Artists take breaks all the time, and for various reasons. There were the infamous six years between Fiona Apple’s second and third albums where the project was stymied by label issues. She then went on to wait even longer between releases. There are bands like Portishead, who come back from an 11-year break to put out the long-awaited Third, only to virtually vanish again. And there are bands like The Fiery Furnaces, who put out a staggering eight albums in six years, but have been on hiatus since 2009 while the duo work on their individual solo projects.

In the music world, a few years between releases can feel like a lifetime, and usually the context for why an artist took a break wouldn’t (or, perhaps, shouldn’t) necessarily have a bearing on the record they return with. But 12 years ago, acclaimed singer-songwriter Nina Nastasia put out her most grand and dramatic album yet, with 2010’s magnificent Outlaster, and then — poof. After touring that album, she practically disappeared from the scene, only popping her head out for a one-off show here or there. Finally, in 2018, fans who had sort of resigned themselves to the idea that she may never return were greeted to a single: “Handmade Card”. It was a Christmas song of sorts, and it came with the promise of “more soon.” But more wasn’t materializing, and Nastasia went back into the mist.

Now, four years on, we finally have her seventh album, Riderless Horse, and, for better or worse, the context of her time away matters. It’s the pulp of much of this record. In those intervening years — as one can read much more deeply in this fantastic, piercing, and upsetting interview with The Guardian — the once rather prolific Nastasia stepped away from music and into the confines of an increasingly difficult situation. Her life, which she shared with her longtime romantic and musical partner Kennan Gudjonsson, was spent mostly away from the spotlight, and eventually, people in her circle saw less and less of her. Their relationship became more and more toxic over time, and the emotional abuse rendered Nastasia unable to continue creating. Although the two never physically abused one another, there was a poison there, like a black hole. Finally, she decided enough was enough, and she knew she had to leave, so she made the difficult decision and moved out of their small apartment they had shared for years. The very next day, Gudjonsson committed suicide.

The weight of that experience — from beginning, through the muck of the middle, to the tragic and confusing end — is important here, because it lends so much of itself to the content of Riderless Horse. One of Nastasia’s gifts as a songwriter is her ability to get inside the mundanities of life and relationships — almost no one writes about conversations, of things said and unsaid, like she does. But now, with this new batch of songs written in the wake of this devastating blow, Nastasia hones in on her own tragedy – the beauty as well as the darkness – of the life she had to leave behind, and the one she wants to lead now.

