For Daniel Lopatin, the process of making music has never been one solely of creation, but also recontextualization. His debut release as Oneohtrix Point Never, 2007’s Betrayed In The Octagon, was composed entirely on the Roland Juno-60 synthesizer; a device that was invented in 1982, brought into the mainstream consciousness by synth-pop groups such as Eurythmics and Duran Duran, and subsequently treated as a relic of a cheesy, bygone era before being repopularized in the mid-2000’s by indie-electronic artists like Phoenix, Clap Your Hands Say Yeah and Junior Boys. In the midst of this revival, which saw the Juno-60 being used with similar intentions to those it was popularized under, Lopatin arrived with a series of releases (later collected in the Rifts compilation) that recontextualized the instrument by using it to craft spacey, sci-fi indebted analog textures. 2010’s Returnal saw him taking this idea one step further, layering drones on top of each other for dense psychedelic effects and adding noise to the mix; while 2011’s Replica, his breakthrough effort, found Lopatin abandoning the Juno-60 for the most part in order to make sample-based music that refracted images of the past using corrupted loops, underlined by pretty piano melodies and with ’80s television ads as the source material.

That album constituted a considerable reinvention for Lopatin, but, like his earlier work, it also saw him recontextualizing widely-dismissed sounds into completely different functions. It wasn’t an exercise in nostalgia so much as it was in finding new possibilities for these sounds. And now on R Plus Seven, the newest and best release under the Oneohtrix Point Never moniker, he’s done it again by returning to synthesizers, along with an assortment of other instruments and tools, for his brightest and most immediate work yet.

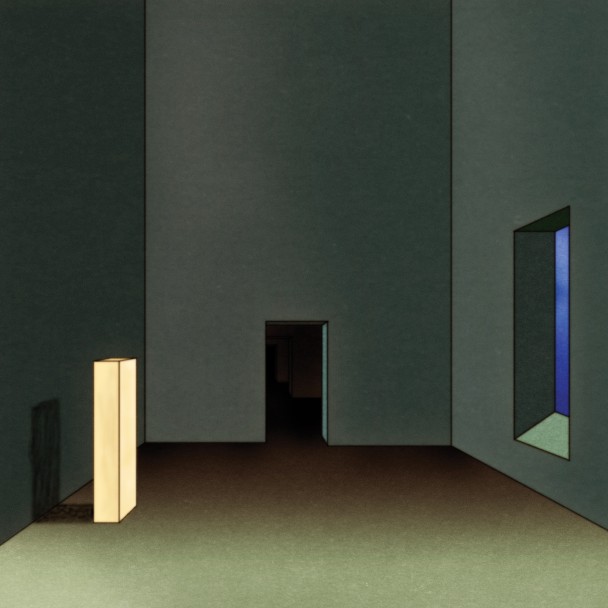

At a time when availability has made music more disposable and prone to be taken at face value than ever, R Plus Seven begs to be explored, like the series of rooms implied on the cover, from a conceptual standpoint as well as an outright musical one. Where previous OPN releases explored themes of recyclability, decay, feedback loops and drawing humanity from the digital realm; the focus of R Plus Seven is on morphogenesis, procedural composition and cryogenics. Lopatin does this by presenting R Plus Seven with a piecemeal structure where the majority of tracks consist of one or two recurring motifs that are interrupted by a revolving door of ideas.

Take “Zebra,” for example. The central idea to the first part of the song is a bright, glossy, programmed staccato synth progression that introduces the track before Lopatin brings in processed human voices that ebb and flow along with the main refrain, eventually overtaking it before the main progression comes roaring back. The cycle repeats itself, with stately piano lines and an assortment of samples augmenting the main melody on the second turn, before Lopatin does away with the idea entirely in favor of tense, vibrating percussion, sealed in a static ambient space. After that, the song’s coda consists of chopped synthesizer samples that set the bedrock for a saxophone outro. The lively synth progression in the first part of the song is an exercise in procedural composition, the claustrophobic ambient space of the second part a representation of cryogenics, and the way the song progresses from section to section, with parts building up before splintering off into something completely new, is entirely morphogenetic in form.

There’s a tendency for the kind of experimental electronic music OPN is known for to be dour or serious in tone, but one thing separating Lopatin from his potential competitors is that his music has always explored a wide spectrum of emotions, sometimes within the same song. Although there are moments of undeniable sadness on R Plus Seven, such as the processed chorus that crops up at the end of “Still Life,” there’s also humor inherent in Lopatin’s use of a grunting sample in “He She,” playfulness in the way “Americans” toys with horns and field samples, and so on. From an emotional standpoint, what Lopatin is doing here has much more in common with ’90s IDM acts such as Mouse On Mars or early Boards Of Canada than with current contemporaries like Emeralds or Tim Hecker. While conceptually heavy, the concepts on R Plus Seven are employed in a manner that’s highly enjoyable from a traditional standpoint – you don’t need to understand cryogenics or even know that they’re being portrayed for this album to appeal to you any more than you need to understand the symbolism in a beautiful painting in order to enjoy looking at it.

The most moving moments on R Plus Seven are the ones that release the tension of Lopatin’s most hermetically-sealed compositions, like a cell undergoing cytokinesis: the delicate piano that cracks open the main synth progression in “Zebra,” the sterile organ break that interrupts “Problem Areas,” the disorienting side-chain effect that forms the apex of “Still Life,” and the swelling pipe organ outro of “Chrome Country.” Here, Lopatin excels at what he’s been doing since his first release as Oneohtrix Point Never, and what first brought us to him: drawing feeling out of the digital realm, instead of just channeling it. After fearless reinventions of sound on three consecutive releases, it’s good to know some things never change.