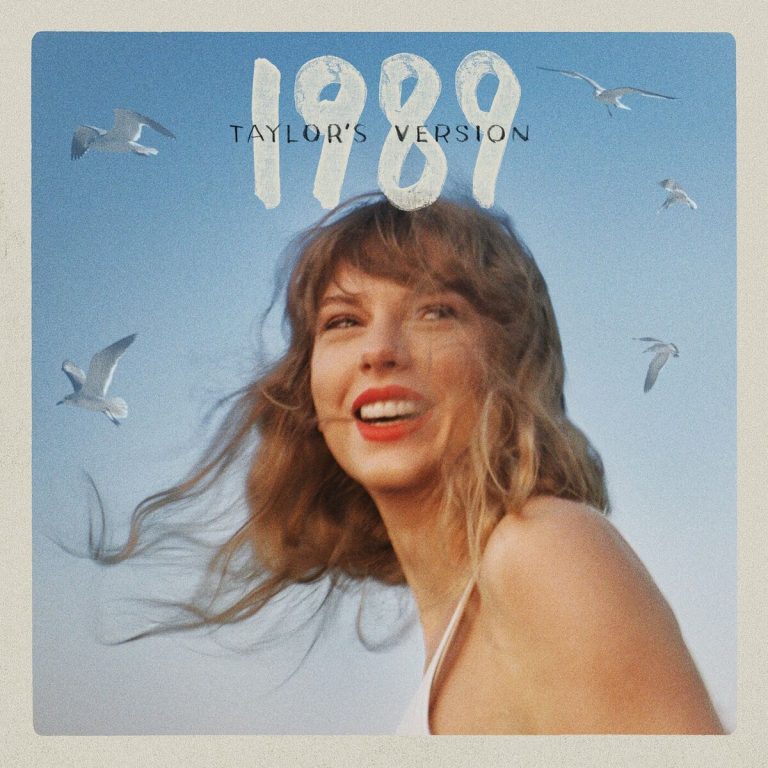

Then there is a truckload of physical versions of the release that slowly trickled into the merchandise section, all with different artwork (none of it as iconic as the classic polaroid of Taylor in red lipstick and seagull-sweater), unique colour-schemes and bonus content that caused wide derision on fan platforms. And I won’t even dip into the many discussions surrounding Swift’s private life the public indulges in – the point is that the youthful innocence and unabashed euphoria that marked 1989 is… gone, and has been for a long time. In its place is a kaleidoscope of memories that spawned from those years, which in turn informs this revisit to the past. Red (TV) presented an added layer of maturity and wistfulness – a dialogue of sorts between the very young and very mature Swift. Would this also work for its successor?

In a way, 1989 (TV) very much feels like a remake – more so than Red (TV) did. Christopher Rowe, who produced previous entries of the Taylor’s Version project, is joined by Antonoff, which results in much sharper edges than on the original. Synthesizers seem to occasionally fade into the back, with beats being a little edgier in the foreground. Most of the songs follow the same structure with very little change, but there is one overwhelming difference to the original that stands out: Swift’s vocals. No, not a single note is off – to a fault. Swift marches through her performances in even tone, rarely expressing emotions as fervently as on the original version. Her voice never quivers, rarely flirts, won’t dive into pain or grant a smile. She performs these songs like they belong to somebody else. When she dives into the “some other girl”-echo on “Style”, she merely hits the notes, where on the original her voice sounded like she was actually expressing held-back resentment. “Wildest Dreams” completely omits the pathos that lifted the original to become one of the great current day pop ballads. “All You Had To Do Was Stay” evades the cocky breathlessness that made the previous so charming. Charms are hard to find in this new version – with the omission of “This Love”, which is rewarded with an added layer of ambient glow, making it at least a little charming, but nonetheless not better than the original.

This leaves the “From The Vault” tracks all the more vulnerable, as they are tasked with carrying the project. Indeed, all five are nice, although they open more questions of the Swiftian Rubik’s Cube than they resolve. Allegedly conceived during the time of 1989, and resembling the album’s broad aesthetics, they are closer in tone to Midnights, which surely is going to open up a lot of speculation. “Slut” is a brittle synth-pop ballad that sports an incredibly strong melody, sporting a genuinely vulnerable vocal performance that the rest of 1989 (TV) so sorely lacks. “Say Don’t Go” has an even stronger blueprint, with its heart-wrenching, longing lyrics and an incredibly memorable chorus. “Now That We Don’t Talk” spins around a lost love or bruised friendship and reduces Swift’s vocals to a low whisper, fighting on against the falsetto of the refrain, all the while arpeggiated backgrounds bubble on like fluttering bursts of club lighting. Thematically, it almost seems more of a reflection on the era of 1989 than a product of the same time. “Suburban Legends” feels like a direct Midnights outtake, darker in tone and, sadly, too brief in its own interest, with the composition never rising beyond the familiar. Finally, “Is It Over Now?” is rich in bitterness, but can’t really find the right instrumentation – sort of like a less creative “Blank Space”, which never takes full advantage of the many twists and tricks Martin provided to that song.

The dissonance between those five emotional performances in contrast to the rest of 1989 (TV) should really open the door to more exploration. Are these new compositions on old lyrics, or current-day diary entries accompanying leftover musical ideas? Are these thoroughly old songs which Swift retrofitted onto her current day experiences? Or did she just afford these previously unreleased songs more care than the re-recordings, knowing full well that, in this case, the iconic status of the original would be impossible to match? There’s a lot to speculate on, but in the end, it doesn’t really matter, does it?

What remains is the refraction of time, the strange nature of memories and dreams and how our own perspective of the past, filtered through both the naivety of our younger self and the (possibly bitter) gaze of the now remain fractured. Mulholland Drive has Betty disappear and shift into Diane – an echo of a different person that projects itself forward onto the present to form a new future that is no longer coherent with the reality we think we know. The movie opens itself up to various readings, which all drift apart with the varying approaches to analysis: it could all be a dream, or the doing of sinister paranormal entities who rule above the plane of our human consciousness. It all could be the past that overtakes the present, or the consequence of all the charades and performances finally disappearing. Identity, in the film as in reality, is more defined by how we want to be seen than who we actually are when there’s nobody to watch – a red thread that weaves all projects of Lynch’s canon together, and an obsessive topic for Swift. She has, throughout her work, played with this multiplicity of herself, presenting a myriad of forms that can’t be united.

Thus it can only be logical that, when tackling her most sparkling past self, she can’t box in what made this album that entrapped (and still captures) the masses so unique. The consequence is equal to entering the “Club Silencio”: “No hay banda! There is no band! Il n’est pas de orquestra! This is all… a tape-recording.”

But this is not a failure in the least! In fact, if Swift had succeeded in replicating 1989 perfectly, she would have undone the spell of time that created it in the first place: that moment of the beautiful, young blonde woman that steps out of the airport gates, eyes wide, smiling from one ear to another. This is the girl! One can’t turn back time – one can only learn from it.

And so here we are, waiting for what’s to come next: bedrooms with sullen sheets. Rainy evenings in bars. Citizen Swift: So it goes! To speak in riddles, and to gaze towards the future: what does Alice lose, when she grows up?