For 17 years, Natasha Khan has worked on a vast, personal esoteric catalogue of images and characters. From the sensual imaginary soulmate Daniel to the self-immolating Laura and mourning bride, she conjures these entities like spirits, referencing occurrences that might be hidden in prior or coming albums, without ever making connections too over. Often citing David Bowie as an inspiration, her works under the Bat for Lashes monicker have explored gothic horror, religious semantics and hypnotic romanticism, dabbled in poetry and pop. On her best work, the startlingly beautiful and inherently carnal The Haunted Man, Khan broke through these characters, catching a rare glimpse of eternal struggle that could frame a volatile relationship as much as her own perceived writer’s block: “From inside his mouth, I lick the blood.”

Since then, we’ve only had two more and diametrically opposing works – the imaginary soundtrack and subversive mourning story The Bride and the strange synthpop vampire epos Lost Girls. Both albums were riddled with purpose and symbolism, in their own right incredibly rewarding pop albums that would deserve to make the numbers and scores of any Lana del Rey or Taylor Swift record.

Yet Khan’s appeal has always been more interested in cryptograms and perversion than that of her more achieved musical siblings, somehow making her the Cinderella of modern pop. To say that The Dream of Delphi could change that seems bizarre – the album has been accompanied by mostly polite praise from critics and audiences (so far), written about in the generally quizzical tone of bemoaning a lack of “songs” and framed in the embrace of Kate Bush’s pastoral heritage.

And yet here I am – a little late due to extensive travels and lack of time – some dozen spins in, and I can’t help but find myself in utter awe of this immaculate work, which combines thrilling minimalist compositions with crushingly emotional vocal deliveries. A letter to Khan’s infant daughter – as well as a solemn reflection on the folded relationship to the child’s father – it resides in the company of records that are just as sternly personal and have alienated audiences just as much.

The two records which come to mind here are TFCF by Liars and David Bowie’s Buddha of Suburbia, both regarded as the black sheep of their individual discographies (with Buddha… not even released in most markets). Both albums reflect on personal landscapes – inside and outside – of rebirth and separation. They also, similar to Delphi, explore ambient, piano and keyboard compositions and dance music.

Take, for example, how Bat For Lashes’ single “Home” toys with house music, similar to what Bloc Party attempted on “One More Chance” in the past. The irony, that the journey home is contrasted by a repeating piano line and electronic beat that interrogates the movement of dancing (implying that there’s a stark liminal in-between dancefloor and motherhood) suggests that the moment of travel and constant change might ultimately be more important than the arrival – that home is within.

Similarly, the instrumental “Breaking Up” uses the aesthetics of a Ryuichi Sakamoto composition – xylophones and asian instrumentation contrasted by a lush 80s saxophone melody – to express diverging mindsets. AIR similarly united those western and eastern elements too, on their record Pocket Symphony, to debate their own implied ageing.

Philosophically, Khan picks up these ideas of expression, of a symphony that is ultimately created and performed within one’s own head, and bedroom. Delphi – both her daughter and a higher ideal (it’s not a reach to make a link to the oracle of Delphi) – is characterised as a force of joy that extends beyond Khan’s head, and time itself. When the electronic waltz of “Delphi Dancing” ends after roughly one and a half minutes, the melody is picked up by a piano, indulging in a Mozart-like tone, before it slowly fades into the echo and turns into the Brian Eno-like “Her First Morning” – a contrast to the Hiroshi Yoshimura flavoured “Christmas Day”, which uses spoken word poetry to express the simple mindfulness of motherhood.

Here it is important to reveal an important side note: as a man, it is certainly unlikely that I will ever be a mother, or know what this process of physical experience and emotional attachment feels like. Same is likely true for many other reviewers who approach this album. When Khan uses “Letter to my Daughter” as a means of genealogical cartography, speaking as much of feminine ghosts as of artistic DNA (“Remember you came from a spiral unfolding / A tender star while magnolia are slowly unfurling”), the process of expression that she uses remains rooted in abstraction. It’s not a direct, prosaic statuesque build that defines motherhood to the listener, but a predominantly minimalist understanding of how each compositional element attaches itself to this experience that, to Khan, is ultimately spiritual.

