I.

On 2nd November 2018, Spencer Krug released his final album under his Moonface moniker. Clocking in at 84 minutes, This One’s For The Dancer & This One’s For The Dancer’s Bouquet is a double album, bringing together two sessions recorded with different collaborators at different times across seven years. Instead of a simple Side A and Side B split of these two albums, Krug mixed tracks from each across the full final album, melding the “sun and moon” of the “same musical planet.”

Aware that the album is much too long for any reasonable person to consume in one sitting, Krug invites listeners to break This One’s For The Dancer apart; “I see each side of this four-sided album as it’s own little journey, a complete listen within itself, and easily enough for one sitting,” Krug elaborated in the press release for the album. Listening to the album on vinyl, this is an easy enough undertaking, each side of each record its own mini-album to consume at the drop of the needle.

Like I imagine many fans of Krug did though (deliberately or not), I tried taking in the album in a single sitting, going on the full 84 minute journey. Before long I began to heavily dislike the record, finding it much too bloated and meandering, and finding the jolting between sound worlds distracting from any consistent delivery of concise statements. Then again, it’s not like I wasn’t warned.

So I did another thing which I imagine fans did: I broke the two “albums” apart and started listening separately. Within a few listens of each side my appreciation began to blossom. Side B – consisting of songs that Krug described as having “a more traditional curve” and made in collaboration with drummer Ches Smith, saxophonist Matana Roberts, and former Wolf Parade bandmate Dante DeCaro – began feeling more stark and explorative of Krug’s own mindset through languid sax tones and delayed synth melodies.

Side A, however, became both the real takeaway and something completely enveloping for me. Consisting of just seven tracks running just shy of 37 minutes, this album was created in collaboration with Michael Bigelow. The music – a combination of marimbas, vibraphone, steel drum, keys, and drum pads – was written in 2011, and after a few months of writing words to go on top, was ready for the world. However, after a very last minute reconsideration, Krug pulled the album; it would be six years before he completed it, laying down new lyrics with an entirely new angle.

Musically, this album feels very much like a continuation of previous efforts from Krug, notably his debut EP, Dreamland: Marimba and Shit-drums, and his follow up album Organ Music Not Vibraphone Like I’d Hoped. The additional percussion on Dancer gives more depth and range to Krug’s sound, but it’s not the most interesting feature. Instead it’s the vocals and the lyrics. Not only does Krug give up his viewpoint to that of the Minotaur from Greek mythology, he also uses a vocoder to “represent the minotaur in a voice that was not completely my own.” (This also isn’t the first time Krug has heavily referenced figures of mythology: Samson, Apollo, and Midas have been name-dropped by Krug in the past.) Each track is titled “Minotaur Forgiving…” completed by a character from the creature’s life who played a part in him being trapped in his labyrinth alone. The album is an exercise in empathy from the monster’s perspective, and for months it was the only thing I listened to.

II.

In the latter half of 2018, I found myself spiralling into the depth of emotional and mental breakdown. I had spent months lying to and deceiving my friends, and even engaging in acts of infidelity. Through all of this I hurt my closest friends, oblivious at the time to the real and lasting damage I was doing. When my selfish actions came to a head in the final months of the year and all the lies started unravelling, friends broke away from me. Understandably, I was no longer welcome at social events or parties.

With everything around me suddenly and seemingly gone, I withdrew from all social aspects of my life and fell further into a pit of depression, convinced that each coming day would be the one where I finally took my own life. Though one or two friends kept me from falling completely over the edge by checking in on me from a distance, I spent the months isolated, lost, and unable to understand how I could have become the person I was and have carried out such horrible actions.

As is often the case with most instances of emotional trauma, time helped, but so did finally getting around to seeking out help from mental health professionals. They helped me begin to understand how my destructive thinking and my lifelong depression resulted in me being in the place I was. Looking back now, the biggest silver lining (because one always has to look for silver linings, even in tragedy) was that the events of 2018 led me to getting help, something which I put off all my adult life. I had existed until this point, convinced my own introspection and self-awareness of my mental illness was enough to treat it and live life normally.

