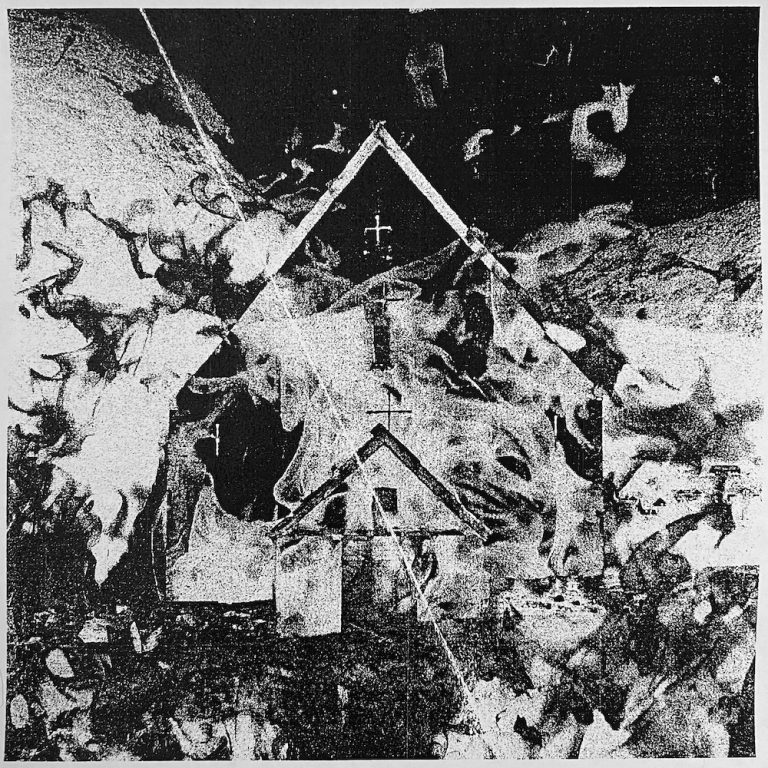

With 2020’s God Has Nothing to Do with This Leave Him Out of It and 2021’s I Lie Here Buried with My Rings and My Dresses, Ashanti Mutinta, aka Backxwash, invokes what psychiatrist and researcher Vivian M. Rakoff called generational trauma and instapoet Hanna Abideen dubs “the scars of fate,” navigating personal and transpersonal PTSD. Mutinta displays a unique craft; however, it’s her ability to channel instinctive impulses and archetypal states – tensions inherent to the evolutionary continuum, to the very act of creation as depicted in origin myths – that renders her a talented alchemist and seminal provocateur.

With her new album, His Happiness Shall Come First Even Though We Are Suffering, Mutinta completes her epic trilogy, continuing to name and explore shame, doubt, self-loathing, violence, and addiction, while musing on the intergenerational nature of these “possessions.” On “Vibanda”, she mixes hauntological textures – glitchy beats, eerie piano accents courtesy of Morgan-Paige, and dashes of acidic guitar by Michael Go – with horrorcore vocal tones, snarling: “What is stress? / what is peace? / what is death? / what is love?”

“Nyama” opens with Pupil Slicer’s spellbinding growls, recalling Ada Rook’s blistering contribution to I Lie Here Buried’s title song. While Mutinta’s lyrics are obliquely engaging, it’s her visceral delivery, again, that translates more immediately. Her sense of urgency, indeed panic, exceeds everyday issues, evoking the biblical fall and ontological collapse into egoic nihilism. Milton’s Satan, disguised as a poetic rake, whispers in her ear. The exiled angels ruffle their wings in the periphery.

Lingua Ignota’s Caligula and Sinner Get Ready, along with King Woman’s Celestial Blues, are sister projects, though Kristin Hayter often embraces a frantic prayerfulness in the face of disconnection from source, while Kristina Esfandiari frequently adopts a fem-fueled defiance. Mutinta, however, uses rage not to deflect her dejection but rather to bare herself more fully to the legacy of humankind’s descent. She opens herself to the mythologized suffering of the Christ figure, even as she rejects Christian piety, navigating a sense of adrenalized despair that can’t be assuaged with ecclesiastic rituals, promises of salvation, cultural manifestos, Lorazepam, Paroxetine, heroin, or copious amounts of alcohol. This is the irremediable paranoia, the sense of conspiratorial guardedness, that Philip K. Dick wielded in much of his work: beholding the truth about reality is like plunging into a bad trip that never ends. Rather than setting you free, the truth can drive you insane.

On “Muzungu”, which opens and closes with racially-charged clips from speeches by Malcolm X, Mutinta blends theological references, equalitarian declarations, and a volatile meditation on death; “Let’s blame the Eves then / snakes for treason / the dead won’t listen / if Lord forgives them.” Gospel, blues, and metal tones are synthesized, bringing to mind Zeal & Ardor’s eclectic debut, Devil Is Fine (an eclecticism unfortunately abandoned with their recent eponymous release). On “Zigolo”, Censored Dialogue and Sadistik complement Mutinta’s sinister vision, the latter offering the memorable couplet, “Homie said God is my enemy / to show me he offered me ketamine.” The track brims with bassy drones and churchy chords, fusing B-horror sonics and blackgaze a la an Elevation band experimenting with crunch pedals while spiraling on ayahuasca.

Ghais Guevara offers a seductive meld of anecdotalism and swagger on “Juju”. The confessional tenor of his segment (“What if you slip / what if you fall?”) prompts a vulnerable response from Mutinta (“Between you and I / I survived my own suicide”). On “Kumoto”, Death Grips and Ho99o9-inspired noise-sprawls wrap around Mutinta’s voice as she pivots from hyper-vigilant and semi-staccato assertions to a vortical cadence reminiscent of Eminem.

The project closes with “Mukazi,” Mutinta rapping heartfeltly about suffering and the wisdom that can emerge from it. Her lilting delivery and lyrical perspective (nostalgia meets bildungsroman) indicate a substantial affinity with Kendrick Lamar. As the song nears completion, Mutinta’s voice is complemented by pop-adherent back-up vocals. The track drifts into an R&B-leaning riff on 70s Motown.

With His Happiness Shall Come First Even Though We Are Suffering, Mutinta completes her heroic triptych. Processing her own fury and the fury stashed in the world’s memory (what Jung might call a collective shadow), she asks important questions: What is consciousness? Is there a living God? What is sin, theologically and practically? James Baldwin opined, “An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell, because nobody else can tell, what it is like to be alive.” Mutinta accomplishes this and more, leaving us stunned, devastated, ecstatic.