As Mandy, Indiana release their debut album, our man in Berlin, John Wohlmacher, goes long with vocalist Valentine Caulfield about liminal spaces, oppressive regimes, horror movies, the Paris catacombs and more in a wide-ranging conversation

“Oh you’re in Germany, I’m gonna move there soon!” Valentine Caulfield’s smile radiates warmth and comfort. In stark contrast to the sharp edges contained within the songs of Mandy, Indiana‘s debut album i’ve seen a way, the vocalist’s genuine personality and quick wit reveal a sense of deep humanity and empathy. When I mention our country now has an all new, low-priced train ticket to traverse the entire country, she responds grinning “Of course, why do you think am I moving to Germany?” Later, when I remark I’m genuinely saddened I didn’t have the opportunity to see the group live yet, she explains how gruelling touring mainland Europe has become for British bands, now that Brexit is in full effect, and in the same breath offers an invite to future shows.

Caulfield’s social dedication towards her direct environment and active approach to politics is a leading motif, both in her music and in our conversation. Yet the trained singer – one of the few non-white leading women in the traditionally more white-male landscape of guitar-driven music – isn’t following the blueprint of angry sloganeering so common nowadays. Dancing on the landscapes of sharp glass and concrete that make up the nocturnal beats and noisy guitars of Mandy, Indiana, her french-language lyrics become an element of performance of themselves, at times resembling robotic voices giving sinister commands, only to replay the anguished screams of a torture victim in another place. Seemingly following a logic all of her own, Caulfield sings like no one else right now – or before her.

As our conversation moves along, past political observations and explorations of the horror genre, it becomes clear her gaze is directed towards the future, making an earlier discussion about the classification as Futurismus all the more poignant – even though (or maybe especially because) Caulfield elaborates on the group’s urge to defy all kinds of classification or description, leaving labyrinthine structures of cryptic suggestions and cinematic tension to be explored by their audience.

It almost seems as if Mandy, Indiana just appeared, out of nowhere, fully formed, a comet that just hit Manchester and invaded the airwaves like an alien species with their biting sound and memorable songs. In reality, the band goes back to the era of the long lockdown, as Caulfield explains: “We actually took quite a while to release anything. Scott and I started to play together in 2018, so over a year before we released anything. There was a lot of trial and error and we abandoned a lot of songs on the way, so we went through the research and development phase. We had a few songs that we worked on that kind of evolved but didn’t feel right. We started this project with the idea we wanted it to be something that we would be proud to put out and be able to stand behind everything that we did. It took a little while, but by the time we released music we had quite a clear idea of what we wanted to do.”

Speaking of style, your sound unites elements of post-punk, techno, industrial and no wave in a very organic way that is hard to classify. I’ve noticed there’s similar developments with other bands occurring parallel, such as Gilla Band or Model/Actriz. It’s this somewhat brutalist sound, I personally lean towards calling it “futurismus”, due to lyrical and aesthetic themes it has in common with the visual art movement. There’s observations of societal dehumanisation, this marvel at technological progression and shades of post-humanism. But I recognise that’s an outside perspective.

Valentine Caulfield: The term we use that resonates the most is “experimental”. A lot of people call it post-punk or electronic, and there’s elements of that but it’s not exactly right. There’s lots of different influences when it comes to the music that we make, and it’s not easy to be pigeonholed as a band. The way we’ve always worked with this project is that we want to keep it moving at all times, there’s no ambition to just be one thing. It would be doing the music a disservice if it’s put into a category like post-punk or post-techno, which I like, or futurismus, which I also like. It’s not something we want to have defined in that way because we don’t plan to be keeping it static. It’s more interesting to us to think of our music as something that is forever in movement.

You were saying there’s elements of visual media – that’s something that Scott pulled many of his influences from at one point, and I think in terms of theatre and opera. We are also obviously influenced by the world and society we live in. It’s not something we want to define because none of those things are set in stone.