In the lowest points of my life I have always used music as a form of therapy – sometimes the creation of music, but most often the immersion of myself in another artist’s work. During these final few months of 2018, I found myself listening to Side A of This One’s For The Dancer most of every day. On my walk to and from work I would disappear into the percussive lilts and sorrowful vocoder vocals, and while at work I would block out colleagues’ conversations, put my earphones in and type away while soundtracked by the pleas of the mythical creature.

It became both a comforting go-to for me to hear while doing everyday activities, but also a small immersive world to get lost in when I became too overwhelmed by my own thinking – especially when suicidal ideation took hold of me. This music was my escape, and also the invitation down a rabbit hole; it reignited my love of and interest in Greek mythology, and I quickly became obsessed with all things about the Minotaur. Before long, I had taken out every book in my local library which offered any mention of the creature, and was scouring through films, TV shows, or YouTube clips that referenced him – all in an attempt to better understand the devastating plea of the Minotaur. (Liz Gloyn’s enrapturing book Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture – which I only became aware of after writing this piece – also goes down this rabbit hole, albeit through a different and more studious lens.)

And this was because it was ultimately the plight of the Minotaur (as written and sung by Krug) that hooked me. He was a monster, and at that time I felt like one too; I was alone, much like he was; and most of all, he was offering forgiveness while I sought nothing more. I saw myself both in the music and apart from it. It was relatable, but also a form of escapism, a beautifully ineffable world to swim around in for 37 minutes, which I did over and over and over. In this immersion and the research into the Minotaur (that I took on at the behest of absolutely no one), I began to realise the true brilliance of this album; it wasn’t just speaking to me emotionally, it was also a masterful execution of original art.

III.

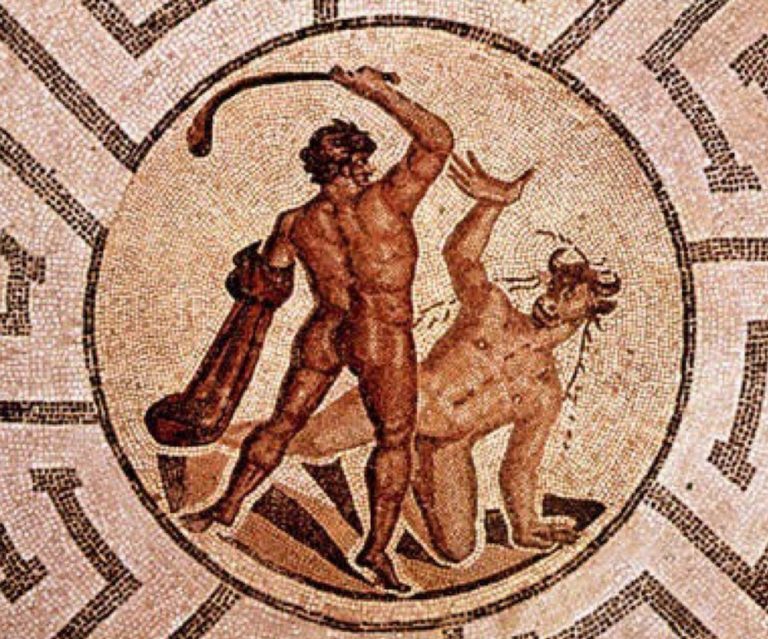

The Minotaur is something of an anomaly in the world of Greek mythology. He is a well known figure, image, and symbol, yet so very little is written about him, let alone anything from his perspective. Many anthologies of Greek mythology I came across mention him only in passing, and often mainly as part of the story of Theseus, the mythical king who slayed the Minotaur.

For those unfamiliar with the tale, it goes something like this: At his request, Poseidon sends King Minos a stunning white bull to prove the Gods have chosen him over his brothers to rule. Minos promised he would sacrifice the white bull in Poseidon’s name, but it turns out the God did too good a creation job, and Minos decided to keep the magnificent white bull for himself and instead sacrifice another regular and non-spectacular bull, hoping that Poseidon wouldn’t mind and/or notice.

