Lana Del Rey’s 2012 debut Born To Die was the album that gave birth to a seemingly endless number of op-eds and social media firestorms. A divisive SNL performance, the revelation of her past Lizzy Grant era, her stark statements to the press and her unpolished portrayal of femme-fatales invited harsh words by everyone from Brian Williams to Kim Gordon and Frances Bean Cobain. When Del Rey criticised Ann Powers’ thoughtful, largely favourable review of her 2019 classic Norman Fucking Rockwell!, even some fans wouldn’t defend the singer’s rebuke of one of the most revered living critics. But given the firestorm of criticism Del Rey had faced up until then, her defensiveness was at least understandable.

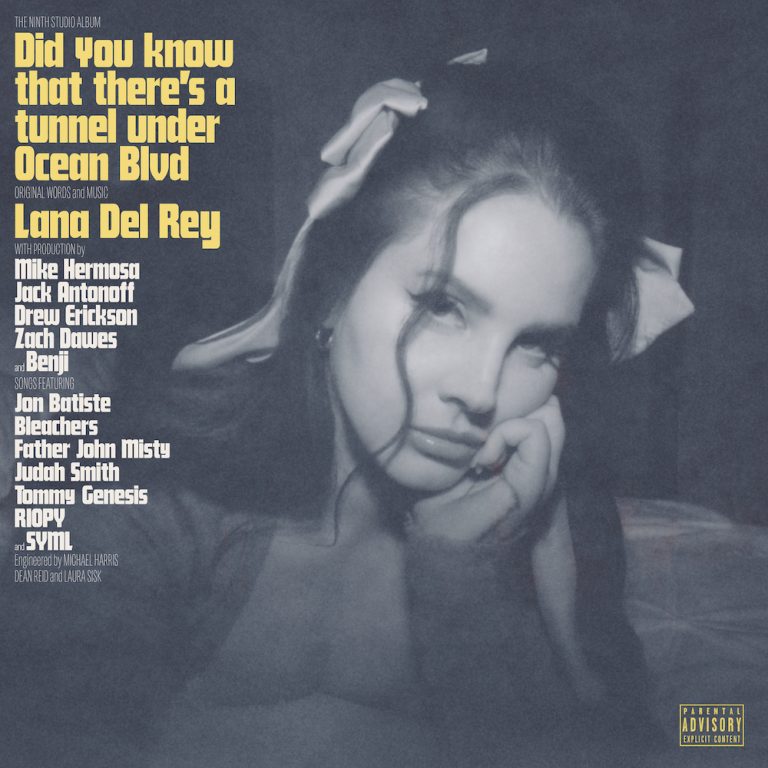

If Del Rey rejected the idea that her musical identity had ever been a persona – the central sticking point in her feud with Powers – Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd is the album that makes this point most clearly. It’s long, often shockingly confessional and orientated around family and questions of an existential nature. It’s the sound of an artist with nothing left to prove zooming out and examining with disarming clarity their own legacy and mortality.

On opener “The Grants” she enlists Melodye Perry and Pattie Howard (former backing vocalists to Whitney Houston) to assist in an ode to her family. The bridge surely represents one of the most emotive musical moments of Del Rey’s career thus far, as she considers the memories she wants to hold on to as she dies – from the birth of her sister’s first child to her “grandmother’s last smile”. Del Rey has long been reduced to the label of “sad girl music”, but in the song’s final line, she lingers on grace, “It’s a beautiful life / Remember that too for me”.

Ocean Blvd might be the pop star’s most melancholic album yet – as compelling as Born To Die or Ultraviolence’s tales of destitution may have been, there’s a newfound heaviness here, as Del Rey testifies to existential dread and lingering isolation. The LP continually scratches at an uncomfortable question, what does it mean to enjoy boundless success – to achieve your wildest dreams – and to still feel incomplete and unfulfilled? The title track is the purest encapsulation of this, as Del Rey draws similarities between herself and the forgotten, sealed-up tunnel underneath Ocean Boulevard. In the song’s second half, a rich arrangement of strings, drums, guitar and clarinet swell, as the singer pleads, “Don’t forget me, like the tunnel under Ocean Boulevard.” Never before has her music sounded quite so desolate and never has she sounded quite so alone at the microphone. Earlier in the song, she references the 2:05 minute mark of Harry Nilsson’s “Don’t Forget Me” as a moment of immense musical power; the 3:52 mark of this song will surely go on to hold similar significance for countless listeners.