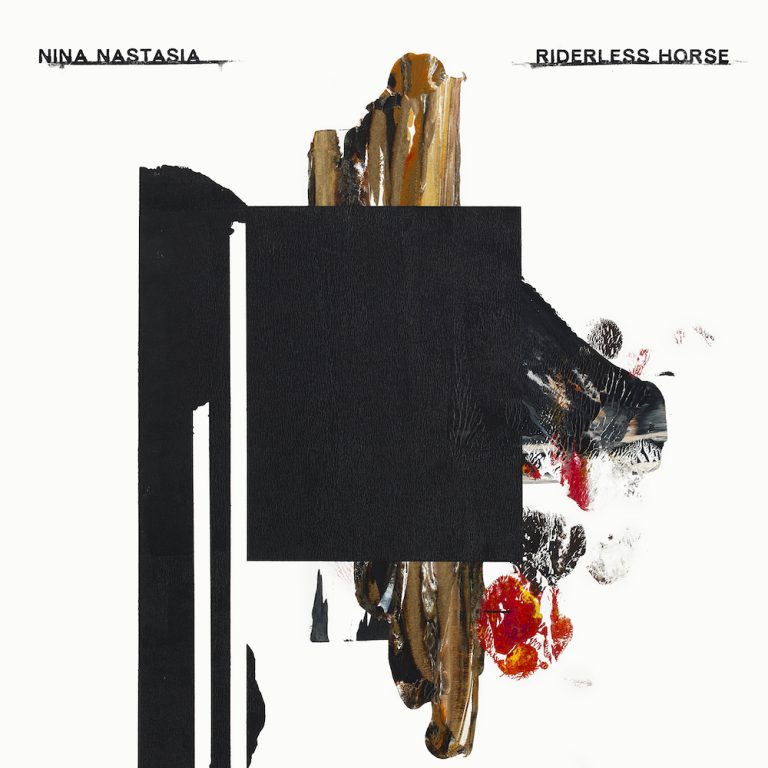

Beginning appropriately with the sound of her uncorking a bottle and pouring herself a drink, getting ready to tell us a story, Riderless Horse is being called her first true solo record. Though she’s working again with Steve Albini (who has had some hand in either producing, engineering, and/or mixing all of her records) and producer Greg Norman, and despite the fact that all her records have bore her name, Nastasia considers it her first solo album for a couple reasons. For one, the only instruments featured across the 12 proper songs are her voice and her acoustic guitar. It’s nearly as spare as one can get. But, more deeply, this is the first album that Gudjonsson did not have a hand in producing. He had done more tinkering and monitoring of her work — right down to lyrics, melodies, and artwork — than fans most likely ever knew. Now with Riderless Horse we get a completely undiluted Nastasia, a version of her where she gets final say, where she gets to call the shots.

And what a version it is. A veteran of the minute detail, Nastasa writes about the perplexities of losing someone you love and resent, whom you admire and whom you deeply fear. The 12 years away and the shedding of her previous strictures have done nothing to dull her pen. You might not guess this is the backstory of the album given the rather upbeat melody of the first song, “Just Stay in Bed”, but just take a look at lyrics like “I like it here in bed / Alone when I’m feeling dead / Death is a terrible place to stay long”, or the line about a slow drip of poison, and you start to get the gist: something’s amiss here. Nastasia writes with a frankness that’s at times startling, even for a woman who once sang, “I always dreamed of the day I would bury you / I never thought on that day I’d stop hating you.”

The barbs keep coming, and her voice, which has always been a thing of straightforward crystalline beauty (she sang once, perhaps half-joking-but-not-really, “I have perfect pitch” in a laconic low droll), is also pushed to some raw places. “You Were So Mad” has her belting in her high register, before settling down for the gently sad “We’ll go our ways / We’ll fight we’ll hate / For now until the end / We’ll ask ourselves what have we done.” On “Ask Me”, her voice ambles blurrily through melodic runs as she asks questions like, “What is it you want from me?” and on “Lazy Road” she seems to quote Shakespeare (“To bed, to bed”), taking the guise of one of his most complicated female heroines.

Eventually, we start to hear her resolve building up. On “The Two of Us”, she sings, tragically, “You might hate yourself and fall down flat / But I don’t have it in me now / To pull you up and back.” On “Go Away”, she sings in a low radiator hum of a delivery, “You slow me down / You make me weak / Go away go away and leave me be.” Listening to this album, it is clear that Nastasia was put through the ringer, and did come out the other end, but it wasn’t a smooth journey. Experiences like this are profoundly specific, and immensely nuanced and complex. She has said she does not wish to villainize Gudjonsson because, for all his flaws and all the manipulation, there was also love there, and it doesn’t just evaporate. How could it?

But the bleakness is rife, and the pain of her experiences give the album an at-times uncomfortable tension, like when your friend tells you details you may not have wanted to know but you know it’s important to hear them. On “This is Love”, the first line reads: “Is this love? It feels so bad”, which tumbles into the painful resignation “I guess I’ll just stay in hell with you if this is love / Throw a punch or two and take a few then rise above”. Later, on “Blind as Batsies”, she acknowledges “I love you and I know you love me”, even while they exchange blows and “tumble home with broken bones.” And on “The Two of Us”, we get one of the saddest verses: “The two of us make one / Deep in the shit trying to crawl out of this dung / The stink of it overwhelms the good we’ve done”.

And perhaps that is even some sort of mission statement for the record. Nastasia has deeply conflicted feelings about this person who contributed so much to her life, but also took so much from it. Across the 12 lyrical songs (the closer is a placid field recording), you could pull out a line or two from almost any corner and find some scarily blunt or emotionally candid observation. The album may be a little homogenous for some listeners, but this is a narratively and emotionally precise set of songs, set to sneakily indelible melodies. Nastasia has never written with such vivid truthfulness, such earthen brutality.

Riderless Horse is a quiet exorcism, in communion with ghosts, deceptively dressed up in as little and as simple clothing as possible. Nastasia is acknowledging, openly commenting on, and attempting to process and shed these layers of cyclical pain, abuse, and disorder she’s experienced for so much of her life, including (perhaps most achingly) her time away from the business. There are no easy answers in times like this. But she knows now that it’s worth it to keep forging ahead, to have hope. As she sings in the very final moment: “I want to live / I am ready to live.” At the end of the day, what else could you hope for?