We are so back.

After two decades of often deeply flawed releases, there’s a Smashing Pumpkins album I feel wholly comfortable to give a seal of recommendation to! Aghori Mhori Mei is Billy Corgan’s return to his true passion, a fully formed and cohesive work that sounds like an actual Smashing Pumpkins album without resorting to self-references.

For the longest time, that seemed impossible, as there was a marked divergence in Corgan’s work after the band’s breakup in 2000. Following his undervalued tenure with alt-rock supergroup Zwan and the often ignored but visionary cyberpunk-shoegaze masterpiece The Future Embrace, Corgan fought through a decade of strangely self-sabotaged releases. The really good Zeitgeist featured great songs but suffered from a rushed, botched production job. Teargarden by Kaleidoscope was left unfinished, while Chicago Kid and Day for Night were shelved. Oceania was a welcome return to the familiar Siamese Dream formula, but had synths as bland as its random cover artwork, while Monuments to an Elegy just felt underdeveloped and insignificant. What had happened?

There’s a few reasons. For one, it’s that the Pumpkins always had a coherent sonic vision. At the heart of their early works was a psychedelic understanding of sonic textures, married to Billy Corgan’s unique and intimate vocal delivery. This opened the door to their uniquely gothic variant of shoegaze (“In my Body”, “Porcelina of the Vast Oceans”, “Behold! The Nightmare”) to exist next to weed-fuelled epics (“Mayonnaise”, “Starla”, “Drown”). It allowed atmospheric ballads that could shift in tone from vaudeville (“Lily”) to country (“To Sheila”) and invited in new wave (“Here’s to the Atom Bomb”, “1979”) or industrial (“Eye”, “Whyte Spider”). Guitar melodies often carried Corgan’s complex ideas forward, and synthesisers communicated an ominous, icy cyberpunk tone.

While there’s a ton of amazing songs on the 2.0 releases (“United States”, “Inkless”, “A Stitch in Time”, “Stellar”, “Panopticon”, “Tom Tom”), as albums these works struggled to unite elements the Pumpkins used to merge effortlessly. Everything sounded like a struggle, some of what was once intimate or expansive just felt a little drab or generic, leaving works that were good but never truly great. The return of James Iha and Jimmy Chamberlin brought more focus, but also a lack of editorial vision. Shiny and oh so Bright had the clueless Rubin touch, CYR was a breath of fresh air but overlong and ATUM marked an album so bad it often felt like self-parody, doing disservice to the few enjoyable songs buried occasionally.

So maybe Aghori Mhori Mei can be read as a creative fire ritual, an attempt to shed the toxic influences that had befallen prior albums. Billy Corgan has talked extensively about wanting to reconnect with the spirit that allowed him to create his most beloved albums, a “dark” and “dangerous” mindset, which made him feel insecure again. That’s also the key to the album’s cryptic title. The Aghori are a Hindu extremist sect that reject societal norms and indulge in dark rites of cannibalism and death worship. Mhori likely is an alteration of Mahori (derived from the Sanskrit term for beautiful or attractive), which refers to a Thai musical string group, while Mei is a Hindi possessive, used as in “my coat” or “my band” – which also connects with Corgan’s familiar play of reconfiguring his band’s image with each project.

But things are far from the macabre on AMM. Here, the Pumpkins indulge in rich, punchy stoner rock, unearthing a couple of genuinely memorable mid-tempo singles and switching up textures without losing their touch – and it’s refreshing to hear the group in such good spirits and fully confident of their abilities.

The ominous, searing grunge opener “Edin” is a viciously effective tone-setter: Iha and Corgan duel in this Black Sabbath-soaked rocker, which occasionally allows for psychedelic guitar nuances a la “Hummer”, while Jimmy Chamberlin finally challenges himself again. Where he seemed to play on a click-track for most of ATUM, here he lets loose with the full skill of the virtuoso he is. It’s a thrilling track, the kind of thing you’d expect to learn was cut from Dirt or Superunknown, a song that leaves audiences in ecstasy and immediately erases any doubt that the band still got it.

“Pentagrams” is on the more progressive side, with an opening echoing that of Pink Floyd’s “Hey You”, a structure that dives in and out of synth-interludes and almost Depeche Mode-sized pathos in its chorus. The track feels like an elaboration on “In Lieu of Failure”, in a way providing a lone link to the experiments of ATUM, but with an intentionally more complex composition in place. It also connects with the album’s other overtly prog tracks, the moody “999”, which uses Piano interludes to suggest a gothic sense of forlorn sadness. With its maelstrom-like guitars, it sounds like a sibling to Superheaven’s TikTok standout “Youngest Daughter”. Considering the resurgence in post-grunge in Zoomer culture, it’s easy to imagine this becoming a fan favourite.

