Content Warning: Contains mention of themes of suicide and addiction

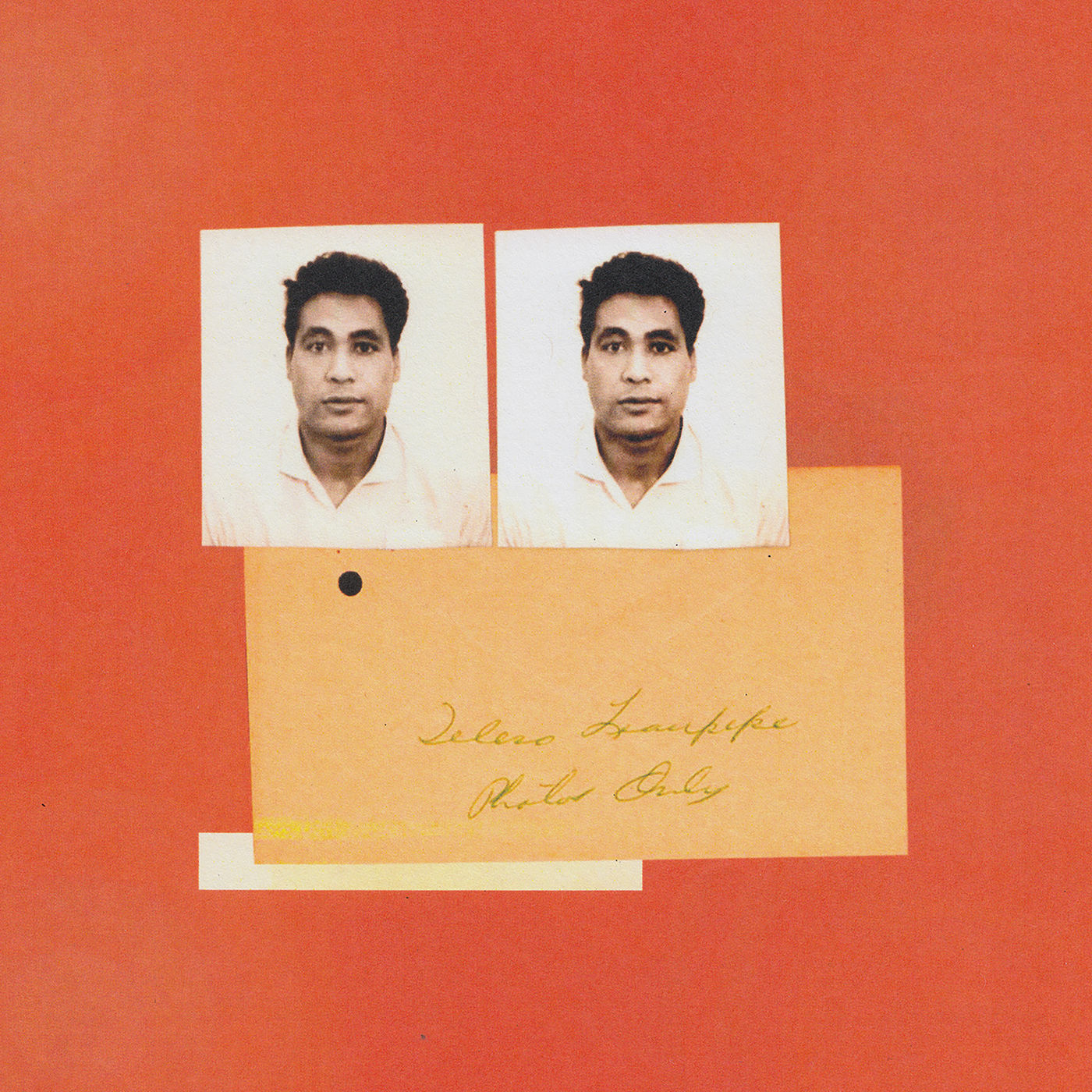

Gang of Youths frontman David Le’aupepe has spent the last decade excavating past and present anguish in the glaring light of the public eye. Both 2015’s The Positions and 2017’s Go Farther In Lightness were informed by a series of truly traumatic events; a partner’s stage 4 cancer diagnosis, marital breakdown, a suicide attempt, addiction and a stint in rehab. Yet another tragedy defines angel in realtime., the third album of indie-rockers Gang of Youths – this time the death of Le’aupepe’s father. Cruelly, it has often felt as though each time Le’aupepe’s career was taking off, his life was falling apart.

