“Shake it up.”

Those were the first words that most people in the general public heard from singer-songwriter Regina Spektor. The Brooklyn-via-Moscow pianist with a beautiful honey-golden voice, had, after at least five years of working quietly in the underground, finally put out what in her world qualified as a hit. “Fidelity”, from her 2006 record Begin to Hope, provided her a new degree of publicity, of being heard and seen. The song — a poppy, slightly minimalist tune about what it means to love fully and being nervous for such an endeavor — was not her first to make the rounds of music video television blocks; that title belongs to 2004’s “Us”, the sweeping and orchestral pop song from her third album, Soviet Kitsch. But that song didn’t catapult her into the public consciousness like “Fidelity” did.

As a pre-2006 Spektor fan, though, I had my concerns.

I remember knowing the tide had turned when random kids on my school bus were starting to sing “Fidelity” (and other new singles of hers like the peppy “On the Radio”) on the afternoon ride. They talked about how much they liked her, some even using words like “obsessed.” But, in my embarrassingly elitist teen heart, I felt like something had been taken from me. I had barely been an avid music listener for more than a couple years, but I had already established a deep library of ‘indie’ musicians and bands that meant the world to me, and also gave me the feeling like I was in on a little secret that the average kids at my school were not privy to.

Rarely was that feeling stronger than when I thought of Regina Spektor.

Ever since my sister came home from seeing her live in her early days — Soviet Kitsch may have been out at this point, or perhaps about to come out — and brought home a CD-R of her second album, Songs, I was in love. Spektor wrote songs as stories, with narrators and characters and references to books and fairy tales and real-life figures. Her music, ultimately labeled — sometimes accurately — as ‘quirky’, was full of fanciful imagery and unpredictable melodies and lyrical turns. On Songs, she was just as likely to sing about general heartbreak as she was about a particularly special pickle jar. She was just as likely to give us a song with a line like “I see toenails changing colors / Like the leaves of fall” as she was to give us one of the 2000s’ most enduring best and prettiest love songs, “Samson”.

That song got repurposed on Begin to Hope, which was also her proper major label debut, on Sire Records. (Soviet Kitsch had been reissued on Sire before Begin to Hope came out, but was originally put out on Shoplifter.) And so began a neat but potentially worrying trend. “Samson” lost some of its original magic, as it was sped up ever so slightly and given a shiny coat of paint. Up to this point, Begin to Hope was by far her best-produced album, but that also dulled some of the edges of what had made her music so special. And the dulling was, in some senses, almost indefinable: Why exactly was speeding up “Samson” such a detriment to the song? Wasn’t it still a lovely and beautifully-sung ballad?

Yes, but again, something was off. As anyone who spent as much time as I did on ReginaSpektor.net, something got lost in translation. A 21st century bard of sorts, Spektor spent her early years playing show after show in New York, her catalogue of songs expanding to a seemingly endless number of songs.

ReginaSpektor.net — which is, by the way, still a functioning site — was a haven for those of us who wanted more after hearing Soviet Kitsch and, if we were lucky enough, Songs and her debut 11:11. It compiled rarities, b-sides, and countless bootleg live recordings, mostly of songs we had never heard before. It’s where a lot of us first discovered her fan-favorite rare staples like “Loveology” and “Scarecrow & Fungus” and “Mermaid”. The site also gave us our first taste of songs like “Folding Chair”, “All the Rowboats”, “Wallet”, and many more that Spektor would repurpose with slick studio sheen to varying degrees of success or DOA blandness. For some reason, her imitations of dolphin sounds worked so much better in grainy bootleg form than in a coat of sparkling Jeff Lynne paint. (Since then, “Loveology” and the lovely “Raindrops” have also been freshly, properly recorded for her newest record, Home, Before And After, and are much more successful updates of old favorites.)

