What exactly is progressive about progressive rock? If by “progressive rock” you mean the grandiose classical canon worship of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, not much. Can you really call yourselves “progressive” when you’re stumping for composers from a hundred years ago? On the other hand, in the Canterbury scene and the Rock in Opposition movement, groups like Soft Machine and Henry Cow applied a jazz-influenced, improvisatory approach to composition. The music was heady, transgressive, and certainly innovative, but often thematically impenetrable. Even the most overtly political of Henry Cow’s songs, “Nine Funerals of the Citizen King”, couched its observations in literary allusion. When considered alongside the contemporaneous ascension of the more populist punk rock, heavy metal, and new wave genres, it’s not hard to see how prog-rock quickly wore out its welcome.

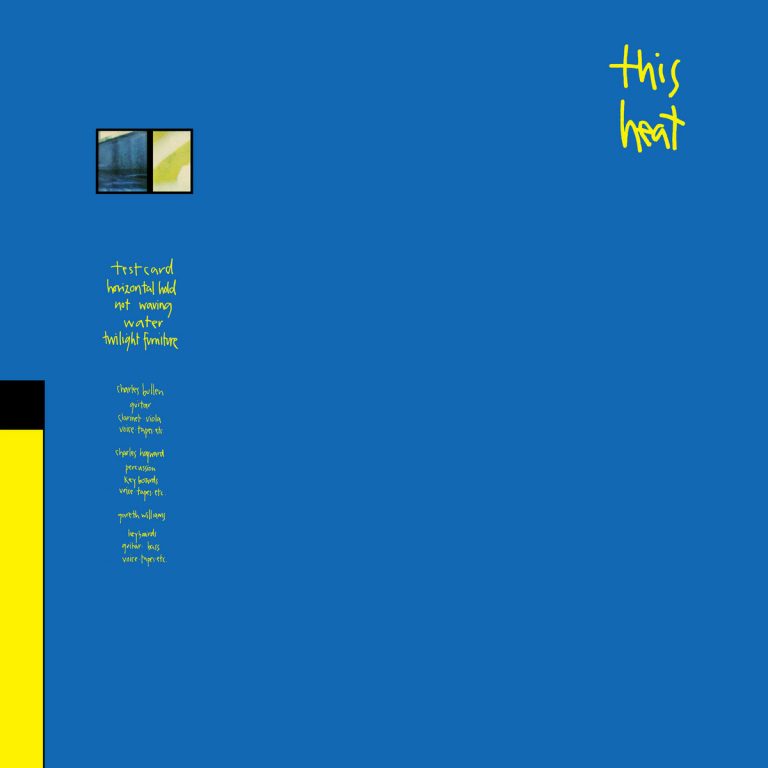

Perhaps the pathological abstractness wore thin on Canterbury scene veterans Charles Hayward and Charles Bullen. As their official Facebook bio puts it, “This Heat was formed from the collective desire of its individual members not to be in other people’s groups.” Recruiting self-proclaimed “non-musician” Gareth Williams, the band spent three years in Brixton studio Cold Storage combining tape loop experiments with a cut-and-paste approach to song structure, while casting an unflinching eye upon a world on the brink of apocalypse. At once avant-garde like prog, vital like punk, visceral like metal, and futuristic like new wave, This Heat has revealed itself in the ensuing four decades to be one of the most influential albums of all time, containing the seeds for the noise rock, post-punk, post-rock and post-hardcore that would follow.

The influence on future generations is apparent from the outset. After being dropped without warning from the introductory “Testcard” into the menacing “Horizontal Hold”, the listener can make out a chugging, squalling guitar pattern that Mogwai repurposed for their song “Like Herod”. The foghorn drones of the dour “Not Waving” and the experimental percussion of “Water” bear an uncanny resemblance to Phil Elverum’s gloomy freak-folk. “24 Track Loop” could easily pass for a Black Midi instrumental jam. And the piercing pitches of “Diet of Worms” presage Otomo Yoshihide’s noise-jazz excursions.

There are so many direct lines to later musical developments that This Heat could be considered the experimental rock equivalent to Sabbath’s Master of Reality. But where Master of Reality is druggy and cathartic, This Heat is clear-eyed and harrowing; a nightmare vision from within the belly of a failing war machine, best exemplified by the percussive carnage of “Rainforest” giving way to the funerary dirge “The Fall of Saigon”. Told from the point of view of someone trapped in a besieged embassy, it’s a horror story about being forced to eat the office’s pet cat as North Vietnamese troops advance on the city. After the verse concludes, a guitar solo searches in vain for a hopeful note before starting to strum desperately, as if compelled to wrap things up by the unexpected arrival of enemy forces… then the shredding bleeds back into “Testcard” and the transmission ends. What’s most striking about “The Fall of Saigon” compared to other politically charged music of that time period is a complete lack of righteous anger. In a time when most protest songs were delivered comfortably from the moral high ground, This Heat had no reservations about acknowledging their complicity (and, by extension, that of their listeners) in the horrors of imperialism.

Much has changed in the world in the decades since This Heat debuted, but in 2020, now that their discography has been made available to the streaming public, it doesn’t seem like things are terribly different. History repeats itself, after all. Fear of global warming and disease have become the paranoia du jour, with the occasional World War III scare peppered in for old time’s sake. As “The Fall of Saigon” goes, “my God, how we got so far / only to reach so low.” Forty years on, This Heat’s inscrutable sonic aesthetic and uncompromising moral clarity are still fresh, relevant, and necessary. In other words, progressive.