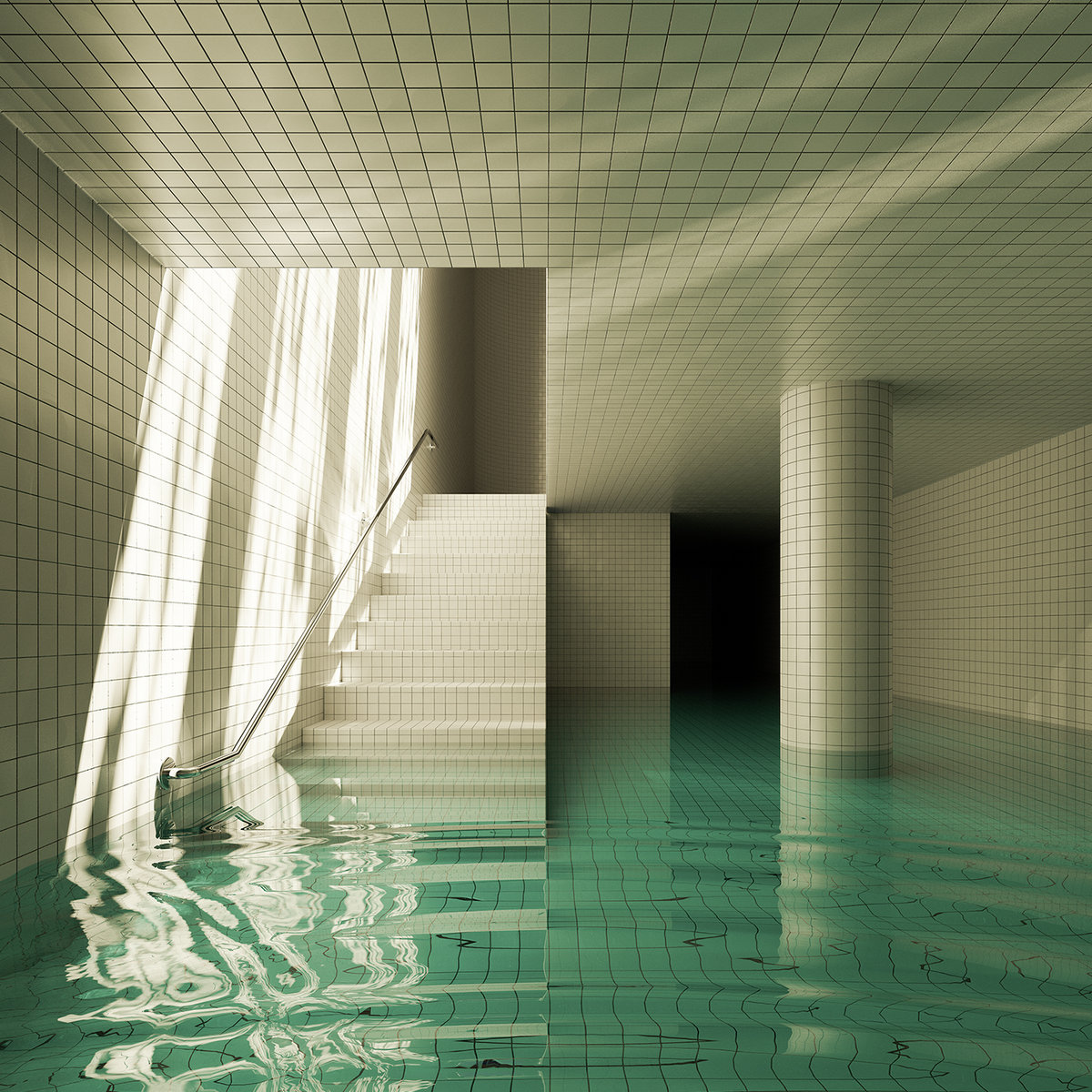

The record opens with something that’s genuinely cinematic: the sound of falling rain. Water is a recurring image on the album, both aurally in songs and with the cover art.

I couldn’t even tell you where the inspiration came from. But parts of the album were recorded in a cave, with an underground lake. All of the analogue gear had to be carried there and set up a full drum kit and generator in this cave just outside of Bristol. Scott was saying how, even with headphones, they couldn’t check what they were recording because of how loud it was. So it could have been a very expansive mistake, but luckily it worked out. (laughs) And then halfway through the recording session, a cave diver just came up from the lake and was kind of, “What the fuck is going on here?” (laughs) So if you’re diving, underground in caves, which seems to be a terrible fucking idea…

YES, yes!