Eventually, I did find a full copy of her debut, 11:11, and I felt like I was finally there, like I had finally arrived at a place of true connection with her work. Spektor’s debut, now being reissued for its 21st birthday (its 20th was derailed by Covid) and on vinyl for the very first time, is a treasure trove of goodies, a bastion for Spektor fans — new and old alike — to see where she started, see where this quirky and intriguing and eclectic songwriter began her long journey to sort-of-fame. She may be playing huge theaters these days, including a brief stint on Broadway in her own showcase and a Kennedy Center orchestral performance, but back in her early-00s days, she was playing a keyboard in crowded bars, singing songs about porcupines and love affairs and whatever the hell a “caterpillar cousin” is.

11:11 is much jazzier than anything she’s done since, especially in contrast with the stark piano-only recordings on Songs and the synth-flecked baroque pop of later albums like What We Saw From the Cheap Seats, but much of her trademark style is established right on this first album. Opening with the jaunty piano of “Love Affair”, Spektor immediately plunges us into her world. She sings with such gusto, treating lines as disparate as the sly “Festering through an innocent ‘by the way’ / Or ‘have you heard?’” and “He grew healthy wavy brown hair on his head / The kind that babies always go for / With sticky fingers!” with equal conviction.

Accompanied on this album by just her piano and a nimble upright bass, 11:11 remains quite stark in arsenal if not in sound or ideas. “Rejazz” is stripped just to bass, as Spektor repeats the same central verse over and over, giving it more and more passion each time. “Thought I’d cry for you forever / But I couldn’t / So I didn’t” she sings matter of factly, adding in, “People’s children die and they don’t even cry forever.” It’s a brutally direct line, and the song shrugs off the lost love that she thought would rearrange topography and only left her feeling a little hurt. It’s witty but also strangely moving in its realizations, bolstered by its intuitive and restless phrasing.

Then, things get weird, as they usually do on older Regina Spektor albums. On one of her earliest fan favorites, “Back of a Truck”, Spektor takes us on a wild ride. It sounds like an epic piano pop song, like an Elton John song shot through a “What’s Up?” lens and then smashed with a combat boot heel, its piano chords soaring to the sky as Spektor woozily sings about a “sweat sock demigod” and “alien geraniums.” The bridge is especially startling in its fantasy, where the eponymous back of a truck is seen selling various items, like maps, bread, and — oh yeah — a back of a head. Then Spektor asks to buy that back of a head. Then she cries out that it’s actually her back of a head. And then we go back to the geraniums.

None of it, truthfully, makes a lot of sense, but that’s also not really the point. This is Spektor’s version of a stream of consciousness piece of songwriting, the lyrics taking us down a labyrinth with no clear route and no clear exit, and then she gracefully guides us out the same way we came in. It’s a neat trick, and despite its oddity, “Back of a Truck” is one of her most ingeniously-constructed pieces, equal parts pure imagery and potent performance.

Things go back to the ground on “Buildings”, a tale about a husband with an alcoholic wife who causes him great trouble but also great love. She spends the mornings throwing up, but when he gets home from work, the house is sparkling clean and she’s there waiting for him, and “it’s almost as if nothing had happened / And he’ll give her time / And he’ll giver her time”. Later, she “begs” for time, and it’s a heartbreaking ode to relationships that almost work, but for their fissures that slowly grow out of tenability.

The ending of “Buildings” presents us with one of Spektor’s favorite tricks, especially earlier in her career, which is when she mimics a sound effect — an instrument, a production choice, something that would normally be done in post — with her mouth. In this case, it’s a mangled-tape chop-and-screw of key words from the song, but she simply sings it, speeding up and slowing down in thrilling fashion. This tactic of hers probably arose from a lack of funds and fancy studios, but it is something she’s maintained through most of her discography, a trademark she hasn’t compromised on despite the extra cash. (Just check the dramatic gasping on later cuts like “Open”.)

