“The early stuff – I shouldn’t be such a snob against it,” Joni Mitchell tells Cameron Crowe in the liner notes that accompany a new five-disc box set of her earliest recorded material. “A lot of these songs, I just lost them. They fell away.”

Now, with Joni Mitchell Archives – Volume 1: The Early Years (1963-1967), those early songs have been rediscovered, rescued, and reclaimed for a new audience. A sumptuous package collecting five discs of material that span the first four years of her career, together with a 36-page booklet featuring the aforementioned Crowe interview, photos from Mitchell’s archive, and reproduced press cuttings, this is a mouth-watering and significant first entry in what promises to be an intriguing archival series.

And it almost never happened. Mitchell has always been loath to open up her archives, variously insisting there was little there or that anything unreleased was unreleased for a reason. She dismissed one record company man as a “burglar” trying to get his hands on her tapes, and tells Crowe that she is trying to “beat these leeches to the punch” by curating her own collection.

Mitchell had previously taken matters into her own hands with thematic collections like Dreamland and The Beginning of Survival, eschewing chronology for topical continuity. But, advised by friend and former collaborator Neil Young to opt for chronological order this time, Mitchell completes the project first envisioned by her late manager Elliot Roberts (to whom the project is dedicated) and the result is a beauty. It’s an overdue testament to the magnitude of Mitchell as one of the key composers and artists of our time.

The earliest material, gathered on the first disc, focuses exclusively on the work Mitchell recorded and performed before she wrote any songs of her own. It is stunning to hear Mitchell as the true folksinger she was in these early years; the first nine songs are collected from a set she performed on local Saskatoon radio station CFQC AM in 1963 recorded by DJ Barry Bowman. Immediately apparent is the sheer beauty of her voice – clear, pure, strong. The highlight of these selections is a truly haunting “House of the Rising Sun”, where Mitchell, aged 19, inhabits the melody so completely as she accompanies herself on baritone ukulele, imbuing the lyrics with a vocal delivery that is somehow both innocent and world-weary.

She whips through a set of folk songs that showcase her dexterity with melody and rhythm, from the elegant “John Hardy”, where her vocal style anticipates more of what she would accomplish on her first album, to the frantic pace of “Nancy Whiskey”, where her playing keeps up with the frenetic melody. This early music sounds so vulnerable – “like an ancient world,” says Mitchell – yet there’s a real core of steel there. There is never the danger of her voice going out of tune, of hitting a bum note on the uke. Her performances are robust and emotive and her early playing recalls her later mastery of the dulcimer, with her rhythmic understanding and innate musicality.

A live set at Toronto’s Half Beat club a couple of weeks before her 21st birthday follows, where the confidence is palpable, even with her youthful spoken introductions to songs. She asks the audience to sing along on the lovely calypso “Sail Away”, and there’s already admirable variety in her playing style on Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee”. It’s a remarkable document of a moment in time, a young folksinger a few years away from true greatness of her own, singing folk songs on her baritone ukulele on a Yorkville street as noises pour forth from the audience (on “Maids When You’re Young Never Wed an Old Man”, a snippet of which previously appeared in 2003’s documentary Woman of Heart and Mind) and where the coffee machine hums during her a cappella (complete with Scottish accent) “The Dowie Dens of Yarrow”. Even at this early stage, Mitchell curated themed sets, and, as she attests in the liner notes, there is a confidence and comfort here among the coffeehouse audience that she struggled to replicate as she graduated to halls, theatres, and arenas later in her career.

