The concept album has always presented a fair amount of ambiguity. Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours may well have captured a tone, but the idea of a ‘storyline’ has long been hefted, or ignored, by convenience. Hip hop, in particular, has long been uncertain how to tackle the beast. It was perhaps best addressed in 1999 with Prince Paul’s A Prince Among Thieves, and the likes of Masta Ace have come close more recently, but the concept album remains an often feared challenge for MCs. It makes sense: between the pastiche of tracks, the inherent variety of a hip hop album makes true consistency, or a narrative, difficult. Simultaneously, it’s deeply ironic, coming from an art form so steeped in storytelling. The Roots are no strangers to what could be considered a concept record, but Undun is nonetheless new territory.

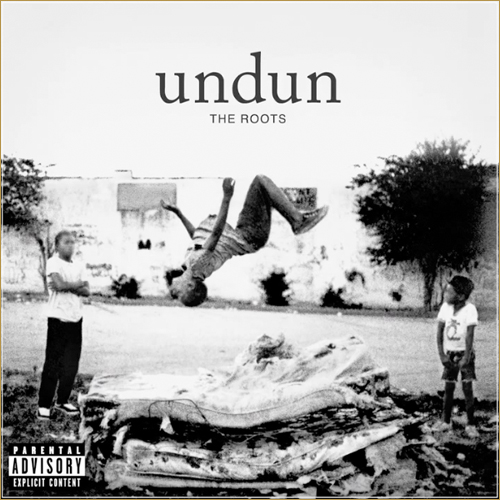

From the start of the flatline that serves as the album’s opener, this is the life and death of one Redford Stephens, one part entirely a fictional creation, the other memories of friend’s passed. Regardless, he is the manifestation of the unknown, the figures that make up saddening, but faceless, murder statistics. He is the Black Youth, misled. The album’s tale moves back from that flatline – Stephen’s murder – moving back through his life and times.

It’s both a daring move and where the album grows somewhat murky. It’s the inevitable challenge: how much story can you get across through the speakers? The usual Roots guest roster, along with the likes of Big K.R.I.T., appear as various characters, but its often anybody’s guess as to who. Ultimately, it doesn’t much matter. It’s the broader story through which Undun gains its strength; through the musings and rants of Black Thought and Dice Raw (who, this time around, has near as large a presence as the group’s leader).

The certainty of the opener gives the listener context, but for most of the record, it’s less about the story, but rather, its voice. Understanding it as the tale of a lost youth is all one truly need understand. After all, does life proceed as a perfectly styled storybook, or a series of images? It’s these that each track creates. Redford is a device to explore crime and punishment, more than a breathing character. His purpose is to consider the effects of the ghetto on a young mind, and vice versa. The tone is relatively consistent, harsh dialogues peppered over to the point production on cuts such as “Tip the Scale” and “Lighthouse.” Both are triumphs, The Roots combining their ear for music with strong penmanship as much as they ever have.

However, it’s in the album’s last four tracks that the greatest intrigue arises. Simple instrumental pieces, they have received a range of interpretations, but this writer got something concrete from them. Seeing as the album begins with Redford’s death, they can only be seen as his youth, his birth. The tracks are earnest and, aside from “Will to Power,” sweet. For Redford, and more importantly for The Roots, this was life prior to the ghetto. Its an interesting conceit, to dismiss the focus of the album for its closing. Yet doing so only puts the album’s earlier, harsher, material in greater focus. Given too much scrutiny, the tracks could be seen as Redford’s mind prior to rap taking hold. Perhaps ?uestlove and folks are making some deep ‘love you, hate you’ gesture to their art form, but a simpler conclusion seems more likely.

These pretty little ditties were Redford before he gave in to the world around him, before he could understand it. It’d be a prettier story if the kid was a prodigy, but the man The Roots present is no hero, no champion. It’s an album grounded in dying about life. The tone is hence of course intentionally muddled, hopeful one moment, grim the next. There lies the greater, harsher, truth of Undun. No criminal is simply a criminal, and Redford hopes and dreams, but he is ultimately deluded. “A lot of niggas go to prison, how many come out Malcolm X?,” Dice wonders aloud. For every Curtis Jackson, there’s dozens of teenagers who never made it to their first mixtape, and many more who never even considered a way out, before bleeding out on the street. As the life leaves our protagonist in the opening moments, he is certainly one of them. So long as we’re listening, for a brief moment, we get some sort of insight into this, regardless of color or creed. If that isn’t what the greatest hip hop is meant to do, what is?