I don’t believe in change, but I trust in transformation. Death is not an end, but rather the beginning of something else, something distant but also something sublime. When Andy Fletcher passed away a few days ago, I was busy filming for a project inspired by Anton Corbijn’s work, blasting Depeche Mode throughout the day. When we had wrapped and took a breather, we saw the news: the glue that tied the band together for so many years, the stoic voice of diplomacy between two gigantic egos, the calm and reassuring presence of one of music’s most famous ‘silent’ members had gone. Andy Fletcher would always joke that he was “just along for the ride”, but it was him that was taking care of managerial issues and keeping the spirits up, settling the tidal shifts and balancing the scales.

Transformation means that nothing is ever lost, but also that everything that grows is already contained within the seeds. How else could I observe this bunch of insecure british teenage boys, draped in gay fetish gear, singing “I want to hold your hand”-bullshit, become one of the most exciting, intricate and daring groups of the 20th century? When Depeche Mode started, they were pretty much a Boyband, a bunch of good looking, synth playing kids that virtuoso Vince Clarke could mold into a teen fantasy, only to leave them after one short pop album. Derided as a joke by their gloomy contemporaries, but with a mega selling hot behind them, the trio soldiered on, and after releasing the undervalued and gloomy A Broken Frame, they found a new creative collaborator in Alan Wilder, who brought bombastic majesty to Martin Gore’s melancholic balladry. With each coming album, the group would build upon themselves, dare to go larger, faster, harder. Love songs soon became more sexual, british middle class critique soon turned to a full on embrace of substance abuse.

Entering their climactic period, Depeche Mode united coal black darkness with the shining light of a thousand spotlights. Their music became the embodiment of co-dependent relationships. There’s the lascivous play with subliminal SM mythology (“Let me hear you speaking just for me”), the overbearing power of drug addiction (“Promises me I’m as safe as houses / As long as I remember who’s wearing the trousers”) and religious fervor turning to domestic idolatry (“Lift up the receiver, I’ll make you a believer”). There’s a constant struggle between naturalist romanticism, spiritual and religious pondering, dark sexual energy of the sounds and movement of naked bodies, the brutalist structure of big city skylines and the crushing nihilism of modern life.

As the machine grew larger and larger, the pressure built. Dave Gahan moved to Los Angeles and started doing Heroin – he came back from death’s doorstep so many times, the local first responders billed him “The Cat”. Gore started to drink, burying himself in his melancholy. And Wilder departed, exhausted from the grind. But Fletcher would pull the opposing magnets Gore and Gahan back together, support their sobriety, and carried them through their dark ‘90s era and some of their most interesting albums. Looking back, there’s many comparisons from that era that feel apt. “The Beatles, but with synthesizers” – starting out as a simple boy band, then embracing american and psychedelic influences to become the largest british band of their generation. “Roxy Music, but in black leather” – comparing their romanticism and Gahan’s libidinal aura versus the androgynous paradise bird Gore to Ferry and Eno. “Coil, but heterosexual” – linking their mystical qualities to their ambivalent, borderline aggressive rabid dog melancholia to that of the Industrial occultists. Or simply: “U2, but in good”.

Later, it would become a little quieter around them, as the band released records after long gaps, their live shows now mass events the size of Rolling Stones concerts. There were hushed voices Alan Wilder had rejoined them in the studio, a promising rumor, but all of a sudden, “Fletch”, the man who stood in the background as the spine of this magnificent body, has parted, and we are left mourning. As always in these situations, the BPM staff has come together to pay homage to Fletcher by writing about the Depeche Mode we love, cherish, that keeps us awake, that we drank to, danced to, fucked to, prayed to, that unites our sacred and profane. Because in this music, he’s still with us, smiling quietly, nodding while two majestic cocks lose their feathers fighting in the forefront, telling us that all will be OK. Wherever he is, whatever he has transformed into – I hope that he enjoys the silence. – John Wohlmacher

Honorable Mention:

