“Though she is remembered for contributions to The Velvet Underground & Nico, her artistry and influence are often overlooked, whilst fellow Velvets Lou Reed and John Cale are hailed as icons.”

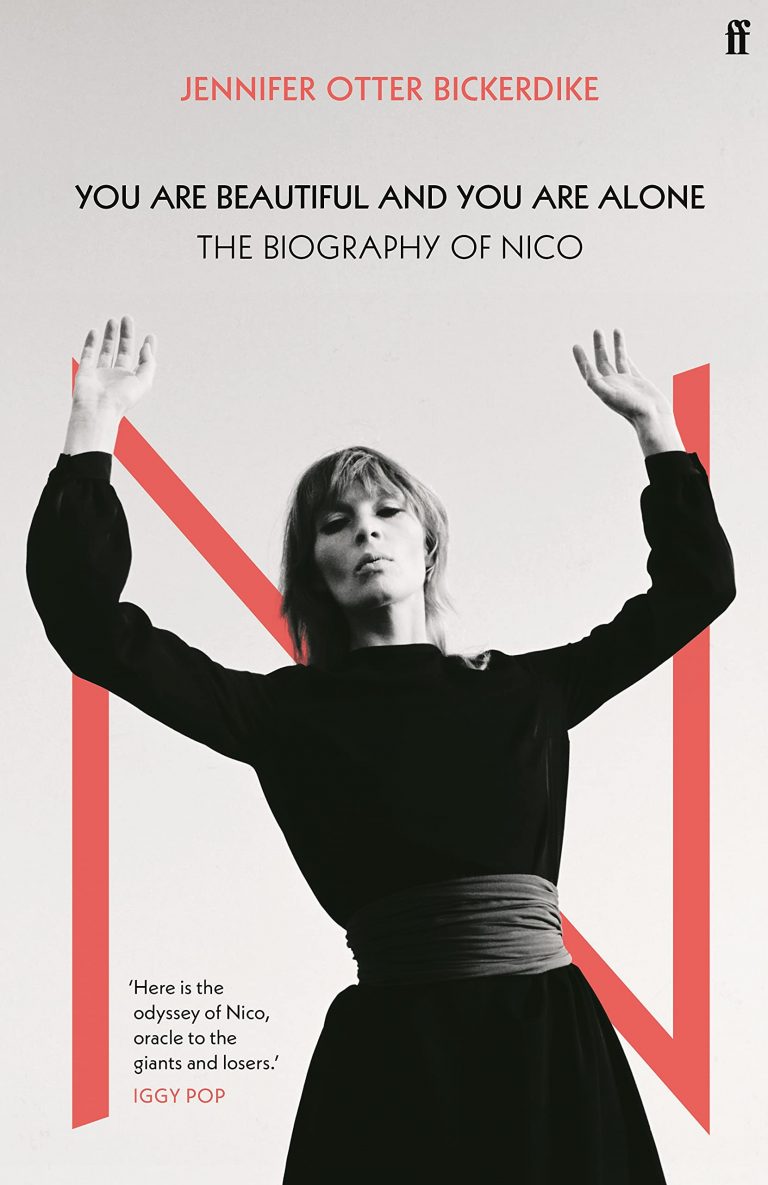

There is not a whole of literature about Nico, the extraordinary artist born Christa Paffgen in Cologne in 1938, that doesn’t focus on Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, or The Velvet Underground. Writer Jennifer Otter Bickerdike sets out to change that with her new biography, You Are Beautiful And You Are Alone, published this week by Faber & Faber.

Taking its cue from archival material as well as over a hundred new interviews with family, friends, colleagues, and admirers, it tracks the life of Nico from her childhood in WWII-ravaged Berlin through teenage trauma to her rise as a fashion model and film actress, Factory muse, and the strange, beautiful 20-year solo career she fashioned from the ashes of her Velvets experience. Otter Bickerdike seeks to “[defy] the sexist casting of Nico’s life as the tragedy of a beautiful woman losing her looks, youth and fame.”

Instead, the focus is on Nico’s tenacity – it is incredible how she continually managed to push through setbacks, rejection, and humiliation to keep going, keep positive – and resourcefulness; her willingness to put herself through the wringer to be taken seriously, the emotional turmoil surrounding the care of her young son and, ultimately, her incredible talent and creativity. Nico, much more than the ‘chanteuse’ that sang Lou Reed’s songs in The Velvet Underground and was ridiculed by members of the band for her German accent and hearing problems, became an artist and composer responsible for some of modern popular music’s most inventive and original works. The Marble Index, Desertshore, and The End, originally released between 1968-74, stand today as some of the most idiosyncratic records to emerge on major labels, with Nico at their centre on wheezing, ominous harmonium. She influenced a generation of artists, from Morrissey to Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bauhaus, and Björk.