Poseidon – being a God and all that – did notice, and was rather angry at this affront, so he decided to make Minos’ wife, Pasiphae, fall desperately in love with the white bull. All in the name of revenge. Unable to resist the white bull, Pasiphae goes to the master inventor Daedalus to request a large hollow wooden cow be built so she can trick the white bull into mating with her. Fast forward some months (and through the bestiality), and Pasiphae has given birth to a monster child, boasting the head of a bull and the body of a human. She named it Asterion after Minos’ father, but it would be more commonly known as the Minotaur.

Minos, ashamed and disgusted by this new child (and at the advice of oracles), goes to Daedalus and demands an impossibly large and complicated maze-like labyrinth be made in the city of Knossos to keep and hide the Minotaur. Once the construction is completed, there the Minotaur lives, wandering the halls aimlessly and devouring the seven Athenian boys and seven Athenian girls given to it as a sacrifice every nine years.

One year, at the point in the cycle when the sacrificial children are being rounded up, a young and confident Theseus puts himself up as one of the offerings, declaring he will slay the Minotaur and bring an end to the cruel rule from King Minos. On Knossos, Theseus is helped by Minos’s infatuated daughter Ariadne, who gives him a spool of thread to follow back so he may find his way out of the labyrinth. He ventures into the maze, meets the Minotaur, and slays him before returning to freedom.

This being Greek mythology, there’s a lot more detail than that mentioned above, what with each character having their own thing going on as well as having their own wildly deep backstory. Certain details also vary depending on your sources – some say the Athenian children were sacrificed to the Minotaur every seven years instead of every nine, for example – but I’m not an expert in the field, and am not trying to portray the story in any kind of scholarly way. This is just to give you the main gist, so as to understand the tale Krug has adapted, and which resonated with me so much.

IV.

To best appreciate Krug’s take, it seems worth first glancing at how the Minotaur is represented in other media. For the most part, the Minotaur is an easy go-to for an adversary, even if that means putting the Minotaur in apocryphal settings. In the 2012 film Wrath of the Titans, for instance, the hero Perseus kills a Minotaur that is stalking a maze outside Tartarus (as opposed to in the city of Knossos).

In The Chronicles of Narnia, the Minotaur is a breed of mighty warrior, while in the Percy Jackson series it is a minor antagonist that exists outside of its labyrinth (and is killed by having its own broken horn impaled through its heart). It crops up in all manner of other realms too, from Disney’s Hercules, to Scooby Doo, to Doctor Who, to Jim Henson’s The Storyteller, to all manner of video and role-playing games like Assassin’s Creed and Dungeons & Dragons. There’s even a cameo from the Minotaur in the second Anchorman film. Elsewhere, the name and image is used to represent strength and power, like WWE’s professional wrestler “Mantaur” from the mid 1990s, to the robot called “Minotaur” from the TV series Battlebots.

The setting or other such details may vary, but the image of the Minotaur is consistent: a gigantic beast with intimidating features and strong fury. The character is rarely fleshed out to have any of its human side showing, and if it is, it tends to be a flippant self-referential remark (“I couldn’t choose my parents, you know” says the Minotaur from Disney’s Hercules TV series). There are exceptions (the Minotaur from Jim Henson’s The Storyteller is surprisingly one of the most human and affecting representations, which isn’t entirely surprising given the show’s young target audience), but first let’s look into Krug’s portrayal that bit more.

Instead of a one-dimensional focus on the bull side of the Minotaur, Krug channels the human half; this side has accepted their fate, their shamed existence, and that they have no control over their coming and going from the world. Krug’s Minotaur has questions he throws into the air: “Tell me, tell me / Were you really in a spell?,” he asks on “Minotaur Forgiving Pasiphae”, questioning her overwhelming lust for the white bull. At the other end of the song cycle he makes enquiries to the white bull’s creator, repeatedly uttering, “Why Poseidon?” over and over, his lamenting voice saying all that needs to be said.

The most heartbreaking questions, however, come on “Minotaur Forgiving Theseus”. As the rippling steel drums die down to reveal a shallow bed of marimba, Krug’s vocoder voice becomes small and teary. “But what did I ever do to you? / And what did I ever do to him? / And what have I ever done to anyone?,” he asks Ariadne and Theseus in a heartbreakingly childish voice as they plot to slay him. The Minotaur, for this moment, becomes a whimpering child lost and alone, like those he would devour in his labyrinth.

