There’s a certain lived-in quality that most mainstream country music seems to lack–an excess of polish and shine but a dearth of real substance. The pop hook has replaced any semblance of creative ability, and the songs sound out-dated from the moment you hear the first few notes. This has less to do with the subject matter, I think, and more so with the caliber of artist and material. However, there is creative and intriguing country music being produced, though you’re not that likely to find it on the radio or the national country music networks. Music from artists like Kelly Hogan, Lucinda Williams, and Lilly Hiatt who manage to subvert these ingrained expectations while also showcasing a swaggering vulnerability, which seems to be at odds with the modern country template. With her backing band, The Dropped Ponies, providing the calm and drive behind her honeyed vocals, Lilly Hiatt seems to inhabit the souls of country royalty like Tammy Wynette and Loretta Lynn with relative ease.

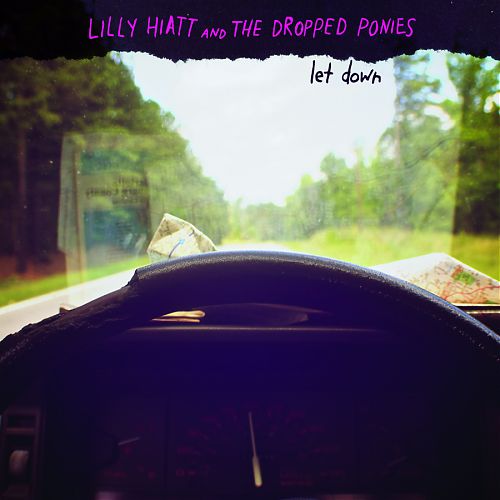

Like those rural, steel willed singers, Hiatt is able to tap into the fiery heart of the songs that stretch across her latest album Let Down. The fire smolders and singes everything it touches as she sings about the uncertainties of love and the heartache of walking away—away from a relationship, a person, just picking up and leaving everything. In her resolve, the songs develop a quiet intensity that simmers and churns just underneath her country façade, turning these traditionalist narratives into something vaguely threatening, something born from dark drives on endless roads and a need to escape. Let Down imagines that the pop aspects of mainstream country can be twisted and creatively undermined to show this often unfairly branded genre is capable of greater things than just what you hear on the local country music radio station—which is not to say that the record always succeeds, but it tries a damn sight harder than most of its bucolic brethren.

Between tales of determined women (“Championship Fighter”) and unsteady familial ties (“Angry Momma”, which bares more than a passing shade to something that The Drive-By Truckers would kill to record), Let Down is no stranger to recognizable country music tropes. In fact, the album seems to revel in the acknowledgement of its own musical roots. But Hiatt instills these songs with such a fiercely authentic independence that the cliché of the on-her-own woman is deconstructed and tenable emotional connections are created from what remains. With its clacking percussion and Hiatt’s twangy vocals, “Young Black Rose” plays free with the notion of the spurned lover and flips her liberty into an act of defiance. A casual slide guitar eases in-between lyrics such as “her thorns get thicker and her whole damn heart eventually will close” and “from the moment you saw her/knew she was a goner/she was a young black rose.”

She eases into “People Don’t Change” with a sadness imparted by lines like “wish I had a stronger heart” and “wish every time I loved a man, I did not fall apart” but there is a resignation that seems to acknowledge that she will always do just that. The guitar feels steeped in classic country yearning—something pulled from the George Jones or Merle Haggard Nashville-outsider rulebook. The band never fails to keep the song going and Hiatt’s vocals never fail to find that uneasy place between a lover’s intimate conversation and the drunk confessions of a lost soul. “3 Days” stomps along like a beat-up Cadillac looking for the last bar for 100 miles, kicking up dust as it flies down the road.

But the record can veer too close to overly maudlin tales of down-on-your-luck people at times, and during those few moments, the album loses some of the luster that sets it apart from the ever-growing crowd of banal country singer-songwriters. Thankfully, these are only infrequent occasions and never seem to last very long, and the album never dwells on what it might have done better in retrospect. It pushes forward and leaves the second-guessing to those left behind. Let Down ends with two heartbreaking tales of love and loss, the traditional-minded “Knew You Were Coming,” with its ghostly slide guitar and vocals that would make a statue cry, and “Big Bad Wolf,” a rocker that blows the top off a southern ride and then stomps on the gas, racing toward the horizon.

As the daughter of singer John Hiatt, Lilly is no stranger to the history that she is actively participating in. And on Let Down, she channels the ghosts of country greats, and though the shoes may feel too big at times, she is able to hold her own with these hallowed artists of the genre. While their constant presence could have unnerved other singers, Hiatt feels a common link and an affinity for these artists that keeps her walking comfortably side-by-side with their spirits, conversing in that shadowy speech that only ghosts and the heartbroken understand.