Vaporwave was never meant to last. It would turn up, like a rare butterfly, in YouTube algorithms or Soundcloud playlists, song titles and artist names obscured in kanji. Broken, fleeting and weird, the slowed-down samples would invoke nostalgia and unease alike – a window into another dimension where the awkward transition period between 80s and 90s never ended. And then it would be gone, overwritten by new memories of something more memorable. As the genre became a documented phenomenon, brief flashes of beauty became more tangible, took a form and created an entire aesthetic of its own: a candy-colored and marble-laced variant of Mark Fisher’s concept of Hauntology, a transgressive manipulation style of disposable muzak that united the post-human with the deeply emotional.

Where the genre’s first forays consisted mostly slowed-down and chopped-up 80s kitsch, new producers turned albums into entire narratives. A day at an imaginary mall, a stroll through the looping muzak of a post-apocalyptic city, the sounds of a Cyberpunk metropolis, the found videotape of a Videodrome-like channel, a world where 9/11 never happened. Like urban myths, those works spawned imitators and expansion, sequels and rip-offs, until there were as many sub-genres as artists working.

During those days, the mysterious Computer Trilogy, released between 2013 and 2014 by a producer labelled Infinity Frequencies, rose to notoriety. The three albums, chronicling Computer Death, Computer Decay and Computer Afterlife and mostly consisting of short loops, managed to fuse an eerie sense of imposing dread with angelic, pseudo-classic compositions. The dark, bass-heavy drone of the production suggested the samples might be remnants of videotaped commercials, evoking a late-night mood that shifted between the romantic and horrific. The internet soon found a label for the style that united late-night variety of vapor: ‘Broken Transmission’.

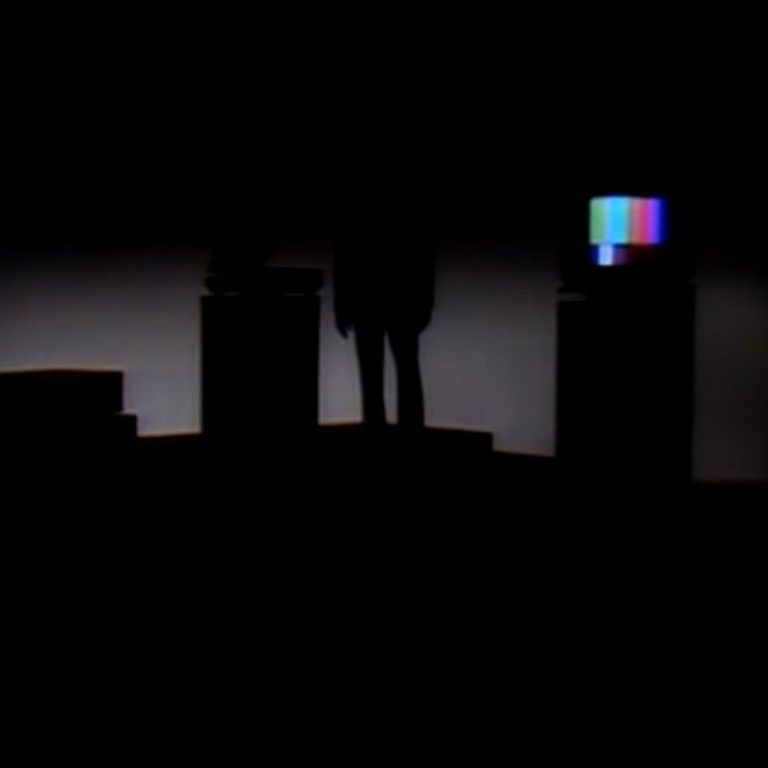

As iconic for the vapor community as it was, the Computer Trilogy would prove to be only a blueprint of what was to come. In 2015, Infinity Frequencies released Into the Light via London’s iconic Dream Catalogue label. The design aspect of the album alone conjured a unique atmosphere, from its suggestive title (both an echo of Siouxsie and the Banshees and a well-worn staple of ghost stories), to the haunting cover art of a shadowy figure framed by a TV’s test-signal, and the lack of any further description or narrative framing. With its mere existence, Into the Light managed to conjure suppressed memories of childhood nightmares and forbidden VHS tapes, of the folklore associated with long-dead media that was only glimpsed during schoolyard whispers, and of lonesome nights in front of cathode-ray tubes.

And then there’s the actual music within the album: 21 hypnotic, seductive, often claustrophobic, and climactic revelations. The ghostly choir of “Following” is accompanied by a digital xylophone, finally rising, only to be cut down again to start from the beginning. The ominous synth-line of “Far Away”, which snakes itself around a Giorgio Moroder-like backdrop and immediately provokes night-time images of a neon-lit highway. The distorted strings of “It was once here” bring to mind the haunted mood of John Lennon’s “Glass Onion”. A female voice in “A cold breath” alternately seems to repeat a mantra of “Come. Come.” or “Cold. Cold.” And then there’s the numerous occasions of voices speaking in Japanese, repeating themselves, all of a sudden dropping two octaves, then rising again by a few notes, only to return to their point of origin.

There’s no ghost in Into the Light’s machine, no little girl that crawls out of a well, no storied past of mysterious deaths linked to its consumption, and yet the album feels occupied by an otherworldly presence, an aura of a past that has long gone by. This interpretation seems an intentional goal. An old media studies wisdom suggests that every new medium’s popularity coincided with the notion that this medium offered a way to communicate with or record voices of spirits. And, as seen with the Fox sisters, the 1992 broadcast Ghostwatch, and The Ring‘s haunted videotape, this idea of mythological embodiment has continued to survive right into our current era of constant surveillance.

It is in the absence of an origin story, in the nameless creator and faceless cover model, in the formless voices that occupy the looped samples where the unease of Into the Light blooms. This becomes especially obvious when the realization sinks in that those samples often harken back to TV commercials, a medium whose seductive, often pseudo-erotic imagery is meant to play to an imagined audience’s desire. Thus, the album broadcasts what would happen if those controlled images of wish fulfilment developed a will of their own, removed all baggage of product placement, and existed in a constant state of never-ending incantation. A cascade of film noir synthesizers, shadows, neon lights, glass pianos spinning around their own axis, a delusional Cyberpunk utopia frozen in brief flashes of a few seconds each, hideous and beautiful. And then, they are gone, fading back into the mist of snowy static, leaving only vague memories.

Therefore, it might seem strange that the Illinois label Forgot Imprint decided to catch the ghost in plastic and give Into the Light both its debut on vinyl and a cassette reissue. But, as with all myths associated with media, the viral qualities of the work itself were just too precious to fade away in a sea now occupied by dozens of Broken Transmissions that came after it. Its banishment from virtual artefact into physical relic has only made it more mysterious, its initial run of copies gone in minutes, leaving genre fans bemoaning its scarcity. Even when finally given a form, the spectre remains as elusive and intangible as vapor.