The heavy tracks really manage to shine throughout AMM, at times reconnecting with the raw energy present on Nirvana’s Bleach more so than with the pastel romanticism of early Pumpkins. “Sicarus” has that grim 1989 tone that desperately fought to set itself apart from the hair metal groups that dominated the airwaves and charts, with a stone cold, unforgiving metal riff and punchy chorus that finally opens up the stage for a bridge that has Chamberlin blast away. “War Dreams of Itself” speeds up the tempo, chugging and screeching away, before it settles on a brief interlude. Pleasant and punchy, it’s still one of the somewhat lesser tracks here – yet it’s elevated by incredible guitar mastery and sheer attitude. “Sighommi” is a better, more uptempo cut, all chromatic in its Deftones-like power and infused with James Iha’s beautiful and intuitive playing as well as (if my ears don’t betray me) Katie Cole’s tasteful background vocals. It’s pure euphoria, wisely cutting out before the song reaches the three minute mark, a total banger and an easy pick for lead single among the heavy rockers.

Yet there’s a song that outclasses it and is likely destined to be universally regarded as AMM‘s standout: “Goeth the Fall” is a mindblowingly good mid-tempo track. Marrying the tone of late 90s Manic Street Preachers and Foo Fighters (that brief moment when both groups managed to distill their individual genius into mainstream compositions without seeming hokey), it’s an autumnal quasi-ballad whose melody is written as an inversion of “1979”. Its majestic chorus, with a particularly wistful guitar melody, and beautiful piano bridge are among the best Corgan has ever put on tape, echoing Machina 2‘s best ballads (“Home”, “Here’s to the Atom Bomb”, “In my Body”) but feeling like a novelty within the band’s catalogue. Shiny… had tracks that attempted a similar tone – “With Sympathy” and “Travels” come to mind – but they didn’t manage to be as emotive or fully formed as “Goeth the Fall”. It possibly outdoes “Neverlost” and “Pale Horse” as more significant and successful within the canon of 21st century Pumpkins ballads, and I can’t stress enough how incredible it felt to listen to it for the first time.

Speaking of “Pale Horse” (which is quite underrated in the band’s catalogue): “Pentecost” feels like a modern reconfiguration of the particular, orchestral writing that’s also inherent to “Disarm”. Starting with only synths, it allows Chamberlin to come up with some incredible drum textures, as one by one, the orchestral backing grows to a rousing climax. It’s not so much synthetic as it is a better representation of the cosmic operatic vision Corgan had for ATUM – had that record indulged more in the atmosphere and tone of “Pentecost”, it could have been an incredible success. It also feels reminiscent of David Bowie’s comeback track “Where Are We Now?” in its open-ended, questioning aura, and it would be interesting to figure out where Corgan sees this particular sonic direction heading in the future.

The weakest of the quieter tracks comes in the strangely over-written “Who Goes There”. It’s a nice track with a pretty melody, but Corgan switches octaves too quickly, transposing the individual elements to the point where it seems a little over-emphasising. It’s likely the track would have worked better if Corgan had just recorded it as a demo-like, quiet track in the tone of “To Forgive”, “Stumbeline” or – hell – even “Galapogos”. Somehow, with those octave switches and full band backing, it feels like the album’s most exhausting song, even with it clocking in below the 3:30 mark. It’s not disastrous, just a missed opportunity to trust a more minimalist, naturalist, unvarnished approach.

Yet, to be honest, if there’s a criticism that should be levelled at AMM, it can be found within its sonic structures. And with that – with my full heart – I will say:

please, Billy…

Let go of Howard Willing.

Willing has been with the Pumpkins for a long time now, and most prominently worked with and produced Corgan’s last couple of albums. And they all suffer from baffling sonic choices. When a song would benefit from a raw, live room recording, Willing seems to be insistent to go for digital fragmentation. When Corgan’s voice should have some natural delay of a specific space (maybe recorded in a broom closet or bathroom for a change), Willing dries it up or modulates it unfavourably, adding tinny treble – and often pushes it to the foreground. Echo or delay, when it occurs, is also often noticeably digital, just as synthesisers often feel unnecessarily accentuated over more charismatic guitar tones.

On AMM, the band sound is better than on many of their recent rock tracks, but there’s a lot of bewildering sonic choices that keep this record from reaching the strata of brilliant Smashing Pumpkins masterworks. Just listen to how odd Corgan’s dry lead vocal lines sound on “Pentecost” in direct contrast to the reverb heavy instrumentation, or how the overtly clean studio sound of “Who Goes There” erases the recorded intimacy that made “In the Arms of Sleep” such a standout on Mellon Collie… As I said in my review of ATUM, it’s bewildering how a producer can make so drastically different sonic approaches sound so incredibly indistinguishable and bland, without any divergence in recording technique or studio-specific creativity in how to best use a room’s dynamics.