When contemplating the many great works of Depeche Mode, their 2013 release Delta Machine isn’t necessarily the most obvious one that springs forth, yet one that should be appreciated regardless. Entering a new decade, this album proved that the band hadn’t remotely exhausted their creativity. Delta Machine contains all the striking components of the Depeche Mode canon – void-black synthscapes, Dave Gahan’s icily emphatic vocals and romantically sinister lyrics – yet descends further into darkness. With production assisted by Flood, the beats are more alarming, the synths urgent and slithery and the overall feeling of dismalness quite amplified. From the lurching, ominous opener “Welcome To My World” where Dave offers to “penetrate your soul” and “bleed into your dreams” to the waltz-y “Angel” that, for all its vivid talk of enlightenment, can’t quite minimize the feeling that there’s an auction for your soul, the album situates the listener in a great juxtaposition of groove and doom. If you are not familiar with this underrated gem, please direct your ears to the incredible album cuts “Broken” – a catchy ode to being for someone during their darkest time – and “Alone” – a haunting track whose production feels like a classic video game soundtrack where you’re destined to never win despite your best efforts. – JT Early

Our Favorite Five:

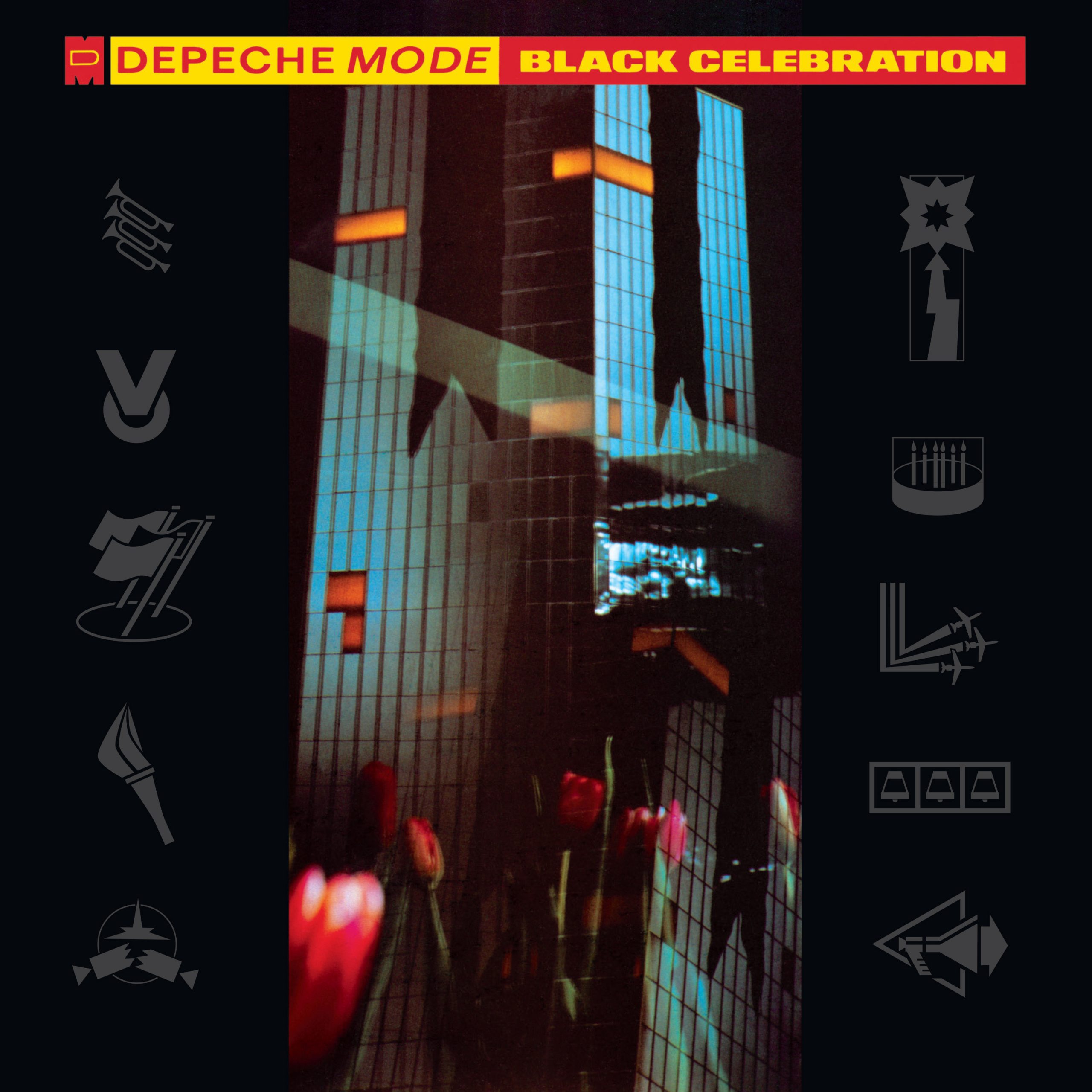

Black Celebration:

In all honesty, I wasn’t overly familiar with Depeche Mode prior to Andy Fletcher’s passing (the other writers here are far more qualified to pay tribute, I’m sure you’ll find). I’d heard, of course, Violator and Music for the Masses, but there ended my knowledge of the band. I decided to plunge in and listen to their discography, in order. Gradually emerging as my favorite of the bunch was the album just prior to their two biggest successes: Black Celebration.

