The real beauty of life is its impermanence. It takes a while to work this out, but it’s true. Nothing is forever, and things can’t (and shouldn’t) stay the same, no matter how hard we try to rally against uncertainty and change. Some elements radiate with longevity while others slip by like tears in the rain if we’re fortunate enough to be able to learn to let them go.

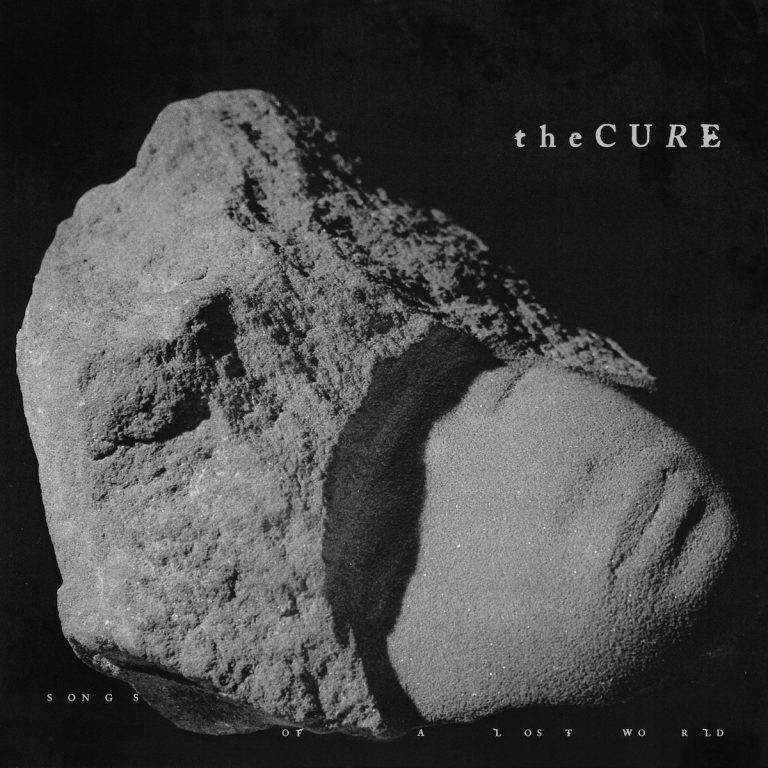

The one absolute certainty of life is its ending, and The Cure‘s Songs of a Lost World is about exactly this – mortality and the passing of time. It’s an astonishing record, with Robert Smith nestling deep within the subject matter where he most excels, exposing layers of vulnerability like never before. There are (thankfully) no attempts at radio friendly songs here, but there are plenty of hooks, melodies and lyrics that stay with you long after the album’s over. Condensing the record to a single phrase is best left to its creator, and Smith sums it up perfectly on the opening line of “Warsong” where he declares “Ah, it’s misery”. It’s life-affirming misery, though.

We all know it’s been a long time between these eight songs seeing the light of day and the band’s last album, the middling 4:13 Dream. Sixteen years and five days to be exact, but who’s been counting? That record was rightly no better received commercially or critically than the few that preceded it, and The Cure looked destined to agonisingly transmogrify into a heritage band that would tour now and again to a hardcore fan base and BBC 6 Music centrist dads who would pop along out of a nostalgia for something they’d never really lived or loved the first time around and would just want “the hits”.

Thankfully, we finally have this record which is up there with their best. I’ll die on the hill arguing that here’s no such thing as a bad Cure album, but for many (this jaded hack included) the band’s creative heights dwell in the darker recesses of their work – the bleak Faith, the even bleaker Pornography, and the sumptuous melancholy of Disintegration. Gratifyingly, Songs of a Lost World dials up the bleak to 11. None more bleak.