It’s my idea of hell, I’m tremendously claustrophobic! But I think that’s the inspiration for the opening track, “Love Theme (4K VHS)”, and is this image of somebody just showing up in this weird space, and being phased with all of these weird things happening. That inspired a lot of the water, but it also aims to take you on… I don’t want to say “journey”, as it’s a simplified term and the album isn’t a unified piece of work, but there’s this image of going underwater and coming out in this space. And the album was also inspired by the idea of liminal spaces and finding yourself in these creepy spaces that don’t feel quite right. That’s what’s behind this idea of going underwater and coming out into this space.

I actually think the rain sample might have been donated to us by Joe Jones, the recording engineer who did all the drums with Scott. He is really into field recordings, and some of those he donated for the album.

I want to dive deeper into the imagery of liminal spaces. The cover of the depicts the dream pools, associated with the internet subculture around the backrooms mythos. And the idea of spaces creating a musical parallel is something very current. There’s all of those discussions on social media and comment sections where people ask “What music do you think is playing in The Backrooms?” I know some of the videogames based on the mythos have their own music that try to adapt the ominous atmosphere as a soundtrack.

Scott was more aware of it than I was – I’ve seen it on Reddit, but that’s not quite my space. I think the concept ties quite well into the kind of music we make. There’s this element of getting people out of their comfort zones and pushing people to their limits, so it was something we were interested in when Scott mentioned it during the making of the album. You can also find some of this in the lyrics. By the time we were discussing possible directions for the album art, we found this artist Jared Pike. The cover is one of his pieces that he slightly modified for us, as well as the artwork for the “Injury Detail” single. They’re all digital, made obviously to look very real which none of them are, which ties in with our concept. I would say it came together through some inspiration and a lot of chance. We were very drawn towards his art when we found it and got in touch, and he was open to licensing some of our pieces for us. I don’t want to say the backrooms were the inspiration behind the album as it isn’t, but it definitely was something we had in mind and were thinking about and definitely played a part in the album.

This new fascination with liminal spaces is also tied to dreams – it’s these rooms that are open which people engage which as if they were real, even though they aren’t, just like we explore realms within our dreams that don’t exist, but they are real to us. And this strange exploratory quality is also found in some of the songs, most notably to me in “Iron Maiden”. It works in a similar modus to industrial or power electronics, where it confronts you with this idea of pain and suffering, but seems to almost have a dream-like narrative to how it develops to a climax.

In terms of narratives, I’m not sure it’s dream-like, but there’s always a dialogue between the songs and the way we record them, and the spaces we recorded them in. That’s why some of the songs were recorded in a cave, and why some were recorded in crypts. We have been working in a way where we’re trying to work in an environment and see what that can add to the texture of a song. I think Scott is someone who works with a lot of textures, so that’s something he’s very aware of – trying to find the right kind of textures for everything.

You mentioned recording in crypts. Earlier you said you’re quite claustrophobic…

Yeah, I didn’t go to the crypt either.

(laughter)

It was a crypt below a church in Bristol. They recorded all of the drums, except for one track, in Bristol. While recording apparently there was a yoga class upstairs, and they heavily disrupted the yogis…

(laughter)

But it obviously has a very different sound to the reverb that they got in the open space of a cave, which very much lent itself more to some tracks, while some songs benefitted a lot more from sounds that were running sideways and not upwards as much. That very much informed the recording process to the point where the tracks were divided into crypt tracks and cave tracks. We also did something similar with the singles, on “Bottle Episode” most of the drums were recorded in our practice room, except for some of the bits we recorded outside in the corridor, and you can heard everything that goes on in the adjacent practice rooms. The rest of the drums were recorded in a place in Manchester, called The White Hotel, which has a tin roof and an old garage that is a venue now. There’s always a very unconscious effort to add the environment into the music that we make.