Its title suits it perfectly, with the LP feeling like some macabre dance party to which you’ve received an exclusive invitation. The album found their sound ever-blackening (with no play on its title intended), as they refined their sound into a crystalized, opaque, ominous gathering. It deals with the themes with which they often found themselves obsessed: sex (“A Question of Lust”, anyone?) and power, with less hostility towards faith, and a greater focus on sheer despair and jaded anxiety (“It Doesn’t Matter Two”).

The music expanded and unfurled along with their expanded ambitions, blips of melody and perfectly jagged soundscapes complimenting their morose excursions. Veritable walls of synths accompany their every move, more layered than on any project prior. There’s the ticking clock of “Here is the House”, the anxiety-inducing, bubbling choir of the aforementioned “It Doesn’t Matter Two”, the threatening chug of “Stripped”: you name it, each track has some newfound way to unsettle you. Somehow underrated upon its initial release, it’s since been lifted to its rightful place: towards the very forefront of their discography, not to mention towards the very top of the decade of its release. As influential as it is essential. – Chase McMullen

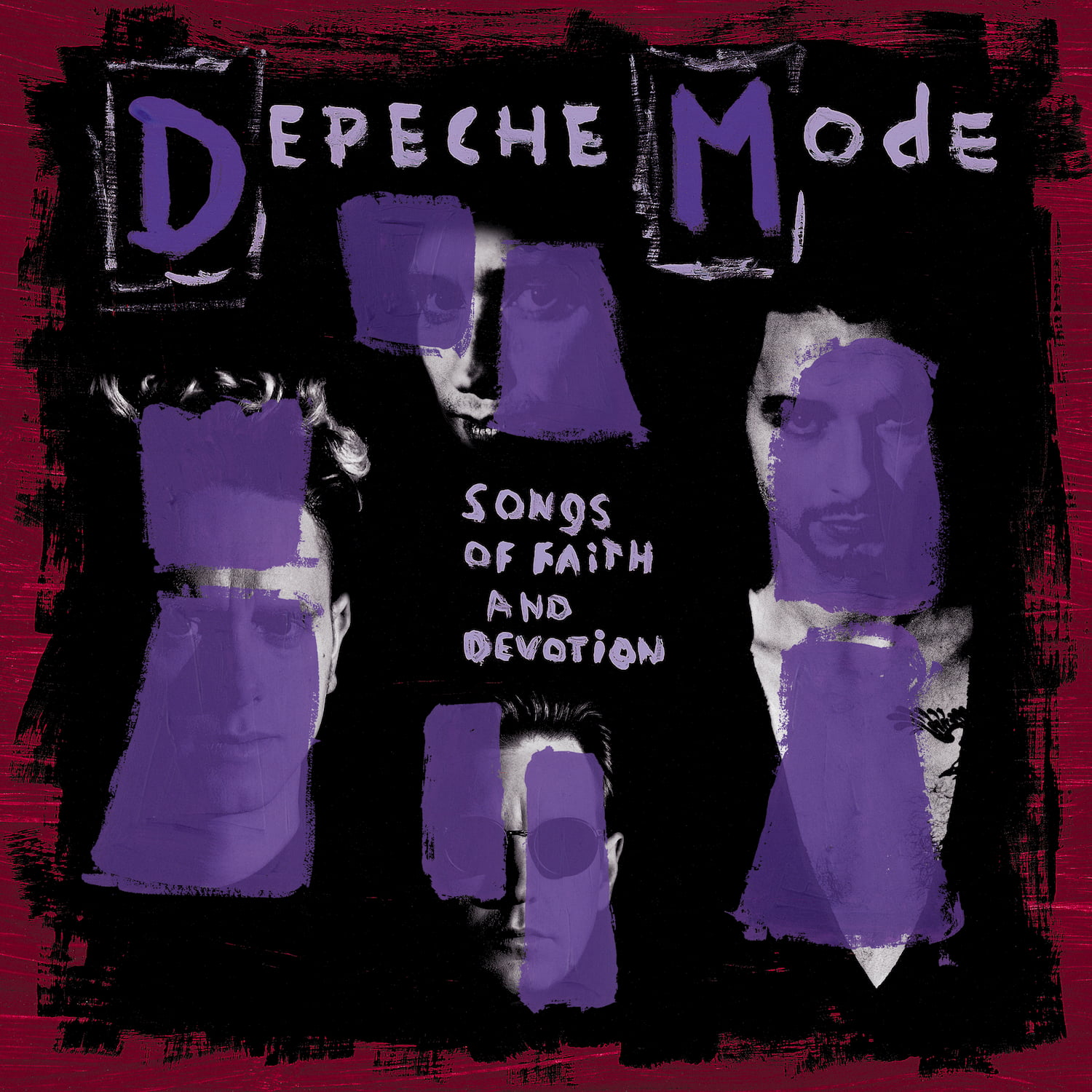

Songs of Faith and Devotion:

