On Friday evening, I looked out of my window, and observed that the neighbours across from my were sitting on a couch, glued to the beamer image of Kendrick Lamar‘s new album on the wall in front of them. In the split second my eyes hit their window it was clear that the small group of white, mid-20s people in the room were looking at GNX, which just surprise dropped about two hours earlier, the same way reserved for a Game of Thrones episode: a cultural moment of reception, that stopped the world for an hour or so.

Now, the context of this scene matters: it’s a group of white, suburban, middle class zoomers, who can afford a flashy projector, staring at the image of a black man that’s entering his late 30s, reading his music like a hyper-text of immediate and significant cultural relevancy, even though their physical, spiritual and economical reality is far removed of the life led by most black people in America. By the time you read this review, you’ve probably already heard the record a dozen times or more, probably combed through TikTok, Instagram and Reddit explanations of the lyrics and shared a couple of memes that remixed the artwork. But, did you really listen?

OK, maybe that isn’t your fault. Kendrick has conjured a quite hypnotic spiral in the 2020s, so far. If you’ve read my year end analysis of it, you know of the elaborate therapeutic value of the tectonic 2022’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. And there’s no way you haven’t somehow engaged in this year’s battle between Kenny and Drake, which had Lamar obliterate the latter’s legacy in a cultural moment that could eventually end up the defining moment of hip hop’s struggle between mainstream value and revolutionary aesthetics. It’s a gift to experience Lamar’s work as it is still in the making, it’s possibly our generation’s equivalent to boomers living through the climactic evolutionary era of Bob Dylan. Yet, unlike with Dylan, the larger Kendrick’s catalogue grows the more present appears a central question: who is this music really for?

Internet essayist F.D. Signifier elaborated on this question in a monolithic video essay, which observes the evolution of hip hop as a genre and black music as expressive art before diving fully into questions of politics, capital, stature and class. Black art has always been commodified, if not by white hipsters that entered black spaces to assimilate unique vernacular as fashion then surely by rich white execs who fed art and artists alike to the music industrial complex. In this process, the art progressively morphed into a simulacra: the simulation of ghetto slang, black heritage and gangsta postures was ultimately read as reality by white middle class kids who fetishised what’s ultimately a heavy burden of marginalisation.

Kendrick’s records, elaborate in their intellectual depth and rich with conceptual density, were about the black experience, but they also fulfilled a function of translation that the woke white millennial and zoomer generations could applaud without feeling, well, endangered to subscribe to dangerous aesthetics that are a little too spicy for them. Mr Morale…, in that equation, didn’t just seem like it was geared away from that audience group – the record practically held a “House of Leaves”-like declaration of “this is not for you” over it. Progenitor “The Heart pt. 5” bravely declared “I want the hood!”, and “Not Like Us” is – decisively so – about the tension among black people who chose polar career paths: the exploitative (even abusive) performer and the genuine poet.

Now, I love Kendrick’s work, and I am white and fairly middle class, so I don’t erase myself from this problematic dynamic. What I will do instead is point out that Kendrick has, for the first time in his career, chosen to abandon the art-school conceptualisation of his work, and has instead made a record that does away not with the white experience alone, but focuses solely on black aesthetics. “I want the hood!” comes to mind when listening to GNX: this isn’t just Kendrick writing about black perspective in a progressively maddening world, or diving into the unconscious parts of lived trauma unique to black culture. It’s a record that doesn’t care about me, or any fellow white listeners, or anyone that is not inherently affected by rap. It explores the genealogy of West Coast rap similar like Denzel Curry did on his latest album with Southern hip hop, with both albums aiming at recapturing a purist experience.

Of course there’s tons of fun here, and tons of intellect and craft in Kenny’s bars, but how many white listeners will hear opener “wacced out murals” and get the aesthetic connection to Luniz’ “I Got 5 On It”? And I don’t just mean the beat, but also the imagery: where Luniz was rapping about spare change and the flow of dollar bills, Kendrick now sneers at the currency evolution of Bitcoin in light of the old guard of rap ageing into business men. “N____s from my city couldn’t entertain old boy / Promisin’ bank transactions and even Bitcoin / I never peaced it up, that shit don’t sit well with me / Before I take a truce, I’ll take ’em to Hell with me”.