Otter Bickerdike, from the off, wonderfully captures the essence of Nico’s childhood in a Germany ravaged by WWII through third-person testimonies from relatives (the voice of her Aunt Helma is particularly strong). The Christa Paffgen that emerges is shy, unusual, and determined: a young woman who parades in her finery at Berlin’s department store KaDeWe in the hope of getting noticed – and succeeds.

The narrative follows the teenage Christa through the mid-to-late 1950s as she earns a good living as a fashion model and drifts between European cities, New York, and Ibiza, adopting an enigmatic new moniker in the process.

But You Are Beautiful And You Are Alone makes plain the links between the itinerant Nico that drifted between cities, between scenes, and the difficult childhood of uncertain identity (Nico never knew her late father), of loneliness, and of rootlessness. The enigma that was ‘Nico’ was something of a shield for arguably an even more enigmatic Christa.

Reading about Nico’s days as a model and actress is fascinating – it was sometimes a case of ‘right place, right time’ (such as her appearance in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita), but Otter Bickerdike doesn’t shy away from exploring her near-misses and abject failures. The period during which she was trying to make it as a film star and, in the process, had a son with French actor Alain Delon makes for riveting, if unsettling, reading. Their son Ari’s early years in particular are depicted as sad and difficult, the young boy caught between families, destinations, and Delon’s persistent denials of paternity.

Otter Bickerdike of course delves into the years with The Velvet Underground and Andy Warhol and vividly captures the mood of 60s New York and, subsequently, the influence and impact of artists like Jim Morrison on Nico. Morrison and Leonard Cohen are presented as encouraging forces, bringing out the latent poet and writer in Nico.

One of the most glorious of the new interviewees is Iggy Pop, who speaks of Nico with a refreshing degree of respect and understanding. “I’m absolutely convinced,” he says, “that someday, when people have ears to hear her, in the same way [they] have eyes to see a Van Gogh now, that people are gonna just go ‘WHOOOAAA!’.” Iggy, of course, appears in the superb film clip for Nico’s “Evening of Light”, filmed in 1969. The Wicker Man on heroin it most certainly seems to be.

Much of Nico’s life was, and still is, shrouded in mystery. The oft-repeated story that she was exiled from America in the 1970s due to a racially-motivated attack on a young woman is explored here. Otter Bickerdike gathers sources and, while the story isn’t ‘ironed out’, finally some different voices have a chance to be heard. Likewise, it is revealed that Nico’s son Ari, contrary to rock apocrypha, was introduced to heroin by an unnamed male acquaintance – not, as is often reported, his mother. (Although it is made clear that Nico and Ari, upon their reunion in his late teens, did partake together.)

Nico’s ‘wilderness years’ of the 1970s, where she spent time doing occasional gigs and making films with Philippe Garrel (when they were not doing heroin in their grubby black-painted Paris apartment), remain a little murky, but the reminiscences of German artist Lutz Ulbrich shed some light on this strange period.

The book really hits gold though as it recounts Nico’s life in the 1980s as a heroin-addicted artist constantly on the road, performing her music in often bizarre situations in clubs to fund her habit. But, a little unlike James Young’s brilliant memoir Songs They Never Play on the Radio, here you really get a sense of the spirit of community and camaraderie that Nico found while living in Manchester in the 80s. The interviews with Barbara Wilkin and Jane Goldstraw are beautiful and cast Nico in somewhat of a different light. There are also joyful revelations like her crush on Rip Rig + Panic’s Sean Oliver, her predilection for lunchtime pints and games of snooker, and her love of The Times crossword. There’s also some more detail on the mystery surrounding the production of her highly underrated 1981 LP Drama of Exile, a record that was tracked twice during a period in which Nico’s ‘manager’ also happened to be her drug dealer.

Otter Bickerdike also incorporates text from Nico’s personal diaries. It is illuminating to hear Nico’s ‘voice’, as it were, particularly around the time she managed to kick heroin in 1986 and was replacing it with methadone. The Nico of 1988 has a much more positive outlook, and friends and colleagues remark on the change in her behaviour and attitude – which makes her lonely death from a brain haemorrhage on the island of Ibiza in July 1988, aged 49, all the more painful.

You Are Beautiful And You Are Alone, then, is a welcome addition to the smallish canon of Nico books, particularly for its insight, empathy, and, crucially, its respect for the subject as an artist and creator. Otter Bickerdike successfully weaves archival material together with new interviews to create a new and intriguing portrait of a singular artist. Recommended.