Following what is arguably the band’s most heralded and iconic album Violator must have been an intimidating prospect yet 1993’s Songs of Faith and Devotion proved another masterpiece in their discography. With way more variation in sound and style, Songs entered many realms such as alternative rock (“I Feel You”), theatrical baroque pop (“One Caress”), twisted gospel R&B (“Get Right With Me”) and cinematic synth-pop with a classical twist (“Judas”) creating an unpredictable and thrilling experience. Every track on this album feels dramatic and maximal and illuminates the versatile capabilities of the band. While still embodying the Depechian darkness, Songs is such a feel-good listen for its experimentation and surprise. The highlight of this album – and what Dave Gahan considered the best track the band have ever done during an old interview with Simon Amstell – is the dramatic gospel track “Condemnation.” The raspy and passionate vocals of Dave, the layered, harmonic choir-like backing melodies alongside the echoing, simplistic drum patterns and soulful piano, automatically make this song a standout. While gospel tracks are usually affirmative and righteous, this plaintive ode is sung from a sinner’s perspective (“Condemnation…/Why?/Because my duty was always to beauty/That was my crime”) and proves a beautiful exercise in subversion. While not remotely the most traditional Depeche Mode record, Songs of Faith and Devotion easily joins the oeuvre of iconic alternative albums released in the 90s. – JT Early

