While the cultural discourse remains ever too preoccupied trying to crystallize the moment, the tireless Shabaka Hutchings stresses constant movement. Such is the fate of a trailblazer: always elusive, always surging forward with incisive fortitude and pace. Just when we think we’ve caught up, we are still unable to comprehend the new ground broken until maybe decades later. Some artists have even transcended further than one can ever hope to understand: the great Sun Ra comes to mind.

Suffice it to say, Hutchings hasn’t looked back much either to linger on what we make of his considerable output thus far. In outfits like The Comet Is Coming and Shabaka and the Ancestors, his signature gatling-gun sax pounce burrows its way deep into our core, seeking untapped human realities: one flirting with dystopian, futuristic imagery, the other unearthing the fluent lost cosmologies of the past.

In a trite, feeble attempt to classify the unclassifiable, let’s just frame Sons Of Kemet – the other high-profile Shabaka-led ensemble – as one big, stretched-out musical mantra that treads the urgent now like a constantly flowing river. The group’s previous LP Your Queen Is A Reptile wasn’t just a record of reverence that enshrined historic Black women’s voices (namely Albertina Sisulu and Yaa Asantewaa), it was both incendiary and delightfully naive in carving out its own sonic path, irreverent towards jazz music’s well-documented mythologies and doubling further down on Shabaka’s own musical heritage, which is rooted in the propulsive Caribbean music of Barbados – the place of his own lineage.

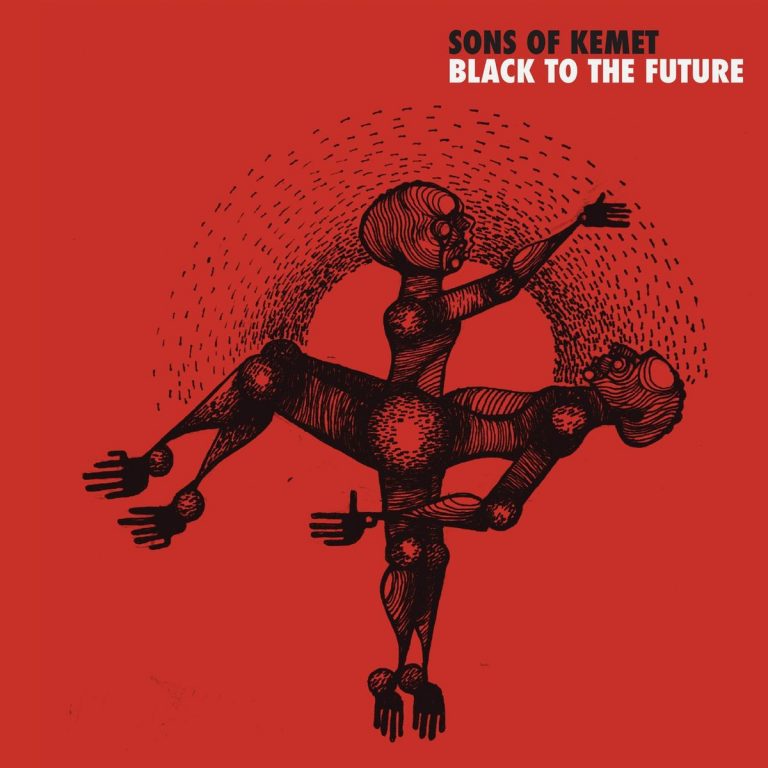

In other words, it’s all about constant movement. Sons Of Kemet’s new album Black To The Future is rife with this constant movement. Consider the title’s little nod to the film franchise more of a reclamation. Because, like most other things in popular culture, science fiction is an inherently Black invention. Even the act of improvisational music of any kind could be considered science fiction transmuted into music: summoning new actualities through sound. Recorded in the wake of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police, Black To The Future blasts out utopian visions like incantations from a magic cauldron. The incisive rhythm tandem of Edward Wakili-Hick and Tom Skinner provides the framework, as Theon Cross’s tuba acts as Son Of Kemet’s rumbling engine. Shabaka, both on clarinet and baritone sax, is the driving sentient force propelling this machine forward.