Album opener “Alone” is simply stunning on every level. You’ve likely heard it by now – glacial, regal, emotive. You’ll need to check for signs of life if you didn’t feel a twinge of humanity when you first heard Smith opine “This is the end of every song that we sing”. It’s about the cessation of life, friendships, impending climate catastrophe, time. It’s about big ideas while remaining resolutely intimate and personal. Simon Gallup’s guttural bass is exquisite, while Roger O’Donnell’s serene keyboards wash over proceedings in a pensive, funereal manner. The theme of ageing and slowing down is not new for Robert Smith – he’s been writing about such things since he was in his 20s – but it’s more painful to listen to now. There’s a sense of raw, vulnerable honesty here replacing the existential angst of yesteryear. An instant classic, for sure.

A more serene feel comes with “And Nothing is Forever”, which follows the same structural template as “Alone” with a gorgeous intro that’s in no rush to move aside – an idea commonplace on the record as a whole. The lyric of “Promise you’ll be with me in the end” shows Smith in a light he admirably and rarely shies away from – an infantilised sense of helplessness that entwines pure love with total need. The sense of self wrapped in the existence of another is central to innumerable songs that Robert Smith has written; a focus on the outcome of the Lacanian mirror stage where the ego is shaped for some to be absolutely dependent on others (a parent, a lover, external forces) in order to feel any sense of fulfilment. The repetition on this song of the phrase “However far away”, with its obvious association with Disintegration’s “Lovesong”, is a key moment for the album, and one which leaves a trail across the record that you pay more heed to with each listen. This is Smith looking back, sometimes in a self-flagellating manner as he focuses on missed opportunities and wasted time, and elsewhere (and perhaps quite subconsciously) a subtle celebration of his own work. It’s intertextual, self-referential homage. A form of acceptance.

One of the wonders of the record is how Smith has managed to preserve the exact same singing voice for years now, and this is nowhere more evident than on “A Fragile Thing”. Other godhead luminaries that could be considered Smith’s peers – Scott Walker, David Sylvian, David Bowie – all changed their vocal styles as they aged, but Smith seems to be locked in some weird Dorian Gray style pact that’s kept his vocal cords in check since about 1982. There’s an answerphone message of his voice locked away in an attic somewhere that’s constantly decaying. “A Fragile Thing” is a shimmering song, with a juxtaposition between the sprightly arrangement and the subject matter with intertwining piano lines to the fore.

“Warsong” is about deteriorating relationships, and can be read on a micro or macro scale. For those who really feel the world is lost, this song will be interpreted as a treatise on genocide, political poison and the current sleepwalking into fascism that surrounds us. For others with a little more hope in humanity, it can be read as being concerned with the inevitable failings of interpersonal dynamics. It’s a suffocating song, with O’Donnell’s incessant minimalist keys (think “Untitled” or “Harold and Joe”) smothering the track in warm textures while guitars meander above, directionless.

“Drone: NoDrone” is the ‘catchiest’ song on the record, albeit one that has its earworm element well hidden behind a wall of noise and wailing guitars. Reeves Gabrels’ solo is beautifully disjointed; resistant to embedding a refrain on a record that takes great pleasure in elongated repeated patterns. Jason Cooper’s drum sound is raw and muscular, underpinning everything with meticulous care. These two songs sit well next to each other on the record and share the same issue – they could have been longer.

There’s always existed a sense that Smith just wants to be held, even for just one last time, to be reassured by the words and presence of another. This sense of helplessness pervades the record, nowhere more starkly than on “I Can Never Say Goodbye”, which is lyrically as heart-on-sleeve autobiographical as Smith has ever been on record. There’s always been a sense that he’s a writer of personal truths, but these are often obfuscated by extended metaphors that lean on dadaist nonsense, or ‘cut-up’ statements that form an albeit fragmented whole over time. “I Can Never Say Goodbye” is about Smith’s older brother dying of cancer. His voice breaks when he delivers the lines, and there’s a naïveté to the lyrics that hits hard if you’ve ever felt this level of loss, or at least had it come frighteningly close. In moments of trauma we lose the ability to be poetic. Throughout his career, Smith has been the totem for isolationist angst, playing with being unguarded whilst using lyrical form as a barrier to real exposure. Here, he’s just plain vulnerable.