But Krug’s Minotaur still has a sense of humour. On the same track when the Minotaur comes to address his killer, Theseus, he does so with an almost jocular tone, knowing full well the fate that lies ahead. The drums that open “Minotaur Forgiving Theseus” arrive with pomp and a certain grandiosity, like the Minotaur has laid out the red carpet. “You’re just a hitman,” the Minotaur pipes up repeatedly, belittling Theseus as best he can, while also knowing full well what he’s here to do. There’s even a potential jibe with the following passage that comes immediately after the above questions:

“So come on in!

You can see what I’ve done with the place

You can walk on the bones of the innocent

And the weak

Theseus”

One chuckles at the Minotaur’s humour here, as he presents his bone-filled prison like he’s decorated it deliberately so. Not only that, the final two lines read two ways. While “And the weak” is likely just a follow on from the previous line describing the bones of sacrificed children, it’s easy to read the final two lines together, the Minotaur throwing Theseus an insult and calling him weak because he wants to antagonise him into killing him.

Indeed, the moment of death for the Minotaur is a pivotal one, and one where other more thoughtful representations of the Minotaur converge in some way. Krug makes no immediate reference to the Minotaur’s death, but it is very much on the cards: “And some will say you used your blade / And some will say you used your speed / Either way you’re going to win / Theseus.” The ambiguity in Krug’s lyrics no doubt comes down to differing accounts on how the Minotaur was slain, depending on what sources you reference.

In visual media (such as in Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief and the 2006 Tom Hardy-starring film Minotaur), the finishing blow seems to be the Minotaur getting impaled on his own broken horn, which offers up a self-destructive angle of thought. However, the sword seems to be the generally accepted weapon of death in most literature (though strangulation also comes up in one scholium on Pindar’s Fifth Nemean Ode). Who struck the blow though is also uncertain. Indeed, in Patric Dickinson’s book of poetry, Theseus and the Minotaur, Theseus cannot kill the beast, as he is so moved by his words. In this take, the Minotaur takes Theseus’ sword and kills himself. “Give me your sword / I put it to my heart and say / ‘Teach me a new word / And the meaning of it.’” The only word Theseus can muster is the final word of life: “death.”

This readiness to die also crops up in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The House of Asterion, a piece of literature that seems to have directly inspired Krug’s take. Consisting of a short inner monologue of the Minotaur, we get the perspective from the unnatural narrator that helps humanise the creature. Like on “Minotaur Forgiving Theseus”, Borges’ Minotaur awaits their fate. “‘Would you believe it, Ariadne?’ said Theseus ‘The Minotaur scarcely defended himself.’”, ends the story, alluding to a Minotaur ready for death.

Accepting fate comes up throughout Krug’s songs, and it no doubt feeds through to the forgiveness the Minotaur offers out. On “Minotaur Forgiving Minos” Krug’s Minotaur has come to peace with the fact he will never find a way out of his labyrinth. “I stopped looking for the way out years ago,” he sings, almost robotically. So beholden to this claim is he that he concedes further, “That sadistic inventor did a fantastic job.” On “Minotaur Forgiving the White Bull” he comes to a series of conclusions:

“So I guess you are my father

And I guess that she’s my mother

So I guess I am a prince

And I guess I am a bastard

So I guess I am an outcast

And I guess I am a monster

And I guess I am a god

Since a god was your maker”

Despite his high status as a member of royalty and as a descendant of a god, the Minotaur is still rejected. His monstrous appearance and bastardized creation is enough for him to be hidden away in shame.

The most intriguing and fascinating portrayal of acceptance comes on the standout track “Minotaur Forgiving Knossos”. “I have accepted it / I’m disconnected” and “I have accepted it / I am connected,” Krug sings repeatedly, succinctly summing up the fate of the Minotaur in a few words. The Minotaur is separate from everything and everyone (both literally by being trapped in his labyrinth and character-wise by being a supporting actor in everyone else’s story), but also inherently connected (the Minotaur sets into motion the deaths of King Minos, Theseus’ father Aegeus, and Daedalus’ son Icarus, for instance). The Minotaur is pivotal, but at the same time, rarely given due credit for being so.