There’s two prominent moments of self censorship in the track – which is really curious. One is in the opening verse, of “I paid homage and I always mind my business / I made the —“. And then one later, when Kendrick presents what’s pretty much the thesis of this phase in his career: “Okay, fuck your hip-hop, I watched the party just die / N____s cackling about — while all of y’all is on trial”. Is Kendrick cutting out a specific person? Unlikely, considering he namedrops Lil Wayne, Snoop and Nas early on. And the track confronts adversity as the shape of a monstrous entity of posture that morphs into black rappers more so than one specific person: “You ever ate Cap’n Crunch and proceeded to pour water in it? / Pulled over by the law, you ridin’ dirty, so you can’t argue with ’em? / Then make it to be a star, bare your soul and put your heart up in it? / Well, I did!”

This demon of inauthenticity that haunts most of GNX is banished simply by… well, bangers. There’s not a single album that’s hitting as hard, that’s as club ready in Kendrick’s catalogue as this. DAMN. has that mainstream appeal, but more so in expanding into the territory of arena acts and radio POP (all caps), with Rihanna and U2 guesting. It wasn’t really a club record that you could dance to, it wasn’t intruding on the turf that, for example, Drake claimed. It didn’t have a heartrending ballad like GNX‘s “luther”, which is a pretty straight Y2k duet with SZA, existing just for the sake of its utter beauty, without Kendrick ever straining the track to fit a larger message.

And even when there’s a message, such as when Kendrick confronts a life of hard work and stark sacrifices on “man at the garden” or when he ridicules the music industry on “hey now”, the words easily translate into a chameleonic anthem that a lot of marginalised people can relate to. It is possible to just focus on GNX as a collection of bangers, of body music that eludes whiteness. But that also ignores its deeper ideas of blackness.

These often come in the form of autobiographical tracks that explore Kendrick’s point of view, such as the relaxed “dodger blue”, which explores LA street culture. “tv off” (which brings back producer Mustard’s sound palette familiar from “Not Like Us”) continues the exploration of authenticity, sacrifice and liberation central to Kendrick’s catalogue, preaching for resilience in the face of the destructive industrialisation of hip hop.

