The thing about visiting Hawaii and other islands stranded in the ocean is, after a while, you begin to feel like you’re stranded in the ocean.

Granted, our capacity for withstanding anxieties enforced by distance was greatly enhanced during the pandemic. Yet, while Unknown Mortal Orchestra’s Ruban Nielson already split time between Hawaii and New Zealand and recorded the band’s latest set with his brother and father while living in a Hawaiian commune of sorts with other family, he still ended up writing an album that was inspired by a youth spent traveling and freely moving.

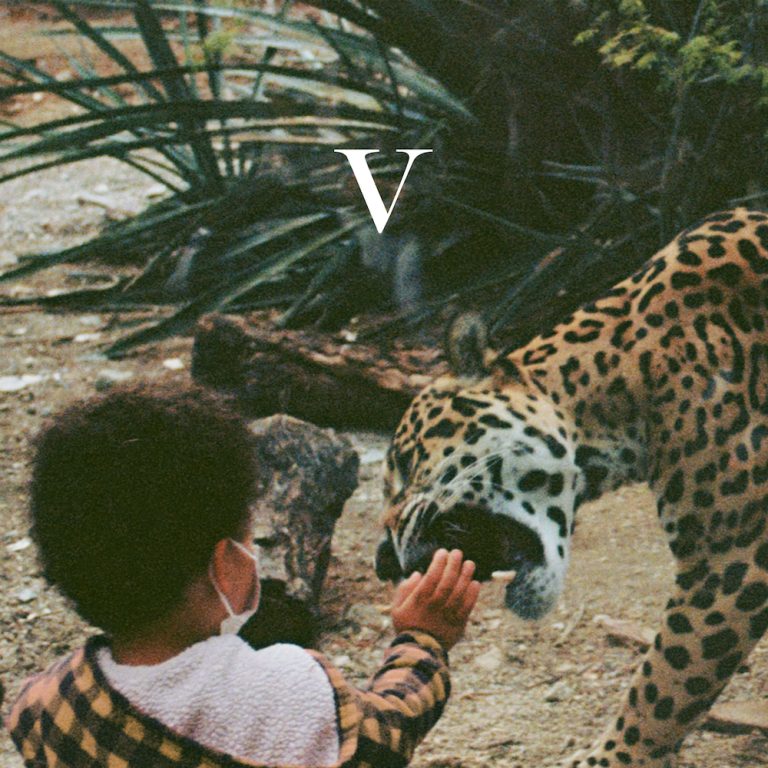

Another aspect of island life that infects V, UMO’s fifth album, is ‘It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere’. Not only did three singles trickle during an 18-month advance from an artist who’d previously churned four albums out in seven years, but V’s chief characteristic is its urgency – or lack thereof. Despite the ill ease, it’s loose. Jammy. Off the cuff. Pouring its fourth cocktail. Nielson’s voice – a Sly Stone/Bon Iver lovechild that at times recalls Prince’s Camille alter ego – has never felt more confident.

Perfunctorily dubbed a “double” album by Jagjaguwar, it only halfheartedly approaches that novelty. If V betrays decadence, it doesn’t manifest itself as sprawl or poor editing – much less a notional narrative. Its languidness is actually its charm, a direct contrast to almost anything in UMO’s fidgety catalog save “Jello And Juggernauts” from the 2011 debut.

It begins ominously, and its restive fire is never fully quenched. “The Garden” carries with it all manner of Eden connotations. Shrouded in UMO’s familiar compression, Nielson warns “Hold on tight / It’s violent after dark / in the garden.” Suspended open notes create a suspicious tension that finds little resolution in an angsty, bluesy guitar solo that skips through phrases in vain hope of landing on a repeatable melody.

“Guilty Pleasures” latches on to this feeling: a distorted, electronic drumbeat is joined by what sounds like a distorted, electronic piano while Nielson’s vocal slips at its own meter from ledge to ledge. He reminisces about a 17-and-a-half-year-old serial masturbator who can’t wait for temperatures to rise so more clothes can come off. Later, poor “Nadja” successfully staves off his advances.

Idleness and idle thoughts recur as themes. “That Life” mulls inebriation as a salve for boredom, trying to hold onto a buzz into sunset because there’s nothing else to do when you’re burnt to a crisp. Among the several instrumentals, “Drag” spends six minutes circling, like a feather dropped from an airplane. Nielson impatiently ticks off the days of the week during “Weekend Run”, musically a sly nod to The Bee Gees and Saturday Night Fever. Elsewhere, the similarity in the melodies of “Meshuggah” and “Layla” can’t be obscured by their opposing rhythmic schemes (Boz Scaggs vs. Big Mountain), suggesting that, while Nielson’s imagination runs wild, the ideas are all springing from one spot.

A 19th-century anthology of Hawaiian witticisms and proverbs included an ironic statement that translates to “Everything is pleasant and smooth.” Though the sentiment would also complement their great love of bald jokes at the time, it says that even the ancients shared some of Nielson’s predicament: the incumbency of having to enjoy all this useless beauty when you’d rather be someplace else.