Crypts are such interesting places. I recently visited the catacombs in Paris and was surprised how peaceful the energy there was – you would figure places like that would house some sort of ominous or sinister aura, especially with how far below the earth they are.

The interesting things about the catacombs is there’s this part you can visit, and a lot of parts that you can’t visit. I remember I had a few friends when I lived in Paris years ago who used to go down there, and you have to have somebody with you who knows their way around really fucking well. Otherwise you get stuck underground and you die! And people used to have parties there. I’m tremendously claustrophobic and never went. I can’t think of anything worse than being stuck underground in a little passageway full of rooms and… yeah, that sounds terrible! But I think some crypts are very peaceful and some aren’t, which is sort of the duality of a lot of things: so long you know where you are it’s easy, but once you’re out in the dark, then all of a sudden it’s not that peaceful anymore, isn’t it?

It’s not! The exiting part of it is also translating itself into other venues, like the peace you feel on a club dancefloor and then the emotional shift as soon as you’ve left the space. “Oh Jesus, what did I do?” On the opposite, once you leave a darkened space after a long time and see the sun is shining and birds are singing, you realise how much nicer it is to the interior.

I was in Berlin this January and went clubbing with a friend, and we went to two places. We first went into Trauma Bar (a somewhat open space with adjacent walkways to a smaller dancefloor – editor), and then a second club that was just this small, dark cube room with lots of red lights and incredibly loud. We were there until 8AM, and in my mind we were still in darkness, and when we came out it was broad daylight – and in that moment, it was terrifying. It felt kind of magical and kind of like the end of my life.

Yeah, those moments have an almost apocalyptic quality. And while I wouldn’t call i’ve seen a way terrifying or apocalyptic, there is this feeling of proceeding from room to room, and the things you witness can be both beautiful and hideous – at times both in equal measures. But what’s interesting is that it never strikes me as scary, even though there are moments that are terrifying. There’s even some really funny moments hiding in between.

From a lyrical point of view, the things I tend to talk about are very much centred around the world we live in and the horrors of it, why are we creating these societies for ourselves. Because we are doing this. We are here, just allowing the world to literally be on fire and allowing governments to treat humans like garbage. So I feel there’s a really dark quality. I oscillate a lot between this and also feminism, growing up as a woman in a world that doesn’t like you for doing that. No matter what you do, you’re not doing it right, and there’s no way, as a woman, going through life not angering anyone – because there’s always somebody who doesn’t like what you’re doing. There’s definitely a lot of horror in the themes that I choose to look at, but there’s also a message of hope. In the sense that, at this point in time, if there is no hope then why the fuck are we here? If we can’t imagine a way we could all come together and make this a better world for all of us, then there is genuinely no point being here.

I have this conversation with people often. On one hand there’s a lot of despair, but then you see uprisings and demonstrations in many countries and different societies. But the contrast is how, let’s say, you open up the Guardian and the headline is centred on Trump and the Stormy Daniels deal, which is this weird dichotomy of impact.

It’s also interesting to look at the UK, where right now you have a junior doctors strike happening, where nurses in the UK went on strike for the first time ever. The quality of life in the UK is dropping so quickly and so badly, to the point where people who were very strongly of the middle class now are having to think about the way they spend their money. It’s insane. When I first moved to the UK and could live in Manchester for very little money. If I now were to move back, I would be really struggling to make ends meet. I think that’s true even for many people who work very stable jobs. I studied journalism and have many friends that are writing for a living and can’t afford a flat anymore, because even when you’re a BBC freelancer you’re unable to put a roof over your head and feed yourself. It’s terrifying and really telling that the UK media isn’t reporting on it!

The media landscape is really strange at this point. In Germany, there’s these media-moguls that run publishers and sort of pose as neo-liberals, even tho they’re definitely neo-conservative or even more extreme in the topics and opinions they voice and print. But when you talk to Gen-X journalists about this, they see this criticism of the landscape as anti-democratic. In France, there’s apparently a lot of pushback against demonstrators, labelling them criminals and rioters, which is a gesture I now recognise in other countries too.