The middle stretch of the album is a mixed bag of oddness and quirkiness. If you are someone who likes your songs light on quirk and camp, then you probably won’t enjoy songs like “Marry Ann” or “Wasteside”. The former is especially outrageous, as Spektor sings about a character (one that would continue to fascinate her for a few more albums) named Marry Ann, who liked her men “in porcupine gloves” so they could make “porcupine love.” Over an active and fluttering bass, she gets as close to selling a lyric like this as likely anyone could. “Wasteside”, meanwhile, is mostly notable for the ending where she stretches the word “sleeping” into about a dozen syllables, in a keening, mewling voice. The song as a whole doesn’t add up to much, but its rubbery exaggeration is fun while it lasts. It also proves a certain fearlessness that was vital to her early work.

In between is a troubling, short tune called “Flyin’”, which details an affair between a student and a teacher. And not only this, but it’s sung over a fist-on-a-table beat, the kind a kid might do on their school desk while someone else freestyles before class. The melody is peppy and singsongy, as Spektor sings lines like “One of them took me with him to sleep / Said not to make a peep” in a near-rap. It’s even suggested, subtly and abstractly, that when this student eventually ends the affair, the teacher murders her (“He sent me flyin’ out of his window… And I’ve been flyin’ ever since / I’ve been flyin’ in the sky”). It’s terribly upsetting if you pay any attention, and I’m sure the dissonance between its message and design are deliberate. Spektor doesn’t do much by accident. She even still performs the song occasionally at concerts, unafraid of its unsettling storytelling.

The towering centerpiece of the record is the nearly eight-minute “Pavlov’s Daughter”, which was by far her longest song until “Spacetime Fairytale” from her newest LP. The song travels through four distinct sections: an opening phase, a slow motion bridge, a reprise of phase one, and a spoken-work coda. The two main phases find Spektor nearly rapping again, this time about a gravedigger getting “stuck in the machine”. (Keen Spektor fans will notice her characters of Marry Ann and the Gravediggers recur through her early work.) It’s told via the character of Lucille (is this the same “Miss Lucy” who owns the sweatshop in “Back of a Truck”?), who wants you to know that she lives downstairs and she hears you fucking your girlfriend. She also hears you masturbating. The middle part is a “Fast As You Can”-style switchup, but instead of minds shaking and shifting, we hear about Pavlov’s daughter (instead of his more-famous dog) salivating on her pillow at the sound of a bell.

It’s a complete non sequitur, as many of her ideas on 11:11 are. Her lyrics follow their own tangents and spirits. As “Pavlov’s Daughter” clatters to a close, everything goes rather quiet. Spektor lapses into a very Patti Smith a la Horses spoken word voice. “It gets quiet,” she sings, and then starts talking: “As quiet as an ambulance staking out the neighborhood / Waiting for the blade to slip and that final blow / But nothing happens, it’s a cruel joke”, her hard enunciation of that two words practically seismic in the space. She ends by slowing her speech, letting syllables languorously fall out of her mouth like stones, as she intones, “Going downstream… To where… it isn’t… even… real… rain… at… all…”

“2.99 Cent Blues” picks up the pace, barreling in all stormy piano chords and bluesy vocalization. The song acts mostly as a fun breather after the wild carnival ride of “Pavlov’s Daughter”, with Spektor singing of buffalo twins and boys from war and the aforementioned caterpillar cousin. Someone is selling stories for $2.99, and ya know what? Sounds like a bargain.

The ending stretch of the album is significantly more grounded than much of the rest of the record. “Braille” is this album’s “Samson” or “Somedays” or “Field Below” — a moment of true, calm, heart-tugging balladry. Spektor tells us a tale of two young parents and the difficulties they face, eating cold soup from cans and playing with matches. One of the song’s best moments comes from a lovely detail about their son: “She hadn’t been a virgin and he hadn’t been a god / So she named the baby Elvis / To make up for the royalty he lacked”. It’s in moments like this when Spektor’s sharpness and deftness with words and storytelling become clear. It rings like a particularly emotional moment in a Miranda July movie — surprisingly moving despite its slightly offbeat nature, creeping up on you. At some point, it becomes clear that the child’s father is no longer here, and our narrator is left blowing out wishes on candles and counting stretch marks on her belly. It’s a heartbreaking song, shocking in its emotional weight after so many kooky and silly songs.