“Pick Up The Burning Cross” presents an early highlight, forging a formidable three-pronged alliance with two other visionary, and equally well-travelled peers, Moor Mother and Angel Bat Dawid. The former, a firebrand orator for free-jazz outfits such as Irreversible Entanglements, truly feels entangled within this track, lacing her seething words between the gaps in almost serpentine fashion. The proclaiming voice bellowing overhead is Shabaka’s sax, frantically leaning into a sense of dread and confusion. His playing gets so piercing that at times, it feels like a million needles stabbing the heart. It channels the reality of how messed up the experience of collective trauma is today: not through frayed impressions from faded photographs or ancient documents, but through the lens of our smartphone cameras as it is happening.

Where Your Queen Is A Reptile still brought some intellectual and historical context into the equation, Black To The Future gives you no quarter: this is music stemming from a primal, emotional impulse. It doesn’t always come from pain and suffering, mind you, but from joy, celebration and tranquility in equal measure. Just listen to the astounding way Sons Of Kemet transform into an ambient band on a whim in “Envision Yourself Levitating”: its ecosystem of plants rustling, birdsong and streaming water gaining consciousness in the shape of a honeyed Two-Tone/jazz workout, one that finds even Cross playing light on his feet. It feels like an honest yet surreal paean of daily ritual – in this case surrounding yourself with nature’s untethered beauty and mystery, something Hutchings mentioned doing in an interview with Esquire.

“Hustle”, featuring rapper and poet Kojey Radical, subtly leans into its loose-limbed groove, often leaving space for the drums to generate gusto. Here, Shabaka’s playing takes a firm backseat, like a caretaker guiding you through a dark, cavernous corridor. It’s the same kind of tenderness producers like the late Ras G and J Dilla show, extracting sounds from the past to make them palatable for the present – in their case, the hip-hop generation of the 90s and 00s. Laying down breadcrumbs to help listeners connect the dots.

Sons Of Kemet relay and circumnavigate the other half of that circular process again: knitting together those dense sampling methods with the more organic lingo of instrumental music, adding another layer to this ever-expanding helix. Like anyone daring to take a glimpse into the future, Hutchings is met with confusion, astonishment and alienation. Fortunately, he assimilates the tools, knowledge and creative bandwidth to acutely document them, and more importantly, navigate them in a useful, inherently joyous way.

“Let The Circle Be Unbroken” truly sounds like something existing from the beyond. To bring up one of my own silly millennial science fiction reference points, I had to think about those scenes in Contact where Jodie Foster’s speech gets all garbled and distorted as she travels through the wormholes. The way Hutchings wields his instrument captures a similar type of delirium; the cacophony and strange revelation of traveling beyond the constraints of physics or sensory perception. His sax – an instrument designed to emulate the human voice – really does sound like an actual human voice here: as if it’s speaking in tongues, or some kind of kooky dead language. It’s haunting, riveting stuff.

Indeed, this is music that has its finger firmly pressed against the pulse of the earthbound issues, and all evidence lies in the records Hutchings helped create in the not too distant past. On Sons Of Kemet’s second album, 2015 Lest We Forget What We Came Here To Do, the ‘we’ addresses all those oppressed and displaced by colonialism, genocide and racism. The record opens with “In Memory of Samir Awad”, commemorating a Palestinian boy killed by Israeli forces back in 2013. Eight years into the future, the cycle of violence against Palestine remains.

Which brings us again to the notion of constant movement and reinforcing that proactively and empathetically. Black To The Future, in both its taut and tranquil manifestations, reminds the listener that activity starts by examining the strife that festers within. And, in that pursuit, hopefully, none of us stand completely alone.