The Minotaur lives in a state of conflict, much in the same way Frankenstein’s Monster does: viewed as something to be destroyed (if not locked away), but something that is yearning for nothing more than understanding and emotional connection. In Krug’s take, the conflict goes to his forgiveness too. In all the songs the Minotaur (as the titles suggest) forgives – but he does so sometimes with hesitance. “And I guess that I forgive you,” he concludes on “Minotaur Forgiving the White Bull”, whereas on “Minotaur Forgiving Minos”, his mind is even more conflicted. “And I hate that I forgive you / But I do / I just don’t know why.” Whether this is a creature beaten down to forgive by the horrific circumstances in which they have to live, or just an inherently human being overcome with inexplicable sympathy remains a mystery for the listener.

It’s of little surprise then that Minotaur despairs as he does, especially since the conclusion of his existence is a deeply sad one: he exists only as a means for which Theseus has to prove his strength. As Alison Traweek puts it in her essay on Viktor Pelevin’s modern take on the tale of the Minotaur, The Helmet of Horror: “Moreover, he exists almost exclusively to provide an initiatory test for the hero: he is precisely the force of savagery that allows the hero to perform his heroism.” Pelevin’s complex and intriguing take goes one further, one of the main characters in the book realising that “Asterius’ [aka the Minotaur] greatest secret is that he’s entirely unnecessary.” Krug’s take on the tale and the Minotaur would point towards this being knowledge in the Minotaur’s head, even though he never explicitly expresses it.

V.

In the depths of my depression in late 2018/early 2019, I stared death in the eyes most days. It was an appealing option to me at that moment; a release from all the pain I had caused and was going through. I both wished my own Theseus would come and put me to sleep, and also that I had the gumption to do as Patric Dickinson’s Minotaur did. But Krug’s music was like a rubber ring, keeping me floating on the surface: at the thought of letting go and submerging myself, I would slip into these tracks once again so as to abate the suicidal thoughts.

Like the Minotaur, I felt like I was retracing steps over and over, playing thoughts and memories over and over in my head to find some sort of meaning (as well as circling around the same suicidal ideations). The Minotaur spends years in his labyrinth, driven mad by the endless maze of corridors – something which is captured in both the words and the music. Krug and Bigelow traverse up the scales on their instruments and then topple back down them again, starting back where they began (the final third of “Minotaur Forgiving Pasiphae”, for instance).

“Minotaur Forgiving Daedalus” is probably the most obvious example, the chord pattern and lyrics circling around and around, over and over with echoing voices, always coming back to the same conclusion: “You built a labyrinth.” This inescapable chamber (along with the representative music and lyrics) is a symbol of the madness that befalls the Minotaur. Lost forever, going down hallways again and again, and ending up at the same place. To paraphrase Michael Gambon in Jim Henson’s The Storyteller: the Minotaur is the master of his labyrinth domain, for whatever use that is.

His wails for understanding and remorse are affecting though, from the moment he seems to be pleading to the listener directly (the aforementioned heartbreaking passage from “Minotaur Forgives Theseus”), to the repeated utterances of “why?” over crystalline steel drum notes on “Minotaur Forgives Poseidon”. The Minotaur’s fate is set from the moment the white bull comes into existence; he is no part of any epic story cycle, and once he is gone, he is just a reference point. While he may look like a savage animal, he is still half-human, and he is still capable of regret, shame, and – so central to Krug’s take – forgiveness. Even such a troubled being could forgive his captors, creators, and destroyers, and if the Minotaur could do so, then, I concluded from my pit of personal loneliness, maybe the people I hurt could too.

For these dark months in my life these songs were my hope. And that’s why Krug’s music was so enveloping and brilliant to me. It not only helped me slowly find the way out of my own psychological labyrinth of depression and anguish, it also gave me hope for the future. Forgiveness is possible, and from the beautiful tones and haggard vocoder-affected vocals, this album teased this message to me over and over through both direct words and inventive storytelling. I know Krug noted in the press release for the album that “these songs are not meant to be taken seriously,” but I saw myself in the Minotaur. I did what so many of us do with music: forge an emotional bond from potential meaning and find ourselves between the lines. Through all this, the Minotaur stared back at me. “I forgive you,” he said, and with those words I could start healing.