“I Want to Sing” is an acapella jazz tune, with Spektor yearning to sing her lover a song. The way it’s written and sung sounds like a long lost standard, something Etta James or Peggy Lee might’ve tackled. The way Spektor sings lines like “So tell me tell me what / Have I done to deserve you?” or “I should definitely keep my hands to myself” as if the notes are stumbling down the stairs, or the way she sings “Take off your shoes / Take off my dress” with a wink so big it would make Lucille Bluth proud, is a perfect torchy mix of her quirky habits and her love of jazz and blues. She doesn’t need a piano or a bass to make her bona fides clear.

Ending with the sweet and brief “Sunshine”, Spektor guides us to a graceful close. A bright tune where she lends her supple voice to lines as simple as “In the summer I remember days so long and hot / These past weeks it has been raining / And now my song’s a flood”, the song is a perfectly fitting closer to an eclectic and unpredictable album. 11:11 is a bit of a mish mash, inconsistent in tone and scope, but it’s held together by Spektor’s keen eye for detail and clear love of what she’s doing. At any given point, she sounds like she’s having a fabulous time, finally getting to record her stories and put them out into the world.

The fact is, of course, that 11:11 would remain largely the stuff of Limewire legend for many, many years. Eventually, songs made their ways to YouTube — mostly via stray .mp3s and the rare CD-R picked up from a merch table — and by that time, she had already established herself as a versatile and relatively bankable artist. By the time anyone who latched onto the Regina Spektor train via her later albums caught wind of relics like 11:11 (or Songs for that matter), the songs were practically ancient and lost.