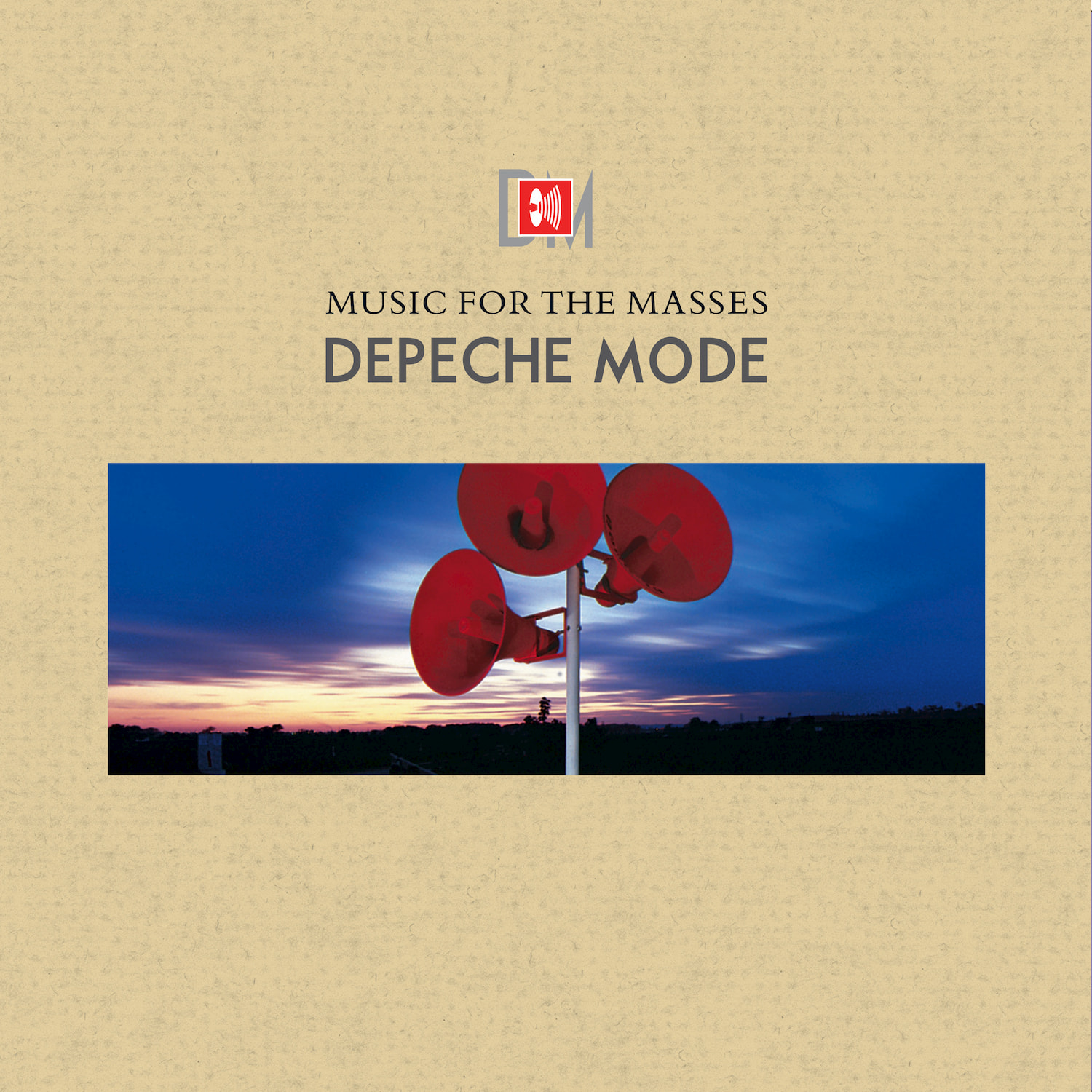

Music for the Masses:

By the time 1987 came around, the chirpiness of early Vince Clarke penned Depeche Mode pop songs had long been forgotten as Martin Gore’s darker subject matter was now ingrained into the band’s aesthetic. A push by their label to record more commercially appealing hits was met by the writing and recording of a dark record with a tongue firmly in cheek title. The songs’ subject matter veers from obsessive love, to drug use, and homoerotic sadomasochism – very likely the exact opposite of what the record label wanted.

There is a grandiose, pseudo-Wagnerian feel to the record as a whole, with “Pimpf” and “To Have and to Hold” being huge in scope. The introspection of the record as a whole made their huge success at this point quite startling, in the same way that Radiohead ‘breaking’ America with Kid A doesn’t quite make sense. It’s the pull of subcultural isolation when so many people see the personal in the product. This has always been one of Depeche Mode’s great strengths, making music that resonates deeply with individuals of a certain mind set (but that would have been a terrible album title).

“Strangelove” and “Little 15” highlight the band’s ability to write pure bangers about risqué subject matter, while “Behind the Wheel” and “Never Let Me Down Again” use the Springsteen style trope of cars and movement to focus on BDSM and drug use. Hiding in plain sight, taboo topics inform the record’s narratives that no doubt go right over many in the audience’s head. – Todd Dedman