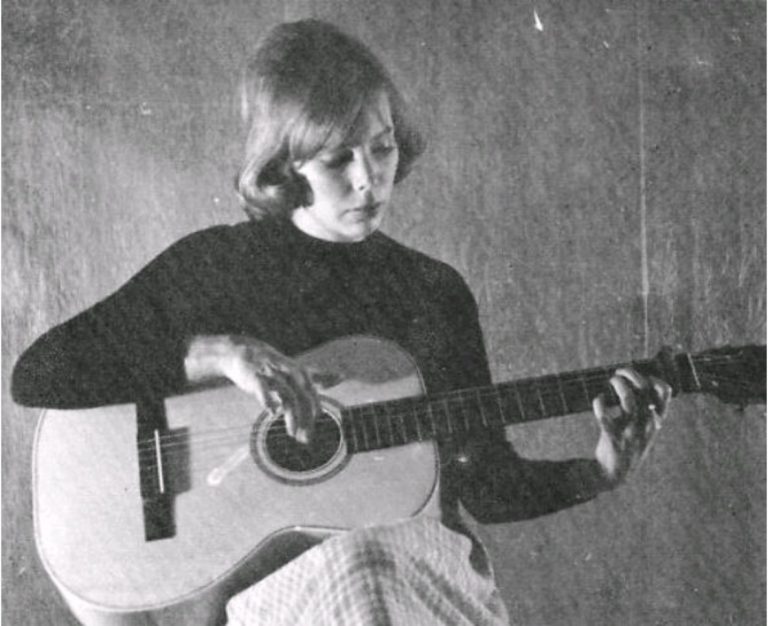

The second disc is fascinating as a snapshot of her own earliest songs, including the melancholy “Day After Day”, recorded on a Jac Holzman demo tape in August 1965, the first song she ever penned, written on the way to the Mariposa Folk Festival. A birthday tape she sent to her largely unimpressed mother Myrtle (an appraising spectre in some of Mitchell’s greatest later songs, including “Let the Wind Carry Me” from 1972’s For the Roses) includes the bewitching “Urge for Going”, the “first well-written song” of hers. There’s also “Born to Take the Highway”, one of the best of these ‘lost’ songs, which, on a later live rendition at Philadelphia’s Second Fret, she describes as “the only travel song I’ve ever written – before I travelled any place” – a fascinating statement for someone who went on to make perhaps the greatest travel record of all time, Hejira, in 1976. Already the chords and style are uniquely Joni, like a proto-“Cactus Tree”. Her left hand, weakened by a childhood bout of polio, led her to develop her own open tunings to make the guitar easier to play. From there originated a style that is truly underrated and consistently captivating.

By the time of the live performances gathered here from 1966, Mitchell had earned some stripes as a writer, with Tom Rush making “The Circle Game” already something of a standard. Songs like this, the gorgeous “Urge for Going” (a tale of the desperation of the harsh Canadian winters), and “Night in the City” immediately highlight her quick development in terms of melody and song structure. In the spring of 1967, she made various stops at the Philadelphia radio show Folklore, hosted by Gene Shay, and one performance includes a nascent, days-old version of “Both Sides Now”, assured from the first.

Early versions of songs that went on to feature on her studio albums begin to appear in her live sets and home demo recordings – “Conversation”, immortalised on 1970’s Ladies of the Canyon, is here with a different strumming pattern and alternate/additional lyrics; “Morning Morgantown”, also from Ladies, is faithful to the future recording; “Tin Angel”, from 1969’s Clouds, plays a little again with different rhythms. There’s a beautiful “Michael from Mountains”, later captured on 1968’s debut Song to a Seagull, from a June 1967 home demo with some lyrics from “Song to a Seagull” at the end. Perhaps most beautiful of all is the haunting tale of love gone wrong, “I Had a King”, where Mitchell’s melancholy, bereft lyric is matched by a melody that is dark, elegant, and serpentine. Hearing these early versions is a fascinating insight into this period of Mitchell’s career – particularly striking is that she is obviously still trying to find her own vocal style; the June 1967 home demo and her live performance of “Just Like Me”, for example, finds Mitchell playing with her voice, singing a little deeper, trying to uncover the right character for the song.

Similarly, her writing during this period can be uneven as she tries to find her own distinctive style. A song like “Favorite Color”, from an October 1965 Let’s Sing Out TV broadcast at the University of Manitoba, evokes the hinterland between the folk style of her earliest years and the strange, idiosyncratic, yet beautifully melodic writing that became her trademark. While the melody is reminiscent of the folk songs that were once the sum of her repertoire, her finger-picking style is becoming more evident.

But for every jewel like “Urge for Going”, “Born to Take the Highway”, and “I Had a King”, there may be offbeat experiments like “Dr Junk”, where the angular rhythms that seem to predate songs like “This Flight Tonight” don’t quite hit the mark, or the not-quite-formed “Cara’s Castle”. Then you get bizarre songs like “Brandy Eyes”, with its relentless charge up and down the scale, and “Gift of the Magi”, with its weird melodic leaps and unexpected chords, on the way to true beauties like “Come to the Sunshine,” a delicate and dreamy delight, and the mellifluous “Carnival in Kenora”. But throughout, Mitchell’s relentless growth and searching, her quest to push herself and come up with new ideas, is apparent; a fascinating curio is the snippet of “Joni improvising” on ‘Michael’s Birthday Tape’ in 1967, where out of the “mess” can come beauty.

By the time we arrive at Mitchell’s performance at Canterbury House in Ann Arbor, MI, in October 1967, the listener is now fully cognisant of the remarkable growth over the preceding four years. That earliest radio session in 1963 is a beauty; in the liner notes, Mitchell says folk music was “easy to imitate,” which definitely does down the loveliness of these performances. But there’s no doubt that, by the fourth and fifth discs, with Mitchell performing her own songs, she has announced herself as an artist, as a writer, as a composer to be reckoned with. Canterbury House may not be the best of her performances, but the strength of the writing cannot be faulted – included here is a freshly-written “Cactus Tree”, with a tuning intro where Mitchell wrestles with “a hostile G string,” and a husky, slightly melodically different “Little Green”, later recorded with a more nakedly vulnerable vocal performance on 1971’s Blue.

I have always loved my Joni best in the 70s, an era of true and often unparalleled artistic excellence. Perhaps because of her own dismissals, I didn’t think to take her earliest work as seriously – and while it is true that her later work is, as she describes, “smarter and richer,” this box set proves that, from the very beginning, Joni Mitchell had a command of her craft, a unique playing style, and the capability to push herself in unusual directions. It is a delight, and a pleasure, to hear this material for the first time and to better contextualise the beginnings of her remarkable, restless career. Joni Mitchell doesn’t start with Song to a Seagull – she starts here. It remains to be seen what treasures may emerge with further releases, but for now, let’s rejoice that there is still some new (old) material emerging from this singular, extraordinary artist.