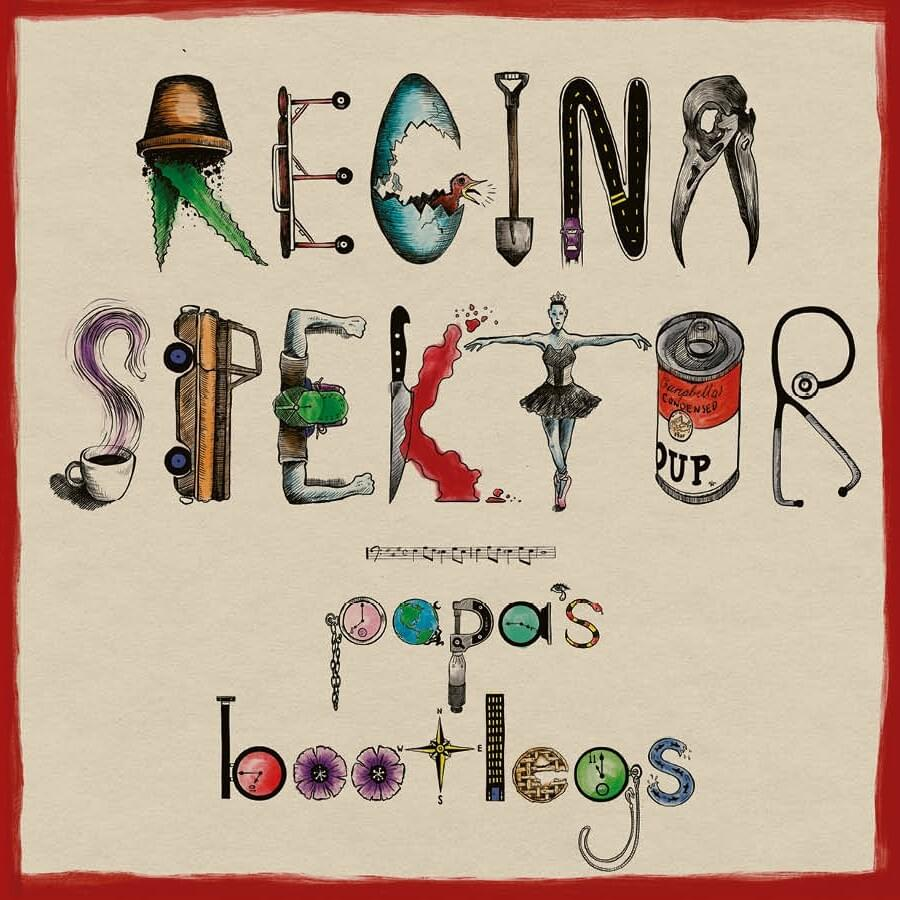

Until now. By putting her debut out on vinyl and officially releasing it for the first time, Regina Spektor is giving her roots the credit they’ve long deserved (and that they’ve long won from hardcore fans). Accompanying the album is a collection of live cuts from her earliest days, called Papa’s Bootlegs, which were kept safe and given to her by her father, who had held onto them for years. The set includes songs from 11:11, but also includes many that even the most ardent fans and ReginaSpektor.net excavators have likely never heard, like “Cyclone” and “Quarters”. It’s such a treat, and it feels especially made for people who’ve been hanging with her since the beginning, occupying equal spaces with her on VH1 and on the music blogs of the mid-2000s. (It’s also a bittersweet accompaniment, as her father sadly passed away in 2022.)

The biggest takeaway from revisiting 11:11 now, 21 years later, is that it is still such a fresh example of who Regina Spektor was, and is, as an artist. It’s a perfect distillation of where she came from, and it’s not hard to see how this album, along with Songs which came out very quickly after, impacted and influenced all her future work. It’s also likely a bit of a reality check, a lesson for those who thought they knew her because they played “Samson” or “Fidelity” a million times. (For the record: I have softened since my teen years on people who discovered her later and/or didn’t spend inordinate amounts of disk space on bootlegs and b-sides. You all are welcome at the party, too, even the girl who told me the song “Prisoners” was “haunting” and abruptly took of her headphones when I tried showing her Spektor’s “earlier songs.”)

Spektor remains a very special type of songwriter, a titan of the New York anti-folk scene who became a quiet force in the pop mainstream, figuring out ways to transform her style for the given moment. She might write a torch song about Billie Holiday on the same album as a song about a “navigator with mappy maps”; she might go from singing a song about a computer made of macaroni pieces to an earnest song about God; she might be just as likely to sing like a jazzy chanteuse or let out a Christina Aguilera-esque melisma; but she gets away with it through sheer force of will and audacity.

And in a way, it’s very telling that Spektor’s biggest push into the public consciousness began with a directive as clear and simple as “shake it up.” At that point in her career, that’s exactly what she was doing: mixing it up a little, a bit of an “and now for something different” as she entered the 2nd phrase of her career. But 11:11 — brash, smoky, indebted to icons of the past, and occasionally awkward or nearly unclassifiable at times — was the start of something new and exciting. And while some may find its quirkier edges cloying or grating, it remains a perfect tintype of this time in Spektor’s career. That it’s also an endlessly puzzling, hugely offbeat, and rollicking good time is just the caterpillar on top.

In the liner notes accompanying the box set for 11:11’s generous reissue, Spektor admits to feeling nervous about revisiting the album. She did so at the urging of her husband — fellow musician Jack Dishel — who thought there might be something there worth taking a look at. She had quite skillfully avoided hearing the songs for years, almost two full decades, out of embarrassment. But when she finally settled down to listen, she found she was less embarrassed and more moved by what she heard: a young woman who worked very hard to make her dream happen, recording quickly in a small studio, almost entirely in single takes. “She experimented and tried and failed,” she writes, “and didn’t care about anything other trying again. And she’s the reason I get to make art as my life now. I’m very grateful to her.” So are we.

The reissue of Regina Spektor’s 11:11 is out now.