Musically and in terms of production, Nicole Dollanganger’s early EPs and LPs mined DIY and emo-folk templates. Lyrically, Dollanganger drew from true-crime archives, abnormal psychology, and horror fiction (and, presumably, her own life). Over numerous projects, she honed a distinct vocal timbre and set of atmospherics, her waifish delivery floating in reverb-soaked limbos. Volatile fragility, camouflaged predation, and desperate love likely to turn violent are recurrent themes.

Dollanganger’s descriptive talents and penchant for creepy mise en scènes culminated with 2015’s Natural Born Losers. In “Poacher’s Pride”, the singer shot an angel and starved it in her basement. “White Trashing” included the line, “it’s really hard / to scrub the dog piss out of a white trash heart.” On “Angels of Porn II”, the singer’s voice was alternately strained and wispy, a trashy electric guitar cutting across the sonic field. The song references extreme isolation as well as torture and rape at the hands of a mysterious jailer, who may be the self, an abductor, or, metaphorically, God/life itself.

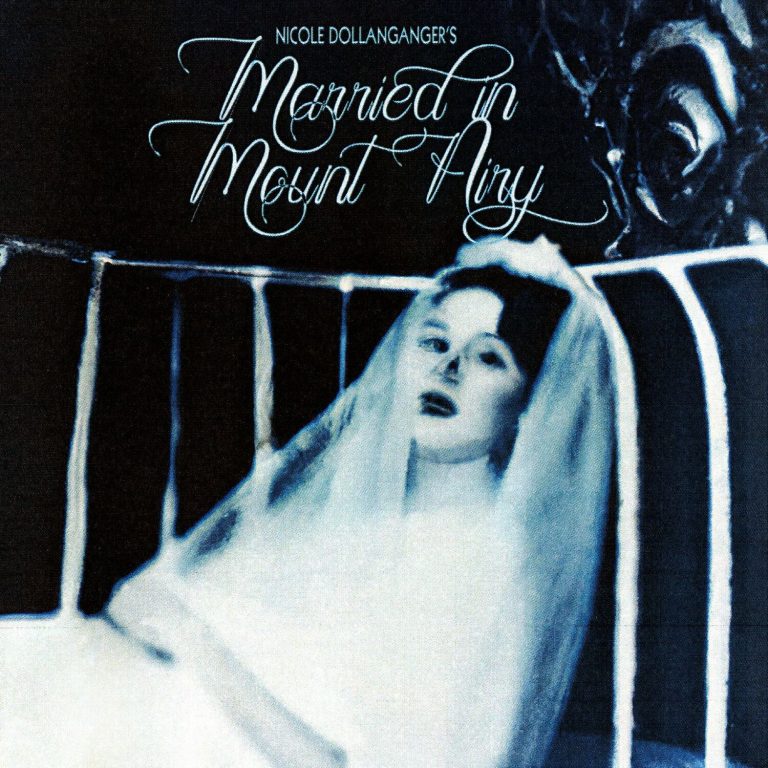

With her new album, Married in Mount Airy, Dollanganger builds on the more ambitious instrumental nuances forged on her last album, 2018’s underrated Heart Shaped Bed. Acoustic and electric guitars, synthy accents, and occasional drums interplay dynamically. Lyrically, she mostly backburners the graphic narratives and pathologizing portraiture of earlier work, gravitating toward lyrics that more singularly address grief and longing. The result is her most conventionally rendered sequence, tracks that may further enroll sad-pop fans while possibly disgruntling listeners who gravitated to her previous work for its more disturbing content.

One of the more riveting tunes in the Dollanganger oeuvre, Married’s opening title track addresses the intersection of idealism, modernity, and decadence, rewriting the biblical fall from grace. Doesn’t quaintness, the song suggests, often mask monstrosity? Haven’t we learned that rectitude and sin typically go hand-in-hand? Midway through the song, drums enter the mix, the piece taking on a more apocalyptic feel. “There was something strange in the air,” Dollanganger moans, invoking a palpable anxiety.

“I can smell the blood purged from raw steak / by the barbecue on a summer day / in the sun,” she offers on “Gold Satin Dreamer”, a Rockwellian image given the Lucian Freud treatment. “Dogwood” is Dollanganger’s take on the traditional love song, an eerie prayer for her addict-partner not to die. With “Runnin’ Free”, Dollanganger reaffirms her penchant for small-town environs, bookending the tune with references to “this lonely 78 motorhome.” On “Bad Man,” she grieves the death of a lover who, she acknowledges, “had to go.” Her tone is less ambivalent or overtly adversarial than with earlier sketches of men/lover figures. Her voice is whispery, almost confessional on “My Darling True”, offset by thunderous chords and ethereal accents, her lyrics blending Harlequin sentimentality and tabloid noir.

While the opening half of the project effectively highlights Dollanganger’s segue from uber-fringy subject matter to more traditional depictions of tragedy and convoluted desire, the second half occasionally shows Dollanganger wavering in terms of pop savvy and listing into lyrical vagueness. “Moonlite” is rhythmically engaging and melodically sound, though as the piece unfurls, it loses emotional cogency. “Sometime After Midnight” is a mostly successful outsider take on the idea of “date night,” Dollanganger’s voice interwoven with an acoustic guitar and synthy background sounds.

With “Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus,” Dollanganger attempts to embrace lyrical obliquity, riffing on classical motifs. While intriguing sonics keep the listener engaged, the melody sags, elusive images failing to offer a sufficient access point. On “Whispering Glades” the instrumental mix is well-nuanced, even though character descriptions land as somewhat generic. Fortunately, the album ends with the poignant “I’ll Wait for You to Call”, a shimmering chronicle of unrequited love.

Ethel Cain’s Preacher’s Daughter, released last year, may strike some listeners as a likely analog to Married. While both Cain and Dollanganger plumb the canon of American Romanticism, however, Cain’s work is more bombastic, rendered through broad brushstrokes, whereas Dollanganger employs a more detailed, almost pointillistic style. Cain is a hyper-realist, indebted to Bat Out of Hell and Springsteen as much as Ezra Furman; Dollanganger is a melancholy impressionist, more gothy gospel than rock, more “Delia’s Gone” than “Born to Run”. Cain’s work bursts with motion and road references, compelled by a certain extroversion, whereas Dollanganger’s is more static, alluding to unmapped towns and windowless rooms, necessitated by a toxic brand of introversion.

One might also think of Lana Del Rey’s work, particularly pre-Lust for Life. LDR’s persona, however, is Hollywood-esque, glammy, and cosmopolitan, while Dollanganger’s songs tend to reference poverty and unglamorous settings, more Winter’s Bone or Jesus’ Son than The Great Gatsby. Also, sexuality in LDR’s work rings of gilded abandon and mythologized intimacy, whereas in Dollanganger’s work it frequently translates as fetishistic, pornographic, and/or exploitive.

If much of Dollanganger’s previous work was trauma-prompted and nightmare-inflected, Married in Mount Airy is more quotidian in its depictions of wounding and loss. While Dollanganger mostly accomplishes this shift in perspective, several tracks indicate that conventionality, as an experience and a source of inspiration, may involve conditions to which she will have to acclimate. How do we find beauty and horror in the everyday? How do we frame these findings in such fashion that our offerings achieve some level of aesthetic urgency? Numerous artists have navigated these crossroads. Dollanganger, no doubt, will find her new muses and her individual way.