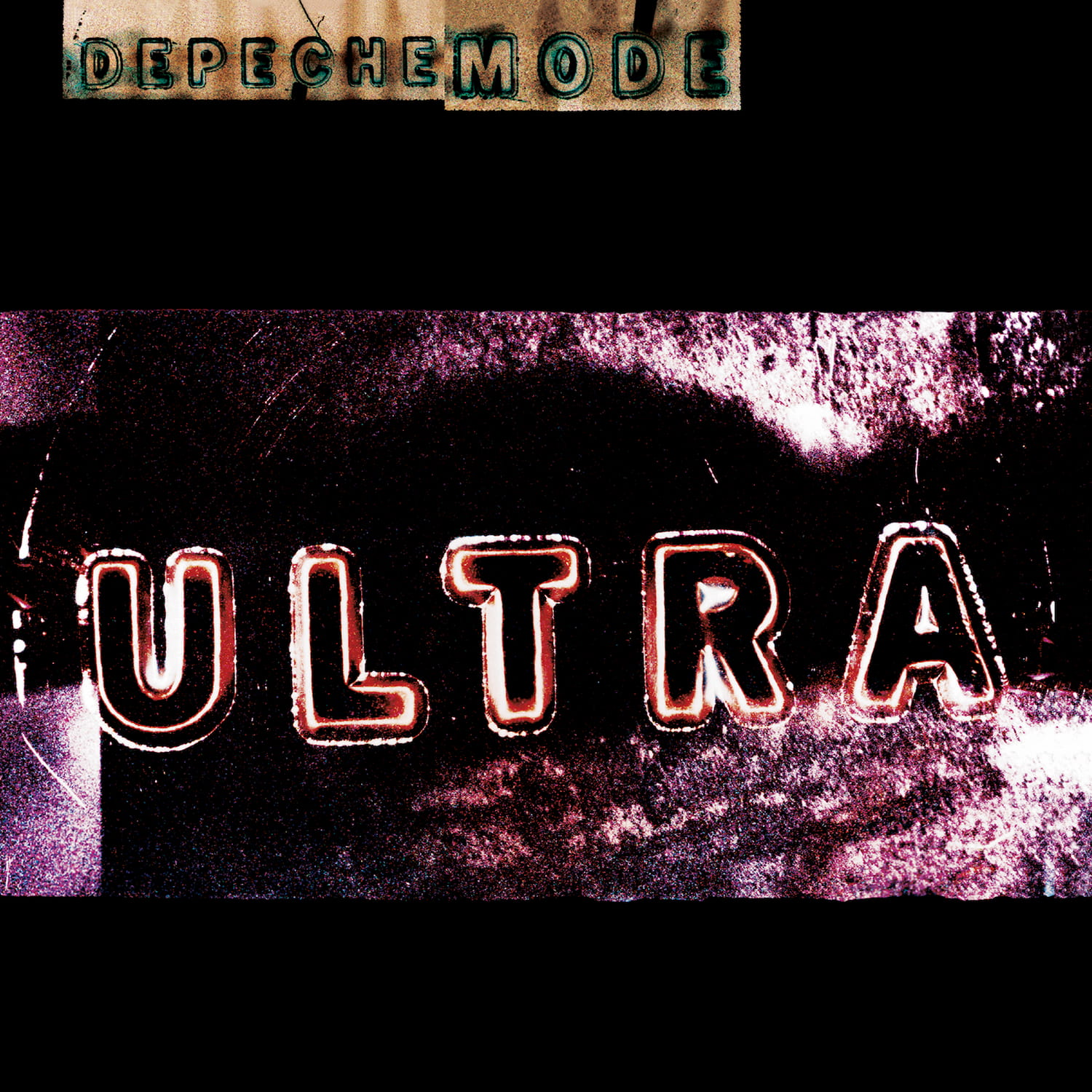

ULTRA:

The sea is a mass of TV static, and the sky is rancid oil. The city skyline is devoid of light, emitting a black glow. The glass-and-metal fronts reflect blue, violet and beige neon lights, advertisements for cigarettes and bars, the two last things left for the shadowy citizens remaining. If Blade Runner’s Rick Deckard listens to Vangelis, then the replicants he hunts listen to ULTRA. It’s just as influenced by Synthesizers, Jazz and Film Noir, but darker, deeper, grungier – a true Cyberpunk Limbo.

There’s many reasons for this dark futurism, devoid of the warmth that made so many Depeche Mode records charming, but the truth is that there was little left of Dave Gahan. In August of ’93, he slashed both of his wrists in an attempt to commit suicide, something he would later characterize a cry for help – in October of the same year, he had a heart attack while performing in New Orleans. He got even closer to dying in ‘96, when following a speedball overdose, his heart stopped for two minutes and he witnessed an out of body experience, in Los Angeles of all cities. “All I saw and all I felt at first was complete darkness. I’ve never been in a space that was blacker, and I remember feeling that whatever it was I was doing, it was really wrong.” The Cat, as paramedics billed Gahan, still had some lives left and soldiered on. Meanwhile, Alan Wilder departed Depeche Mode disillusioned of the music business, just as he had fully embraced the new role as drummer for the band. Everything around lead songwriter Martin Gore was crumbling, so where else could the band go but down?

