Canada’s long-running Bell Orchestre spent a good deal of their early existence living in the shadow of their Quebecois brethren Arcade Fire, and it’s easy to see why. The two bands share a couple of members, and, especially in the latter’s beginning years, create particularly symphonic indie rock music. One key difference of course is that, while Arcade Fire’s songs relied as much upon their skyward grooves and sparkling swells as it did Win Butler’s and Régine Chassagne’s vocals and lyrics, Bell Orchestre have mostly created instrumental music. The group is a self-described “mini orchestra,” and it’s evident from their first release, 2005’s Recording a Tape the Color of Light, that the music they made together was quite different from Arcade Fire’s. Despite this, the more pop-oriented group definitely took most of the limelight, not aided by the fact that Bell Orchestre haven’t put out a new album since 2009.

That all changes now, though, with their long-awaited third album, House Music. Their first release for the Erased Tapes label, House Music finds the group in top form. Some of the delay between releases is due to the fact that many of the members are also in other bands. Sarah Neufeld (violin and voice) and Richard Reed Parry (bass and vocals) have been working with Arcade Fire for years, which certainly keeps everyone involved quite busy, while Pietro Amato (French horn, keys, and electronics) works with them in addition to The Luyas, along with Stefan Schenider (drums). Kaveh Nabatian (trumpet, gongoma, keys, and vocals) is also a member of indie rock outfit Little Scream, and Michael Feuerstack (pedal steel, keys, and vocals) has a couple solo projects.

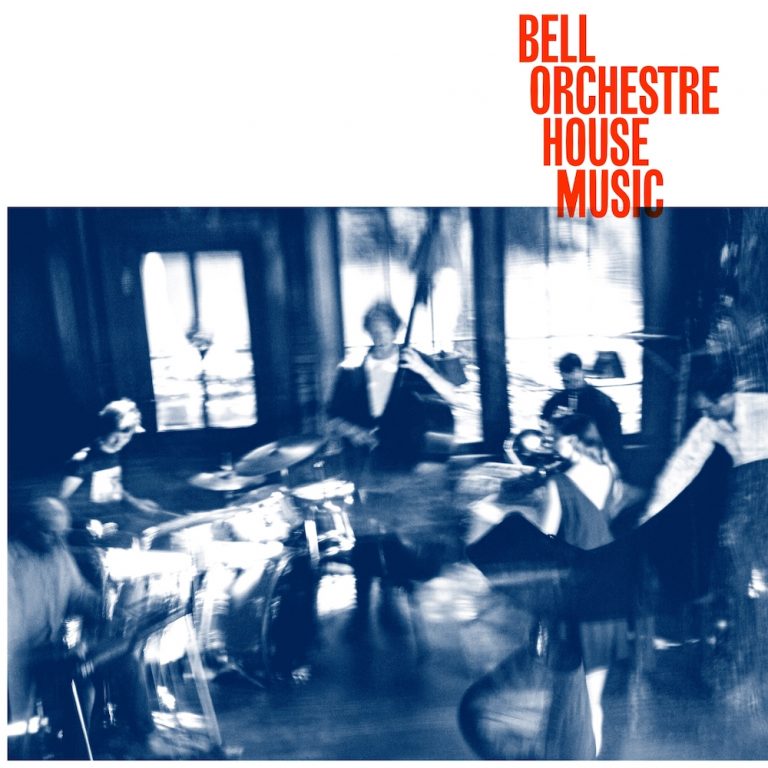

It’s a lot. And yet somehow, the whole group, along with wizard engineer Hans Bernhard, finally found time to get together and make some more music as Bell Orchestre. The story goes that they convened at Neufeld’s remote house in northern Vermont, with each band member occupying a separate room of the house. They had screens and sound set up to watch and interact with each other, and mics recording every sound they made. Then, together, from all across the house, they played. They reportedly played for long hours, across two weeks, improvising as a group and seeing where the muses took them. House Music is a product of those sessions, itself sculpted out of a specific 90-minute session, whittled down to an easily-digestible 45-minute release.

Aside from a few unnoticeable overdubs or retakes, the 10 songs here represent a coherent, ever-changing jam, captured in real time. Techno wizardry aside, the album is remarkably consistent and fluid, each song bleeding sonically and tonally into the next with grace. After a brief opening wash, we get the first proper song, “II. House”, and we’re off. A yearning violin glides alongside some plucked strings and brushed cymbals; a soft pedal steel appears, as if materializing out of nowhere and yet it sounds like it’s always been there. It’s a gentle opening, conjuring a yawning landscape and blissful skies, but it’s also a perfect entrance to the album. It shows you snippets of the tools the band has at their disposal, and then the rest of the album shows you what they’re really capable of doing with these tools, inverting and subverting expectations at almost every turn.

As “II. House” picks up steam, rumbling percussion and rubbery bass entering the frame, it’s clear that the group has lost none of its original alchemy in these intervening years. “III. Dark Steel” has a dark, stormy horn base, almost like something off a Colin Stetson record, while Neufeld’s violin skates queasily overhead. It’s like the aural equivalent of a chase scene through dusty alleys. “IV. What You’re Thinking” includes some vocals, something that ha been a rare addition to a Bell Orchestre’s songs previously but come in here and there across House Music. They’re not exactly lyrical: it’s more akin to something off Animal Collective’s Sung Tongs, yipping and calling out, the only response being the intensifying, dizzying array of sounds around them. Vocals are also audible later in “VIII: Making Time”, but this time they sound as if they’re being breathed through the horn, again recalling Stetson’s bellowing, impressionistic sax pieces.

There are moments across this record that are just stunning in their fluidity, and in their beauty. “V: Movement” has a horn progression that sounds almost like a long-lost jazz standard, garbled and warped by time, along with some gentle “ahh”s from the group. “VII: Colour Fields” has a subtly growing horn and string section, blooming slowly alongside intergalactic synth licks and a percussive pace that doesn’t quit. The drumming across the record is astounding, both in Schneider’s ability to keep up with vigor and grace, but also in the clever ways in which it helps the ideas and phrases congeal together, providing a solid rhythmic framework for all the winding sounds.

House Music rewards as a passive listen, to a degree, but to really appreciate and notice its depths, it does require a good deal of patience – perhaps more than some would be willing to give. There are some slight missteps, like the shorter, kind of inconsequential “VI: All The Time”, which is mostly full of distorted synth notes and percussion, or the pretty but slightly lackluster finishing track, “X: Closing”, which has the slight misfortune of coming after the gorgeous and similarly spacey and languid “IX: Nature That’s It That’s All”.

But, more often than not, this album is deeply enthralling, providing interesting textures, head-swaying grooves, tight rhythms, and an awesome display of synchronicity amongst the bandmates at almost any turn. It’s a maze that’s a joy to get lost in. With production this spacious and pristine, and players this skilled and in sync with each other, it’s mostly just a shame it took them so long to release a new album. Regardless, House Music stands as their finest document so far, spelling only excitement for what’s to come.