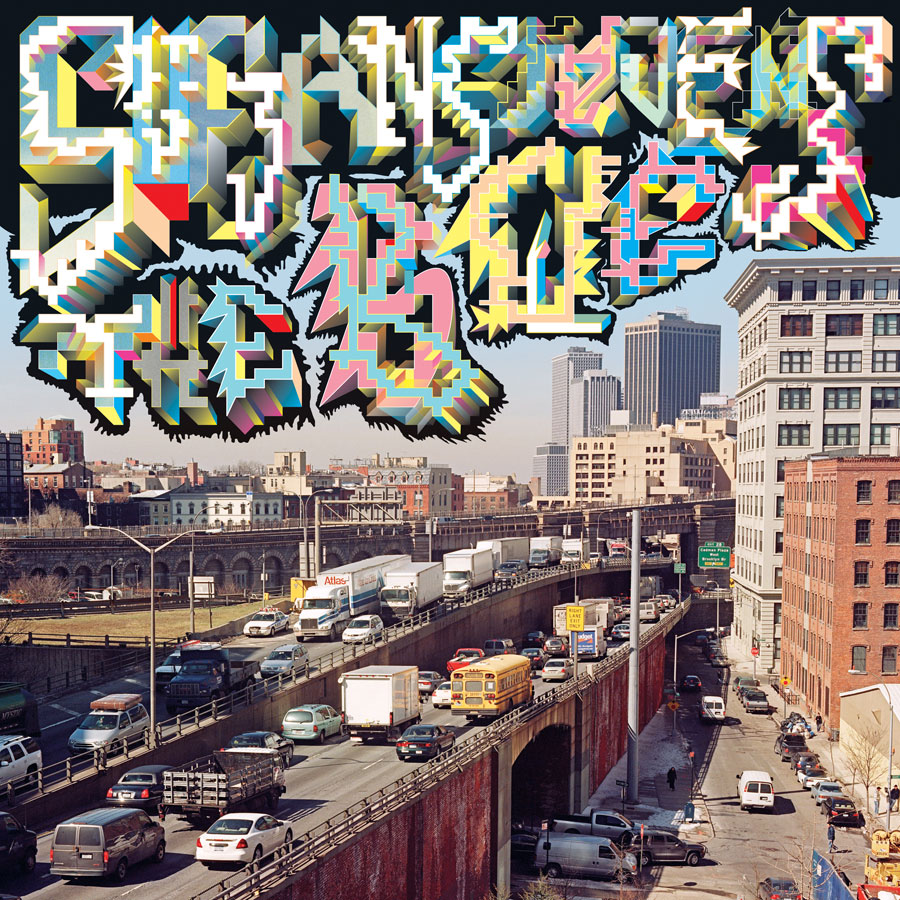

For anyone else, putting forth an idea for a project like The BQE, questions would probably be asked as much as eyebrows would be raised. But for someone as prolific and as seemingly random as Sufjan Stevens, nothing seems amiss. The prospect of an orchestral piece with accompanying films, comics and 3-D Viewmaster reels inspired by The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and The Hula-Hoop seems almost natural for a guy who’s released an electronic album all about the animals of the Chinese zodiac and more Christmas music than most musicians would in two lifetimes.

And with the consistency Stevens has, expectations are undoubtedly high, especially when so many are still waiting for a third album about an American state. But the 50 States project seems like a curse now for him, with anything not thematically built upon one not considered a cohesive and proper album. And I suppose The BQE isn’t an album in a typical and conventional manner (then again, when has he been one to go for convention?). As said, it’s merely a soundtrack that’s part of a huge and brilliant idea that anyone else would likely have problems conjuring up. Perhaps the best way to fully experience this would be to have the accompanying DVD or attend one of the sold out performances two years ago. The music is fine, if not gorgeous and sublime the majority of the time, but there seems to be a fundamental emptiness when listening to it as you go to create your own visualisation in your mind of congested highways and peoples using hula-hoops.

The whole thing begins rather fittingly, despite being somewhat abstract. Heavy drones with washes of light fall over and into each other as faint melodies emerge – much like the blank white noise of gridlocked traffic, stuck in your own car, as stereos and background noise seep into your subconscious. But in a shot the noise disappears and we are welcomed with grand horns and flutters of woodwind – it’s the sound of a (somewhat) recent Sufjan if there ever was an identifiable one created from Illinois, but more stately than ever. And this grandiose is present throughout the majority of the runtime here – everything sounds at its best, polished to reflect light and dazzle. But it’s a good sheen that’s expected – with a 40 piece orchestra behind you there’s no room or need for any sort of spontaneity, the music is powerful and well crafted enough to do that on its own.

That said, the biggest surprise here has to be on the suitably titled “Movement IV: Traffic Shock” when a barrage of chirpy electronic comes into play, completely throwing aside any preconceptions you might have had about the work. Within its glistening walls it seeps familiars flutters, infusing the two worlds. It’s not obvious but it’s an interesting step taken. The other moment when things take a different turn, as well as a personal highlight, is “Interlude I: Dream Sequence In Subi Circumnavigation” where the music, already skating on thin and fragile strings and voices, takes one tiny step and suddenly finds itself drowning in even colder and disconcerting noise. But out of this once again emerges a sort of sensibility, like a miniature triumph rising from the darkness. That sounds corny I know but it’s hard not to revert to such pictures of clichéd images when you try to imagine how a highway could justify sounding so sinister. But perhaps it is as the title suggests – a dream where even roadways can become overwhelmingly ominous.

As a whole, apart from initial criticisms, this really is a fabulous piece of work. There are plenty of crescendos and motifs to keep the listener engaged whether it be the steady paced pizzicato build of “Movement III: Linear Tableau With Intersecting Surprise”, the warming strings that lie behind the staccato trumpet of “Movement II: Sleeping Invader” or the fanatic bobbing of the horns at the finale of “Movement V: Self-Organizing Emergent Patterns”.

However one constant throughout the album is the beautiful piano – it’s clear why bands like The National include Stevens in their creative process. The way it builds with the orchestra around it on “Movement I: In The Countenance Of Kings”, drawing in the other instruments against any sort of will they might have is majestic when reading about it but another experience when you come to hear it. The final piece “Postlude: Critical Mass” brings the whole thing to gentle, almost silencing end – a welcome juxtaposition to the huge fanfare that preceded it. It shows that, even with an orchestra and a choir and big idea around him, Stevens can still emote with the most sparing actions. And essentially, that’s the mark of a prolific artist.