Despite having stared down a lifetime’s worth of tragedy over the last decade, Le’aupepe remains optimistic. In interviews, he is warm and affable – while also strikingly blunt when recounting his troubles. In live performances, he boldly tells of intimate truths that most would be afraid to admit to themselves, let alone to crowds of thousands of people. He claims the stage as his own from the second he steps on it; dancing insouciantly across it and interspersing songs with personal anecdotes that range from charmingly mundane to strikingly intimate. He makes direct eye contact with front-row audience members, while making sure his words pack an equally powerful punch for those at the very back of the room. Both the band’s subdued ballads and anthemic rock numbers – that recall The War On Drugs and Sam Fender – leave audiences mesmerized. Unquestionably, Le’aupepe is one of the best live performers to emerge from Australia in recent memory.

Outwardly, Gang of Youths’ third album is one about grief – specifically the grief stemming from the death of Le’aupepe’s father. But more than that, it’s a moving and deeply personal exploration of the innate flaws of the human condition; of failing the ones you love despite your best intentions, and of falling apart and beginning the slow and painful process of piecing yourself back together again afterwards.

angel in realtime. paints a sympathetic portrait of Le’aupepe’s late father, but never a whitewashed one. Across 13 tracks, he tells of a man who lied to his loved ones about when and where he was born and went on to up and leave two of his children for the entirety of their childhood. Never damning or unforgiving, however, we’re reminded that often the most painful actions from our loved ones are underpinned by good intentions. Maybe he lied to “give his kids a better chance” Le’aupepe suggests on “Brothers”.

Indeed, much of the anger on this album is reserved solely for Le’aupepe himself. On the shimmering, stadium rock number “In The Wake of Your Leave”, the singer begins as the “loser at your funeral”, but by the song’s end he’s irredeemable (“Nothing would absolve me”). “How do I face the world / Or raise a fucking kid?” he asks in “You In Everything”; facing down existential doubt with characteristic matter-of-factness.

On the best song here, “Forbearance”, Le’aupepe paints a particularly ruthless self-portrait – recounting sitting on the pavement and watching police cars arrive after his drunken suicide attempt. “I was a big piece of shit” he declares before moving on to reflect on his father’s final days and weeks. In the song’s second half, propulsive drum machines and strings fade out and Le’aupepe is left alone at the microphone, where he delivers the album’s most devastating revelation: “And if the whole thing was fair / It would be me that was fighting for air”.

But, just as Le’aupepe ultimately manages to find a sympathetic light to portray his loved ones in, eventually he finds similar mercy for himself. “Spirit Boy” begins on a particularly unnerving note – “God died today / He left me in the cold” – but across the song’s six-and-a-half-minutes he finds grace in the world around him; in the beauty of London, in the love of family and friends, in a funny show on ITV – and, if all else fails, in the mere passage of time. Following “Spirit Boy”‘s midway interlude of indigenous Samoan music (over half the album’s songs feature such samples – an admirable attempt to stop this musical tradition being lost to the oppressive forces of colonialism), Le’aupepe stumbles upon his most optimistic realisation yet: “And I still believe / Magnificent isn’t hard to find”. The brutal exploration of pain up to this point makes this revelation all the more convincing and affecting when it finally arrives. It stands as a testament to angel in realtime.‘s core message – that life is rarely easy, and often painful, but ultimately always worthwhile.