Macron said in an interview earlier this year – after there had been several days of strikes and protests – he saw no anger, just worry. And… no, these are people who are genuinely revolted at how your government is passing measures that they’re passing without democratic vote, pushing everything to the parliament. The political class has been allowed to bury its head in the sand for a very long time and there’s definitely a portion of the media that is allowing that to happen, reporting that everyone that is protesting is a ‘rioter’. Effectively if you look at the people who don’t support the pensions reform the French government just passed, and overwhelming majority is against it. People understand that, pushing the legal retirement age back to 64, means that a lot of the lowest paid workers are never going to retire, because many of them don’t make it to 64.

But also, criticism of the media has been co-opted and used by many bad faith actors, and you know… that’s not helping anyone.

The world certainly seems to push itself more towards a dichotomy of good vs. evil. It’s hard not to fall into the trap of suggestive terminology, but then you see older generations kind of argue “Why would anyone lie to us?” It’s a somewhat privileged platform of just digesting information that is told to us by an authority, instead of finding a dialogue with people who might not quite be like them, and have differing experiences with the world.

Exactly, but it’s hard for people to understand there are differing experiences out there, and just because you experience it one way doesn’t mean others do too. Especially when the BLM movement took off in the US, there were a lot of white people arguing “but if you haven’t done anything wrong, you don’t need to worry about the police”, which is demonstrably not true. As a white person who hasn’t experienced that, you are WAY less likely to experience that, because traditionally and historically, the police is a racist institution.

Not to mention the prison industrial complex. In a way, we need a way to confront crime, but prisons don’t really serve the function of rehabilitation, or re-integrating people into society.

The biggest creator of crime is poverty, and when you solve poverty you solve, by definition, a lot of incarceration. It’s obvious that it’s a system that works for a lot of people, especially in the US where there’s a prison industrial complex. It’s obviously an interesting question, but the most humanist way of looking at it is to allow all people to have the means to be alive and have dignity, and a house and to feed themselves, by definition you take crime away from them. And then I think all white collar crime should be punished by making people work at McDonalds for minimum wage.

(laughter)

Nothing will fucking reform a banker as quickly as having to work a horrible service industry job!

Talking so much about the horrors of politics, and in relation of horror within some your music, I would like to return to the topic as a genre: what’s your favourite horror-fiction?

Like films or…

Well, horror can be very subjective – some people consider certain horror films as comedies, while to others, films who are barely adjacent to the genre are their most frightening viewing experiences. It’s kind of, what’s the ultimate horror story? as a unique experience to each person.

I think that’s really interesting… I know it’s slightly controversial to name it, but I think my favorite horror film is Rosemary’s Baby. It’s something I’ve got a lived connection with as a woman, it’s genuinely horrifying and it’s something I think I talk a lot about in my music as well, but… (pause) I think there are untold horrors in how we treat women in society. And as somebody who suffers from certain health issues, navigating the medical field as a woman is genuinely frightening! I think I had my single most horrifying encounter with anyone ever last summer. And it was with a doctor. And she was a woman.

Oh god…

And she completely disregarded what I was telling her and made a diagnosis in her head. And I explained the condition I’ve been treated for and she went “NO, this is not what’s going on, THIS is what’s happening with you”, basically trying to have me take some really strong antibiotics to treat a condition I know I didn’t have! I convinced her to do some tests firsts, and sure enough I didn’t have what she thought I had. It’s just one example, but I think it’s one of the things that are disregarded so much because – once again – many medical professionals are men, and even many women doctors don’t listen to their patients even though they don’t know what’s going on. I’ve had so many friends tell me of them being left in genuine pain because doctors wouldn’t listen to them… I think that’s definitely one of the things I look for the most when I look for horror, and why Rosemary’s Baby is my favourite horror film, even tho Roman Polanski is a piece of shit.

Given the origin story of the drum-takes on i’ve seen a way, and your political inclinations and penchant for the uncanny: have you considered recording your vocals in a prison?

I’m interested in those kind of places, but it’s tricky for moral reasons, unless it’s an empty prison, where you don’t have as many moral issues to it. But they’re obviously very historically charged places, but I wouldn’t want to disturb people that are having all of their freedoms taken away from them. I’m not imposing my weird music onto people who don’t really want to listen to it.