So please, Billy, call up BJ Burton – he’s worked with Low and Soccer Mommy and even with Miley Cyrus. He knows unique ways of distortion, capturing an aura that reconfigures atmosphere like a sonic alchemist. You’re touring with Interpol, see if they have Peter Katis’ contact: his ability of reproducing a nocturnal, cavernous density that feels both enormous and claustrophobic has rocketed multiple post-punk bands to superstardom, likely the closest to Flood’s style of any millennial producer. Or just try and see if Dave Sitek would be up to experiment – he’s created unique environments for and collaborated with musicians as versatile as Scarlett Johansson, Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Liam Gallagher’s Beady Eye, I’m sure he could bring out a totally unique shade of the Pumpkins we have yet to hear.

As somebody who just attended the spectacular “The World is a Vampire”-tour – which many agree marks one of the Pumpkins’ best live experiences – I can attest that even the weakest recent tracks sound absolutely spectacular when heard in a live setting, all natural room sound and emotive band dynamics. And to think what any of the three producers I just came up with there could add to the band’s sound… the opportunities seem mindblowing!

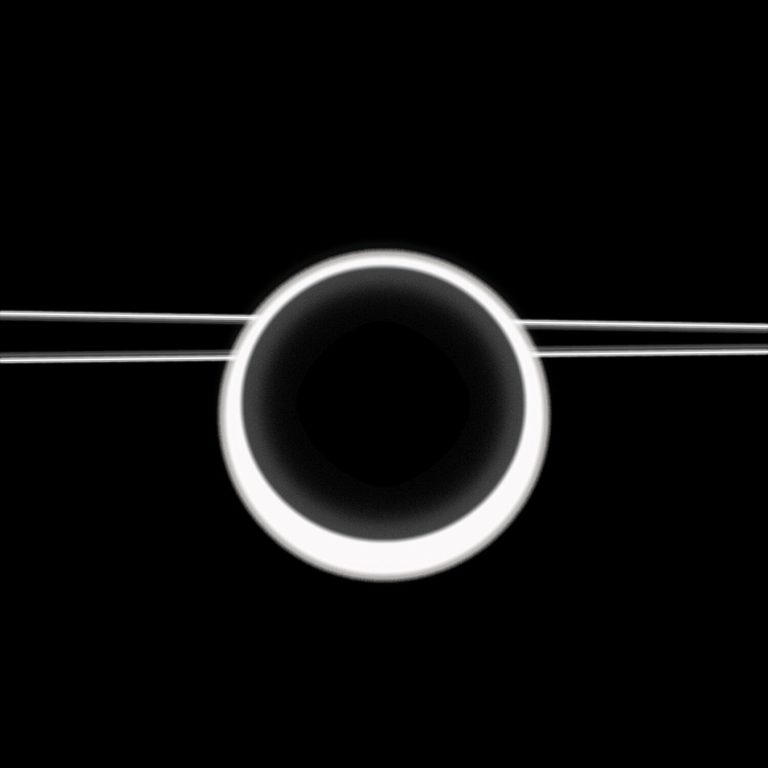

Still, I don’t want to sound too negative about this record. Closing with the powerful, baroque orchestral ballad “Murnau”, Aghori Mhori Mei is a throughly tasteful, poignant and rewarding album. Here, in its last moments, it summons the spirit of silent cinema, of gold plated curtains and haunted cinema screens. Murnau’s skull was – famously – stolen from his grave a few years ago. Why remains a mystery. There’s surely a part in Corgan who muses about the strange twist of fate here, as Murnau died in a car crash when he seemed at his most powerful – an echo of loss that extends itself through pop culture, taking from us Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain, Heath Ledger. The theft of his skull seems as much connected to a secret, occult mythology within silent cinema’s DNA (Murnau’s Nosferatu remains as otherworldly and menacingly organic as it must have felt a century ago), as it is symbolic of the extremes iconographic adoration leads to. So of course, “Murnau” had to end up one of Corgan’s most longing and mournful songs – a finale that, would this mark Corgan’s last statement, would seem painfully fitting.

But let’s hope that’s not the case. The Smashing Pumpkins are back. Here’s to masterpieces yet to come! It feels so strange, and alien to say this, but this is the band I fell in love with, almost 30 years ago now. A band I had thought lost to time. Passionate, sensitive, melancholic, aggressive, libidinal, eternal.