Matthew Herbert loves sounds. In a brief interview with Dummy Magazine, he lists his ten favourite noises that his newly renovated and converted house makes, ranging from the melodical qualities of his toilet bowl, to the scratching of a tree on the roof, to the thud his young son makes when he falls out of bed. It’s a wonderful little insight into the way Herbert’s mind works, hearing music in everything that would otherwise be deemed every day and forgetful by any other person. Of course, the article isn’t entirely surprising to anyone familiar with Herbert’s work, which has ranged from his grand One trilogy (which included an album consisting entirely of noise made during a pig’s life) to his recently reissued 2001 album Bodily Functions, which recreated the sounds of handbags and bones into a danceable masterpiece. Somehow though, his latest album – The End of Silence – sounds (once again) completely innovative and manages to sit separate from his previous work.

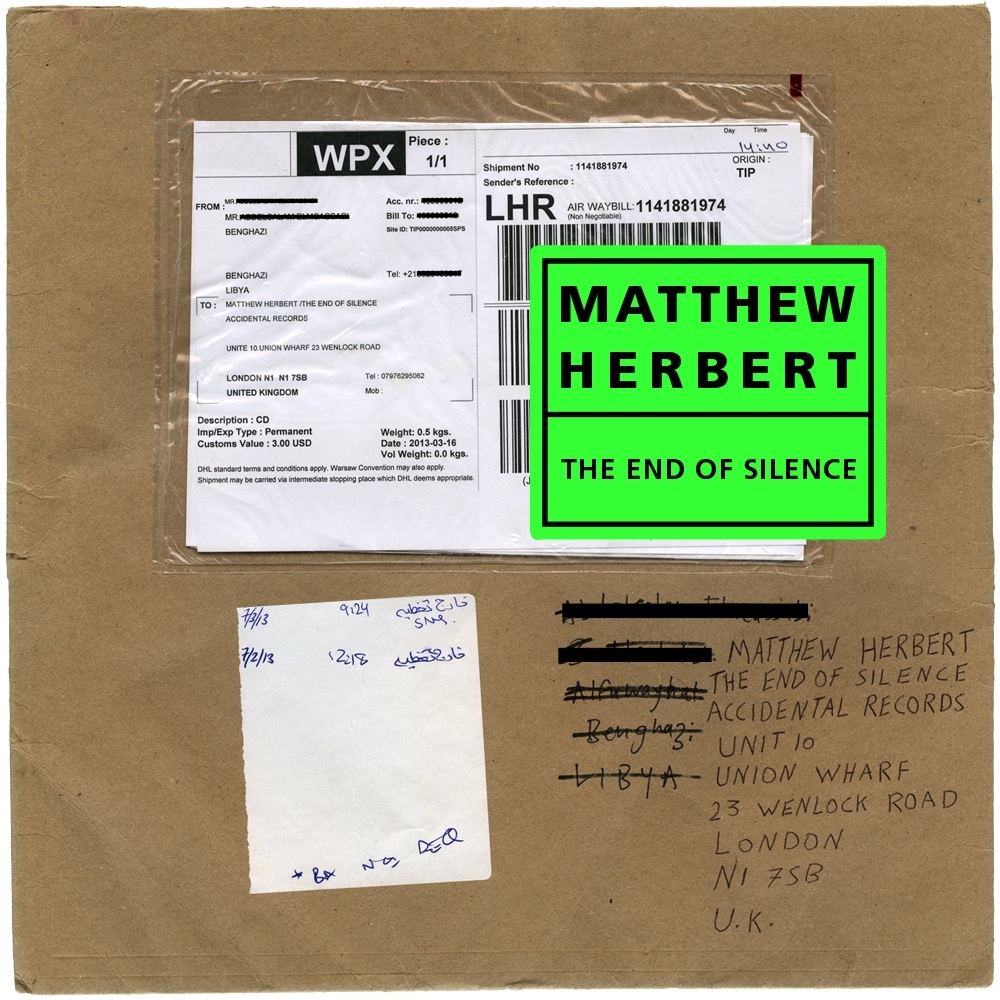

The End of Silence consists of one five-second sound sample captured by war photographer Sebastain Meyer as a Gadaffi war plane flies over and drops a bomb somewhere in Libya in 2011. From this dramatic and distressing clip, Herbert and a few bandmates (Yann Seznec, Tom Skinner and Sam Beste) create the three-part, fifty-minute album, warping the original sound into atmospheres, beats, and rhythmic soundscapes. The most expansive example of this is “Part 1,” which introduces the clip right at the beginning and, from there, burbles and fidgets about anxiously, occasionally lulling into a low chiming introspection where what sounds like a distant huge bell is hit every so often. Comparatively, “Part 2” is much more active (and also the shortest of the three parts at ten minutes), transforming into something resembling one of Herbert’s traditional dance tracks, although you’d be in odd spirits if you really wanted to move about to this.

The problem with The End of Silence is that it’s hard to describe accurately and consequently to talk about musically. It’s the concept which takes the focus here, as the album is essentially Herbert speaking about how he feels about multiple issues, such as war, technology, interpretation, separation, and humanity. The five-second Meyer clip is a lighting shock of reality which most of us are entirely absent from, yet we can still experience in realistic formats. While recording the album over three days in a barn in Wales last year, Herbert also set up a series of what he calls “witness mics” which recorded the sounds around the barn in parallel to the takes being performing inside. It’s an effective, if not evocative way of representing how we consume horrific tragedies like war: we can listen, watch, and experience it on HD TVs with surround sound, but around us is our everyday peaceful existence. We’re separated from it all while we can simultaneously choose to be part of it.

The important lesson Herbert seems to be subtly trying to represent is that life goes on in this peaceful way, and after you’ve watched the news piece about a tragedy in some distant country, the sound of your child falling out of bed will bring you back to your own life. During the album’s runtime, you’ll hear chattering noises that resemble machine gun fire, carnivorous bellowing from what sound like huge metal robots, or angry dissonance like an overload of TV static – but every so world outside the barn will seep into the picture. Birds chattering, a dog barking, or perhaps just the faintest gust of wind; war, or the sounds of war, are relative to life as a whole. There is anger and explosions somewhere, but at the same time there is peace and tranquillity.

Limiting himself to just one sound clip, it would be assumed that Herbert limits his palette, but in the case of The End of Silence, that doesn’t really seem to be the case. The amount of differing noise that’s created over the album proves that Herbert (and his band; though it’s impossible to tell who is doing what exactly) is master of his trade, and while the album might not offer as much sonic variety as other records, he proves here that’s he not just in it for the simple joyful kicks of seeing what music he can make out of a crisp packet or kitchen utensils. The End of Silence is a serious statement that can bring the harshness of war to your ears and occasionally make you rethink how casually you consume the news. It’s by no means an easy album to wander through – especially since the five second clip spontaneously appears across the album, shocking you back into (or out of) deep listening; “Part 3” is most visceral in using it, morphing it into a deep, crunching, thunderous sound – but I doubt it was ever Herbert’s intention to make this “easy listening” in any conventional sense of the term. It’s a statement if anything, spoken without a single word; apt considering any veteran will likely tell you there are no words for the horrors of war.