But then there’s also this parallel between art and incarceration – Mikey Piñero comes to mind, who was a drug dealer who became interested in writing while incarcerated and ended his life as a poet and playwright. Once freedom is taken away, art acquires a new purpose.

But it also says something about the way how when you’re in this place for a certain amount of time and you don’t really have to worry about how your next meal is coming on the table, many people turn to art.

I want to return to the aesthetics of Mandy, Indiana. You sing in French, which is a language unfamiliar to many audiences, especially with how common English is in the music worlds. Given your interest in politics and confronting audiences, I was wondering if this element is an intentionally confrontational choice.

It was one of the starting points of Mandy, Indiana. Scott and I met because we shared a bill with our respective previous bands, supporting this Newcastle band called Moses, great two-piece. My previous band was fairly classic, and we had one song in French and Scott said he was interested in both how I performed on-stage – which… I guess I do my thing – but he said he was also very interested in the use of French language, as it forces you to do a lot more work to get the intentions of the person talking to you in this foreign language. So it was something we were really interested in doing from the start, and I think it worked very well.

It’s also really interesting because I’ve written and spoken pretty much only in English for the past 10 years of my life. It’s become my favoured language – if I talk to myself, I do so in English. It’s a lot more of a challenge even for me, a native French speaker, to write in French. Not only do I have to craft lyrics that I like and transmit a message, but I also get to use language in a completely different way. I make an effort to use certain consonants and sonorities in a specific way to sort of convey the meaning of the words as well. It’s basically just a completely different way of writing songs: “I’m going to say something to you in a language that you don’t get and I’m trying to pass my intentions to you in the way that I perform and in the way that I use those words and let’s see if you can get some of it.”

How would you describe your live performance style?

I studied classical music for a long time and was a lyrical singer growing up, performing in choirs since I was five or six years old and starting in music school when I was 10. I did lyrical singing and also a little bit of opera. I enjoy all that a lot and I think it informs my performance in the sense that a lot of operas – I suppose it’s not a thing for you because a lot of them are in German…

(laughter)

… but a lot of classical traditional operas, coming from France, I wouldn’t understand the German. I sung so much in german when I was younger, and spoke the language fluently until I was 17, and then I’ve moved to the UK and haven’t spoken the language in such a long time. And now I was in Berlin for all of January, and I could just about order a coffee and I felt really bad. It felt like such a victory when I went to a shop and said something and the other person replied back in German, it was like, “YES!” Because usually I’d say something in German and the other person responded in English and I was just…

There’s a certain ridiculousness how language works here…

But yeah, back to opera, I think getting meaning across comes a lot more through the performance and feelings and emotions and theatricals you put behind the performance. So that informed a lot of how I perform, because most of the audiences I perform to don’t understand what I’m saying, and I want people to get at least a taste or idea of what I’m saying. So it goes a lot more through the motions of what is more similar to opera than a lot of post-punk or techno music.

It’s also funny because in the process of translation, you find those hidden meanings, such as in “Drag [Crashed]”, where you sing: “C’est plus jolie / Une fille qui sourit” (“It’s prettier / A girl who smiles”). It sounds so sweet, but once you’re getting deeper into the song’s lyrics, you figure out there’s this hidden trap door.

It’s always funny as well, because when we started people would always say “Oh, French, one of the great romance languages!” It allows me to create stories that are genuinely hard to make palatable. Because it sounds so nice, but then you dive in and… with “Nike of Samothrace” for instance, which was one of our early singles, it’s about stabbing a rapist. And a lot of people were surprised when they found out – and don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating for stabbing anyone – but for that story to translate in a way that was so, to many people, kind of lovely, was very interesting to me. I suppose a lot of people who don’t speak French think that it makes everything sound nice, and that allows me to go “Well, you’re trying to attack me on the street and now I’m gonna stab you, what you gonna do about it?”

