Being derivative isn’t necessarily a bad thing. As the adage goes: imitation is the highest form of flattery. Or perhaps it’s just wearing your influences on your sleeve? Can it be nothing more than a regular old homage to those who came before you? (Or just using “the letters of the alphabet of music,” as Ed Sheeren’s lawyer put it to a jury.) Whatever you call it, it’s often inevitable in some form or another. Success then comes from playing the cards and the crowd right. Jet are still just a one-hit wonder after ripping off Iggy Pop, while Led Zeppelin imitators Greta Van Fleet aren’t content with the sky being the limit, naming their forthcoming album Starcatcher.

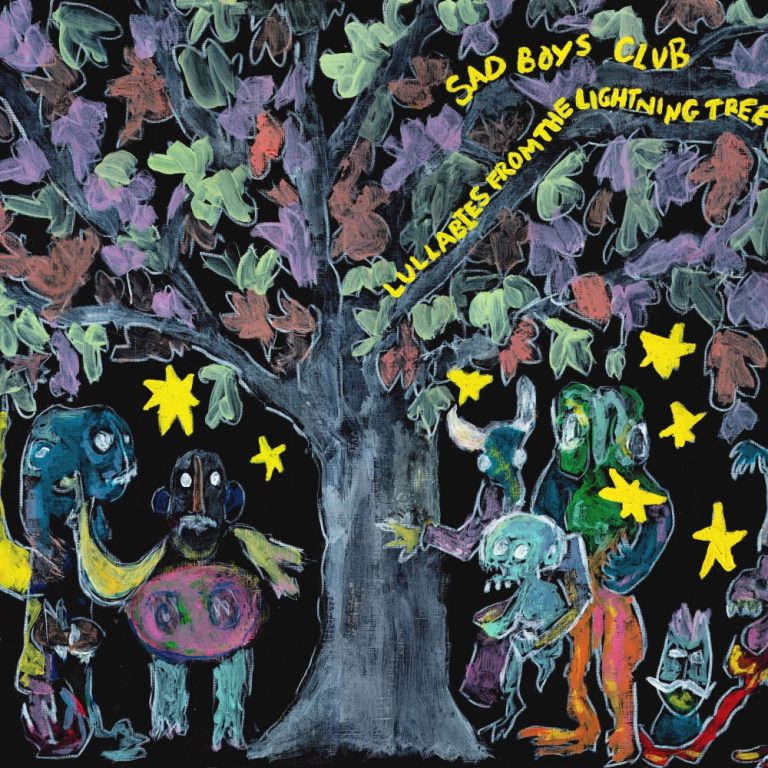

Is it a question then of how much you lean into it? London-based four piece Sad Boys Club seem to know what they’re doing. Since they emerged in 2017, they’ve been trying to find that magic place between hat-tipping to their peers and forging their own path forward. Their long awaited debut album, Lullabies From The Lightning Tree, is their most defining statement to date, a set of coming of age reflections happening after they’ve lived through their 20s. Reckoning with the highs that don’t last forever, they try to make their own – or failing that, recreating those they were inspired by.

Just look at the choruses to “Cemetery Song, 20/5” or “2bites2it” and you’ll be convinced that the 1975’s Matt Healy was in the recording booth laying down cuts for a new album. “We are mirrors / Reflecting mirrors,” frontman Jacob Wheldon rallies, not letting in if he’s in on the joke or not. Come the garish “Coffee Shop” the band aren’t even hiding the fact they’re making a Weezer parody song. “What they thought was a twitch / is my eternal bitch,” Wheldon struts, capturing something between a Mick Jagger and Rivers Cuomo impression. Is poking fun also a form of flattery?

And to the band’s credit, Lullabies From The Lightning Tree has a lot of fun where possible. Closing track “(You’re) All I Ever Wanna Do” is all freewheeling, fratboy Springsteen-ian energy (complete with a closing riff right out of the Illinois Jacquet playbook) and it’s one of the most infectiously enjoyable moments. Likewise, opening track “Peak” doubles down on its raucous emo energy, Wheldon giving a frenzied wink when he sings “I’m gonna peak if I get any louder” before the band throw the amps up all the way for the song’s final moments (eliciting an enjoyably exasperated “fuck me, jesus christ” from one of the bandmembers in the studio). You may have heard many moments from Lullabies before in some form or another, but at its best it’s still a heck of an enjoyable ride.

Oddly where the band lose themselves is when they indulge their habit of overdoing it that bit too much. “Coffee Shop” is fun once or twice, but a sore thumb before long (and sitting through the studio chatter at the start of the track repeatedly becomes tedious even more quickly). “Lumoflove” is the album’s one proper ballad, but Wheldon almost seems afraid of allowing an intimate moment to emerge, resorting to a yelp whenever a moment of tenderness appears.

Elsewhere on “The Cracking Song” he’s channelling his best Matt Berninger with a line like “I felt something was wrong at the Academy drinks”, but despite it matching the chorus’ sentiment, the song is overfraught and clunky. Wheldon may be in a reflective mood for most of the album, but he doesn’t have the lived in ache to make his sometimes unwieldy phrasing hit deep into your gut.

Lullabies From The Lightning Tree might have been a long time coming, honed from experience and hard work on the live circuit (including tours with Spector and Bombay Bicycle Club), but it still sounds restless and living under a shadow cast by peers of the band. Sad Boys Club have a knack for finding that familiar sugary moment and giving it new clothes (credit too to by bassist Pedro Gontijo Caetano Barroso Leite who also produced the album). But there’s only so many ways you can dress something before it becomes obvious you’re just copying style and emulating substance. Sad Boys Club aren’t there yet, but Lullabies’ most derivative moments tempt fate by asking the listener to remember that familiar high and relive it in a different light. Before long it becomes apparent that it’s just influences on the sleeve and there’s no surprises hiding up inside it.