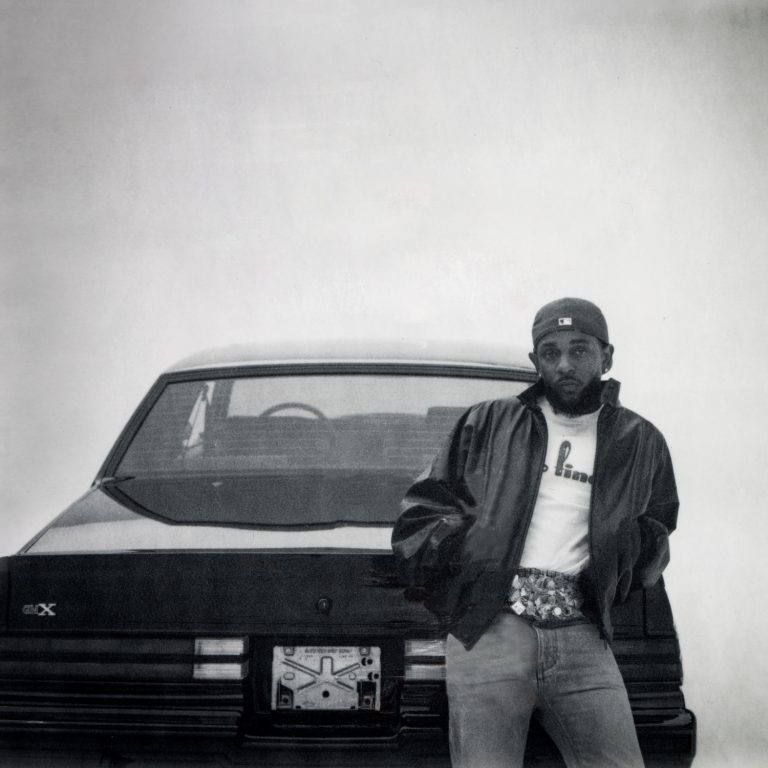

There is also the incredible “heart pt. 6”, which continues the running series of tracks usually released prior to an album’s drop. Here, Kendrick reflects on his early years in the industry, shouting out early collaborators and reconnecting with an idealistic approach to rap: vulnerability ultimately supports healing. But then tracks like “peekaboo” and “gnx” flip this perspective on its heel, providing braggadocios bangers that confront ‘fake rappers’ and hollow posers. These versions of Kendrick seem at odds, and there’s possibly some irony in calling the latter track after the muscular car depicted on the album cover.

These contradictions are central to “reincarnated”, where Kendrick narrates the struggle of black artists through the lens of John Lee Hooker and Billie Holiday. Hooker sold his songs to various commercials over the years, which Kendrick confronts in the closing lines to the first verse: “I was head of rhythm and blues / The women that fell to they feet, so many to choose / But I manipulated power as I lied to the masses / Died with my money, gluttony was too attractive, reincarnated”. There might also be a nod here to the theologians in the audience: Hooker used to wear snakeskin suits, which links to Satan’s biblical choice of snake to lie to Eve in the garden of Eden. Holliday meanwhile succumbed to drug addiction. Both, Kendrick notes, were abandoned by their fathers. In the final verse, he is interrogated by god, who calls out Kendrick’s contradictions, as the dynamic shifts further to interrogate a parallel between the rapper and Adam – or Lucifer. This imagery of the fallen angel, who captures light for power, manipulating the masses, is critical to who Kendrick is to himself, but also how fame has a corrosive quality to many black artists that evade resolving their trauma – think of Basquiat, Michael Jackson, Dinah Washington or David Stroughter. Built on a sample of 2Pac’s “Made N____z”, it also resurrects black art history without zombifying it through the use of AI (looking at you, Aubrey).

While GNX is not a concept record, it still embraces a narrative element. Multiple songs are introduced by the vocals of Mexican singer Deyra Barrera, bringing a soulful ganache to his dance floor ruminations. Throughout, Kendrick seems to interrogate a black artist’s place within his own legacy, confronting multiple of his personas, the industry, his home town and the value of destruction as a constant in art. The closer “Gloria” goes as far as to apply a name (Spanish for glory) to his muse and imagine her as a fiery, borderline toxic lover: “You were spontaneous, firecracker, plus our love is dangerous / Life of passion, laughin’ at you lose your temper, slightly crashin’ / Dumb enough to ill reaction, ain’t no disrespect / Highly sensitive, possessed, saw potential, even when it’s tragic”. In this fantasy, Kendrick confronts his own inability to live up to his ambition of mass populism as instigator (“So jealous, hate it when I hit the club to get some bitches / Wrote ’em off, rather see me hit the church and get religious”) and imagines himself wrestling with the gift of love, birthing his own evolution as an artist. If we follow the logic of “reincarnated”, then it is this creation process that, ultimately, brings undoing – but Kendrick jokes “Down bitch, I know your favourite movie, is it Notebook?” On a record filled with the hard hitting aesthetics of West Cost hip hop, it’s a moment of universal understanding – and resolution.

Even if GNX may be regarded as a “lesser” entry in Lamar’s mighty catalogue by many (if there even is such a thing as “lesser” in brilliance), it is a love letter to black culture. It never dodges a punch, never compromises. It’s both as far from the mainstream as a rap album can be, yet Kendrick’s most populist work. It’s a muscular and physical record, occasionally reserving the right to be as however banal as it wants to be, right before turning around and tearing into the culture.