The song titles seem to communicate some of those hidden intentions, yet they’re also somewhat codified on I’ve seen a Way – there’s leetspeak, emojis, I think also an age classifier… It’s all very modernist.

Well, I’m really going to disappoint you here (laughter) because Scott was the person to pick all of those song titles. I remember picking the first two song titles of our singles. “Berlin”, for example, was written after my experience of clubbing there, thus it just remained as “Berlin”. But ever since then it’s always been Scott’s choice – “Alien 3” was originally called “Sledgehammer Scalpel”, which I repeat in the lyrics, in French. But then when it came to actually give it a title, it became “Alien 3” because for some obscure reaosn, Scott was thinking of the Alien 3 Gameboy Game, and then everything since then has just been his spur of the moment idea, and we’ve kind of kept going with it. (laughter)

So I’ve discovered them as I’ve discovered the tracks. It’s kind of become this ongoing game of “What is Scott gonna come up with next?”

But that’s brilliant, I’m always fascinated by bands who involve a hint of mystery in this process. I’ve interviewed bands and asked about certain song-titles or elements of their work, and the response is “Oh, that’s this one member’s choice and none of us know what it actually means.”

(laughter)

I think, honestly, it wouldn’t surprise me that if, in 10 years, we would find out there’s a massive easter egg hidden in i’ve seen a way, especially with Scott, but I trust the process. At the end of the day, I’m also the person with the ability to hide the more I work – it’s not like anyone is going to understand what I’m saying…

(laughter)

I think it’s nice that we keep that part of playfulness in there, and I think we are a group of people that really hate this idea of band names, album names, song names. So I think just giving them very little meaning… I don’t want to call it an artistic pursuit, because that gives it way more agency than it has, but there’s definitely an urge of “I don’t want to name my song after what it’s about”, it’s just much more interesting to not do that.

It’s kind of like with manifestos, who attempt to destroy the rules of art but then end up becoming a rulebook themselves, an almost cannibalistic process. We try to evade those things and end up finding something else. For example, I sensed there’s a reflection on internet culture both within Mandy, Indiana’s artwork and the song titles all the way to the earlier band name change from the initial “Gary, Indiana”.

Let me just address the name change first – it’s not a very interesting story: our label is based in the US, and they recommended to change the name. But when it comes to the internet – I think our creative process is reflective, but not in the way that we’re looking at the past and take influences from it, it’s a lot more interested in reflecting what is going on right now. I think there’s a real urgency in what we do and it’s true both musically and in the lyrics as well. We take influences from everything, but mostly what we see, hear and feel in the very moment. For example, the guitar in “Bottle Episode” was originally a sample of a flood siren near where Scott lives, and he recorded it and built the track around it, and then he ended up recreating it on his guitar.

That’s also the reason why there’s so many field recordings and sounds that make up layers and textures on the album. I think when it comes to the internet, it’s easy to see everything being thrown back at you and have a like a pool of ideas, and try to remake of what’s already there. It’s kind of terrifying the way how Hollywood has been doing that so much recently – every time you hear of a film they’re going “We are remaking this! We are remaking that!” We have so much access to everything that happened before us that it’s so easy to want to redo what’s already be done. And I think our creative process goes a lot more through observing what is going on right now and ask “where can we go with this?” We try to not look at the past and what’s come before us – we are trying to go towards the things that are in front of us. So in short, I think the internet has the potential to be both a utopia and a dystopia. Though I think everything is just dystopian right now…

I suppose there’s a lot of portrayal of the left – especially in mainstream media – as a bunch of fucking hippies that go “Let’s give free money to everybody!” and… it’s sad to me how many people would be so much better of if we developed more leftist policies, but they aren’t able to realise that because of big slogans that frighten them, a la “White Privilege”… A lot of people that are clearly bad faith actors are trying to put us all together. Dividing and conquering has worked for centuries and that’s why the working classes still haven’t realised that if we worked together, we could very much get something better for all of us, but those in power want them to believe the immigrants next door is the reason why your life is so shit when it’s not: it’s the banker!

Mandy, Indiana’s debut album i’ve seen a way is out now on Fire Talk – read our review.

Follow the band on Bandcamp, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.