Again, Smith is something of the child here – in awe at the world in places, tearing his heart out because of its seeming injustices elsewhere. You’re reminded that he once wrote the overtly stoic lines “The world is neither fair nor unfair / It’s just a way for us to understand” on “Where the Birds Always Sing” some 24 years ago, whereas now he’s railing against those things you can never have influence over, with words left unsaid, and goodbyes never being allowed to take place. It’s testament to Smith’s ability to allow himself to be seen in such a way, and it’s done in a manner which never feels exploitative or over played.

The shallowest of glances at The Cure’s back catalogue makes it clear that this is a man who has always known how precious and precarious life is, how important the smallest moments are in defining what makes us human, and how the gnawing presence of mortality is usually impossible to ignore. From the nihilistic and impersonal statement of “It doesn’t matter if we all die” on “One Hundred Years” to this, Smith has centred much of his work on goodbyes, on being left alone in distress, and on death itself.

It’ll be difficult for hardcore Cure fans (and they are legion) to not find connections across the eight tracks of Songs of a Lost World with earlier output from the band’s songbook, whether it’s the plea to wake up of “I Can Never Say Goodbye”, which mirrors deep cut b-side “Chain of Flowers”, or the foley sound atmospherics that introduce the song and harkens back to Disintegration’s best track “The Same Deep Water As You”, but these are all touching points rather than the signs of an artist simply recycling.

Without doubt, this is the most exquisitely produced Cure record – layered instrumentation, vocal inflections and breaths are hidden deep within the mix with something new grabbing your attention on every listen in a way that unexpectedly enhances the sonic palette of the band. Production duties were handled by Smith with Paul Corkett who previously worked with the band as co-producer on the wonderful but often overlooked Bloodflowers back in 2000, an album that has much in common with Songs of a Lost World both in terms of overall aesthetic and lyrical motifs. Even on the languidly paced songs, there’s a vibrancy in the record’s texture which is impressive and highlights Smith’s desire to always move into new ground.

The opening to “All I Ever Am” has echoes of Loveless-era My Bloody Valentine; it’s equal measures graceful and woozy. The song is an outlier on the record overall as it’s centred on an ascending chord sequence compared to the more dour songs it sits alongside. It shares similar narrative themes with the rest of Songs of a Lost World in terms of looking back with some degree of regret about choices made, subsequent consequences, and somehow never feeling enough. There’s a skittish mood here musically, and feels more mildly downhearted than the wallowing pessimism that encases the record as a whole. It’s something of a widescreen song on an album that would be shot in 4:3 aspect ratio if it were a film. It’s merely respite before another wall of misery is unleashed.

Robert Smith has always had a knack of writing absolute killer closing tracks. “Endsong” just might be the best of the lot. We’re in familiar territory from the start with a long, winding intro that allows small shifts in arrangement so that each musician can be heard. Gabrels comes into his own with a sprawling guitar sound that feels wayward but always in control. Hard to believe he’s been with the band for over a decade and this is the first recording he’s been involved in (I’m obviously discounting the 1997 single “Wrong Number” because it’s rubbish and some things are best left ignored).

“I’m outside in the dark / Wondering how I got so old / It’s all gone, it’s all gone” essentially summarises the whole feeling of the record, and as the vocals come in the instruments sit back knowing where our attention needs to be. Cooper’s sparse drums and some keyboard washes are all that’s left, Smith once again exposed and open. It’s a wonderful closing statement, and really isn’t for the fainthearted or easily bored. Once the first part of the lyrics are done the band come back in to create a cacophony of beautiful noise as Smith’s words become more of a holler, more intense and exhausted as the end comes. It’s imposing, ominous, and enthralling in equal measure. Songs of a Lost World might just be a masterpiece. It takes more than three weeks of constant listening to a record to make such a clickbait-laden, headline grabbing claim hold up to genuine scrutiny, but it’s as close to perfection as any of us could have hoped for.