A drone inspired track like “The Midwives have left” puts this into stark focus, as it is ultimately much more than “just” a humming instrumental of piano, voice and harmonica – it shows the artist longing for solitude and sketching her without any of the spectral companions of her past. The ghosts and monsters she serenaded in prior albums aren’t embodied, but they are felt more so in their absence, in their lack of presence.

Thus, The Dream of Delphi is both hidden and concrete. Khan here is more starkly naked than ever before, but at the same time she’s found a veil that allows us to see only shades. Speaking of Bowie again, it might also tie to his concept of Low, an album that used codified poetry to express depression and separation to mark “a new career in a new town”. Where Bowie chose a “Weeping Wall”, Khan explores “Waking Up” – both songs explore Steve Reich’s nervous xylophone playing, but where Bowie’s was reflective of cold war anxiety, Khan’s poses an unsaid question, finally ending in a moment of abandonment, of remove from sleep.

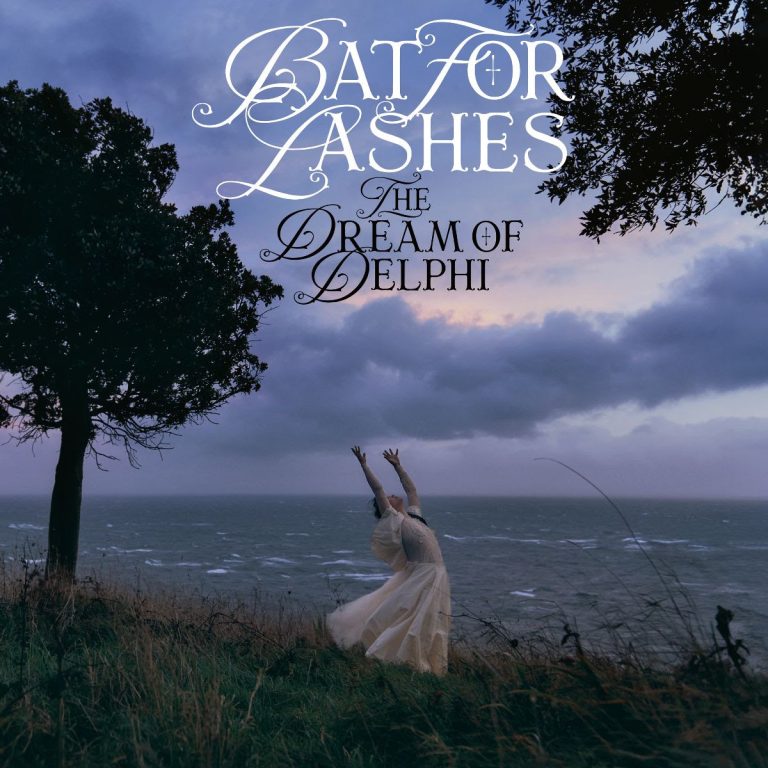

Maybe this is the one criticism that could be applicable: that Khan’s work here is too reliant on the hypnagogic and rural, that she rarely ventures outside, into the tempest, the fields and sea that mark the album’s cover. In the tonally very similar Field of Reeds, These New Puritans did just that, creating a masterpiece that lives on between grim techno netherworld and Lynchian jazz club. Khan at times alludes to these movements (most prominently in “Home”, but also with the Björkisms of the title track), but her focus on interior realms might connect a little too closely with lockdown experiences for a moment in time when collectively, the journey outward (into the world, into the clubs, into politics) is all the more important. Still, it’s an unfair criticism to reduce a mother’s exploration of how quiet sounds can frame the shades of inner worlds in bright new colours to an absence of pop. And in a catalogue as rich with esoteric bangers as Bat for Lashes’, a work this defined and heartfelt still is a striking gem. A hushed secret, it has more to offer than just that.