Now 37 years old, Del Rey seems acutely aware of the expectations placed on women of her age – the milestones they’re expected to reach (marriage, childhood) to be deemed worthy and whole by society and the ways in which their stories are flattened and disregarded in favour of those from a younger cohort. This anxiety, and the sense of urgency it produces, ripples throughout the album, as she examines her fitness to be a mother on “Fingertips” and addresses assumptions that powerful men in the industry must be responsible for her success on the verbosely titled “Grandfather please stand on the shoulders of my father while he’s deep-sea fishing”. “When’s it gonna be my turn?” is the question that dominates the title track – an instantly relatable sentiment to anyone who’s felt unable to reach the same milestones at the same time as everyone else around them.

The disparity between societal expectations and reality is addressed most fully on “A&W” – a bewildering epic that condenses decades of experiences into seven minutes. The first half – detailing “the experience of being an American whore” – offers unsentimental mourning of prematurely lost innocence, tales of sordid, loveless, sexual encounters and the story of one person descending into society’s margins. To listen to Ocean Blvd as a music critic is often to feel as though Del Rey is speaking directly to you; anticipating and responding to your various initial reactions in real time. On the second verse of “A&W”, she shrugs off those who are still confounded by her complexities and contradictions; “Ask me why, why, why I’m like this… I don’t know, maybe I’m just like this”.

In the song’s second half, the simplicity of the pulsating, repeating piano line is replaced by the sort of imposing trap beats not prominently featured in the singer’s output since 2017’s Lust For Life. Self-destructive love remains the central theme, but this time with a magnified focus on a fickle and transactional lover “Jimmy”. Though, this time, our narrator gets the last laugh, as she signs off, “Your mom called, I told her, you’re fucking up big time!”

Ocean Blvd is a compelling, extensive excavation of Lana Del Rey herself, but more crucially, it is an album about loss and how we choose to respond to its spectre. The four-track run between “Kintsugi” and “Grandfather…” offers a stark reminder of death’s disarming power – the simple truth that, as Sleater-Kinney once sang, “we’re all equal in the face of what we’re most afraid of”. “Kintsugi” takes its name from a Japanese philosophy that views breakage and restoration of objects, usually pottery, as integral parts of its history and ongoing existence, rather than flaws to be concealed. So much of Lana’s past work has centred around world-building and self-mythologising, but here she’s at her most evocative during straightforward confessionals – “Daddy, I miss them”, she croons, reflecting on the loss of three family members within the course of a single year. The almost-acapella song represents Ocean Blvd’s quietest moment – the sound of a sensitive heart slowly trying to repair while preparing for a world sure to break it again in due time.

On album centrepiece “Fingertips”, Del Rey completely disregards traditional pop structures in favour of an all-verses song that plunges ever greater depths with each successive verse. The third verse finds her pleading with her brother to stop smoking, while the fourth tells of needing to be medicated to survive and of her uncle’s suicide. The fifth tells of her real-time reaction to the news of the passing, the sixth of her teenage suicide attempt and the eighth of her mother’s cruelty in sending her away as an alcoholic teen; “never to come back”. There’s an elite tier of Lana songs whose depth and power leaves one’s mouth agape upon first listen – “The Greatest” and “Hope is A Dangerous Thing…” spring to mind – and “Fingertips” surely joins the club.

Even on the album’s most awe-inspiring, lovestruck moments, there’s an unshakeable sense of bittersweetness – of Del Rey being a spectator of joy rather than a recipient of it. This potent cocktail of feelings is evident on “Margaret”, a song written by Lana as an ode to the love shared between her collaborator Jack Antonoff (who is featured here on vocals) and his wife Margaret Qualley. Here, it’s hard not to hear Del Rey sing of love’s comforts and salvation without being reminded of that piercing question at the title track’s core: when’s it gonna be my turn?

Like any good, honest work of self-exploration, Ocean Blvd is sprawling – it’s Del Rey’s longest album to date by some distance – and not without the occasionally questionable choice (an interlude from a controversial pastor to the stars, an incongruent, trap-heavy final three track run and, an extensive sample of 2019’s “Venice Bitch” on the closer that undercuts the album’s singularity). But the best moments, which abound, solidify Del Rey as one of the all-time greats. At the end of “Fingertips”, she sings “I just needed two seconds to be me”, but it turns out that her doing just that for 77 minutes straight is pretty glorious too.