Spencer Krug has always been a champion of using figures from mythology in his songs. You’ll find Midas on Sunset Rubdown’s Random Spirit Lover, while Apollo pops up on the band’s 2009 follow-up, Dragonslayer. It wasn’t until This One’s For The Dancer & This One’s For The Dancer’s Bouquet that Krug focussed in so intently on his fondness for figures from the Greek mythos. The 2018 double album (released under Krug’s now-retired Moonface moniker) mixed together material from two sessions, creating a (self-confessedly) bulky listening experience.

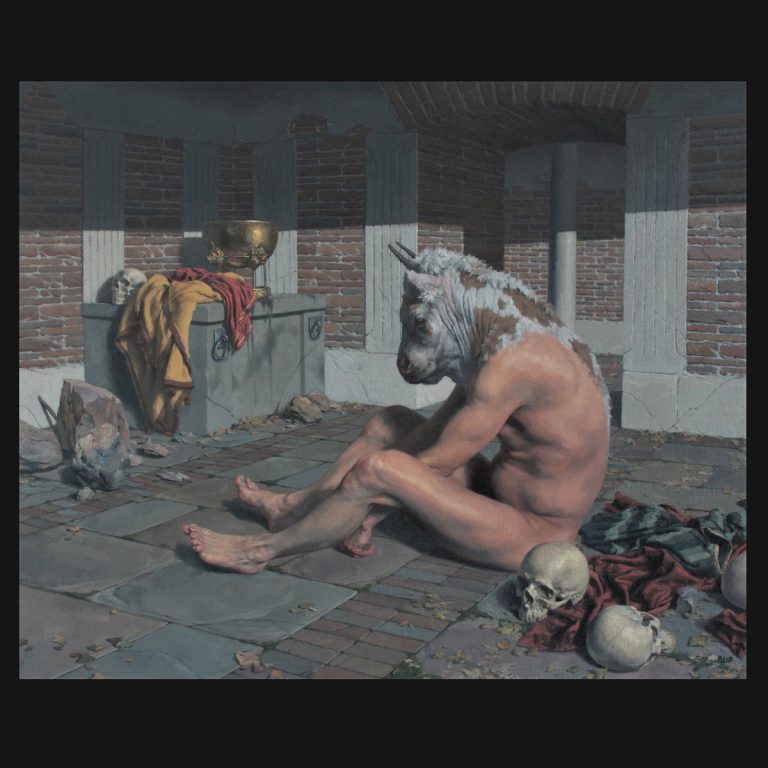

Many fans already decided to excavate each album, and thus each session existed on the internet as separate entities in some form or another. The “Minotaur Songs” (as Krug and his fans came to label them) were arguably the more cohesive of the two sessions, centring around the concept of the titular half-bull/half-man speaking out to those who have wronged him (and forgiving them, as the titles suggests), all voiced by Krug using a vocoder to “represent the minotaur in a voice that was not completely [his] own.”

The music was enough of a feature in itself too. Recorded and composed with percussionist Michael Bigelow in Breakglass Studios in Montreal in 2011, the two musicians utilized marimbas, vibraphone, steel drum, keys, and drum pads to create a marvellous backdrop of sound. Not only that, the music also felt like a natural continuation/conclusion of the instrumental studies Krug had done before, most notably his debut EP as Moonface, Dreamland, which laid out marimba and (“shit”) drum machines across a single 20 minute track.

Now, some four years after the original release of This One’s For The Dancer, Krug has released The Minotaur Instrumentals. Vocoder-voiceless, and boasting one extra track from the same original session, the “new” album puts the focus squarely on the music and all its intricate wonder.

It’s unsurprising to say that there are no surprises here, and for those already acquainted with the music, this will feel like familiar listening. All the instruments still weave together with majestic skill, Krug showing his penchant for layered melodies swirling around and between each other. “Knossos” still has its elastic lilt and bounce, “Theseus” retains its pomp and circumstance amidst all the rippling notes, “The White Bull” shimmers with a glass-like quality (and gives a little more time to the bookending ambience of the bowed notes), and “Daedalus” churns away like a machine full of cogs made by the titular character. Even without the voice that originally strung all these tracks together there’s still undeniable technical skill on display, and new listeners could get rewarding experiences from just trying to dissect each layer of the songs, if not getting immersed in the curiously hypnotic effects said layers have when stacked on each other.

For those familiar there are still details to enjoy, musical features that were before masked by the vocals: the flute-like keys accentuating the melody on “Knossos” and “Daedelus”; the oomph of the drum machine on “Minos”; and the descending melodical marimba touches at the end of “Theseus” that were easy to miss amidst the clamor of the original. This is an album mostly for the fans, but it’s those fans who will value these instrumentals so as to be able to hear the timbre of certain notes more clearly, appreciate the dexterous work put in, and add to their (already impressively large) catalogue of output from Krug.

The only new track here is “Send Me An Angel”, which is certainly interesting to hear on the first instance, but moreso for how inelegant it sounds compared to the other tracks here. With its stodgy stomp and contrasting flourishes of steel drum and marimba, it contains no sonic surprises; it only touches on something pleasant during its quieter moments of bowed notes and inquisitive keys. Perhaps it’s because it doesn’t have a missing voice playing in the head of this seasoned listener (I make no secret of the fact the original album had a profound effect on me and holds a forever-important part of my heart), but it does ring somewhat empty and feel notably less dynamic than the seven preceding tracks.

For such a hardworking musician though, The Minotaur Instrumentals feels like a perfectly fine victory lap, bringing back focus to music that may well have passed listeners by when it was immersed in its original context. While listening to these instrumental tracks sometimes feels like aimlessly exploring the Minotaur’s lonely labyrinth hoping to hear a voice, they still showcase the exemplary talent of Krug and Bigelow on their many instruments. Notes ricochet off the walls, paths circle back in on themselves, and like Daedalus’s original prison for the Minotaur, it’s an impressive construction but without the main character it does lose some significance.