Ultra imagines a cityscape of grunge and industrial corpses. The former clear cut nocturnal brutalism, characterized by epic hymns and pathos, made way for sleazy synthesizer Rock, the type you imagine played in fucked up Strip Clubs by gross lounge lizards. It’s a world where the sun won’t shine. “Barrel of a Gun” is a fucked up psychedelic journey into Gahan’s self hating heart. Accompanied by a glamorous heroin-chique music video, the song perfectly aligned itself with the gothic nihilism of late 90s MTV iconography. The grim, joyless “Useless” takes it a step further and presents itself as a bitter, sexy breakup negotiation with an air of public execution to it. The accused becomes the accuser as Gahan’s anger melts with Gore’s acidic guitar solo. Besides those singles, the record delves into a variety of incredible genre influences. There’s the atmospheric, Cyber-Ambient of the instrumental interludes “Uselink” and “Junior Painkiller”. “Insight” has shades of a lost Coil track, while “Jazz Thieves” resembles Angelo Badalamenti’s uncanny Audrey’s Dance theme from Twin Peaks. “Sister of Night”, the sensual “The Love Thieves” and “The Bottom Line” connect with Gahan’s sensibilities of Christian romanticism and the spiritual search for love in a carnal world, while “Freestate” introduces a dry desert vibe, all synthetic Country guitars and empty highways.

There’s one moment of sweet reprieve, one safe haven, in the string led, proto-Kid A ballad “Home”, fronted by a yearning Martin Gore – but like everything in Ultra’s barren landscape, it’s merely a façade. Gore uses the song to confide about his alcohol abuse, which he battled while Gahan was shooting H. It’s characterized by beautiful poetry that screams of death desire and self destruction: “Here is a song from the wrong side of town / Where I’m bound to the ground by the loneliest sound / That pounds from within and is pinning me down […] God, send the only true friend I call mine / And pretend that I’ll make amends the next time / Befriend the glorious end of the line”.

This marriage of extremes, of Sex and drugs, overdoses and irrefutable lacks, icy guitars and mechanical beats, is why the record has so often been argued to be Industrial music. There is parallels here to the self immolation of Coil, the vulgar Noir of Nine Inch Nails or the spiritual perversion of Throbbing Gristle, but the trio didn’t commit to those aesthetics because of stylistic exercise or Zeitgeist ideal. They saw their physical forms slowly disintegrate and used music to reflect on this newfound sense of mortality, questioning their spirituality in the process. It sounds like the stuff old men grapple with on their death beds, but as a writer, I can’t help but notice the three were younger than me as I type those words. This might not be the best album Depeche Mode ever recorded – but it is my favorite, and probably not theirs. The band has long left the crumbling city of Ultra, soon moving on to subtropical freeways and business skyscrapers, but they left behind this sprawling architecture of frozen Cyberpunk decay. Some of us still reside here, caught up in the smoked out Strip Clubs and Film Noir Bars that never, ever, close. Skin translucent, hat drawn low over our eyes, weighed down by memories. Thank you for bringing me here, for showing me home, for singing these tears. Finally, I’ve found that I belong here. – John Wohlmacher

Violator:

Violator:

This is the album that took Depeche Mode stratospheric, the moment where visual image and sound perfectly combined to produce the full MTV-satisfying ‘package’. From subcultural monsters to bona fide mainstream stars, the killer punch was “Enjoy the Silence”, a song about quiet introspection that was coupled perfectly by an era defining Anton Corbijn directed video. Dave Gahan is resplendent in ermine trimmed cloak and crown as he carries his deckchair around a host of empty, often desolate spaces. It was arty enough for the cool kids, and just teetering on the right side of ‘not too strange’ for the norms. And, of course, the chorus has the hook of all hooks at its heart.

Violator is the perfect dark hybrid of stadium goth synth pop rock anthems, and is the zenith of the band’s career trajectory before they pushed the keyboards more to the side on the next couple of releases. There is a sense of redemption on the album, with “Clean” seemingly dealing with drug withdrawal and a newfound sense of agency (“I’ve broken my fall / Put an end to it all / I’ve changed my routine”), while “Personal Jesus” is about the benefits of having a saviour as a lover. The latter, fact fans, was inspired by Priscilla Presley’s autobiography, hence the swaggering, hip swaying guitar line which was new to Depeche Mode’s sound at that point.

There’s a raw funkiness to “Policy of Truth” and “World In My Eyes”, while Martin Gore’s best Depeche Mode vocal performance comes in the shape of “Blue Dress” which, in the tradition of Gore’s lyrics, is either perverted or pure. Either way, it’s a cracking track on a truly wonderful record. – Todd Dedman