Hurray For The Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra once described art and music as “a declaration of independence” for unheard and displaced citizens of Puerto Rico. Their 2017 masterpiece The Navigator was a compelling account of how personal healing and generational healing are, in fact, the same mechanism. It’s an ageless record that felt like it would have resonated in any era of popular music. It just so happened to achieve critical acclaim during the ominous infancy of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Despite the record’s arresting subject matter, Segarra’s vivid wordplay and its striking, sonorous arrangements – inspired by artists such as Willie Colon, Hector Lavoe, and Jorge Ben Jor – make you feel welcome, loved, and alive. Songs like “Nothing’s Gonna Change That Girl” and “Fourteen Floors” seem momentous, even though their deft, light-footed beauty is anchored by a palpable sadness. The music and lyrics are streamlined to hold a potent emotional current to be discharged with pinpoint precision, culminating in the thunderous outcry of “Pa’lante”. With such amazing sequencing and buildup, it’s impossible not to weep during that climax.

At age 34, Segarra’s life is a case of living to tell a ton of things. They were born in the Bronx, and their father – depicted on the cover of 2013’s Look Out Mama – is a veteran who served in Vietnam. He was forthcoming in sharing the wisdom from his traumatic experiences, which fueled Segarra’s fearless venture out on their own as a teenager. They hopped trains like the folk heroes of yonder, gaining a lot of mileage and wisdom along the way. Landing in the musical hotbed of New Orleans, Segarra “hacked the system” through punk rock and self-interrogated their place in the world through the language of folk, famously deconstructing the patriarchal toxicity of the murder ballad on “The Body Electric”.

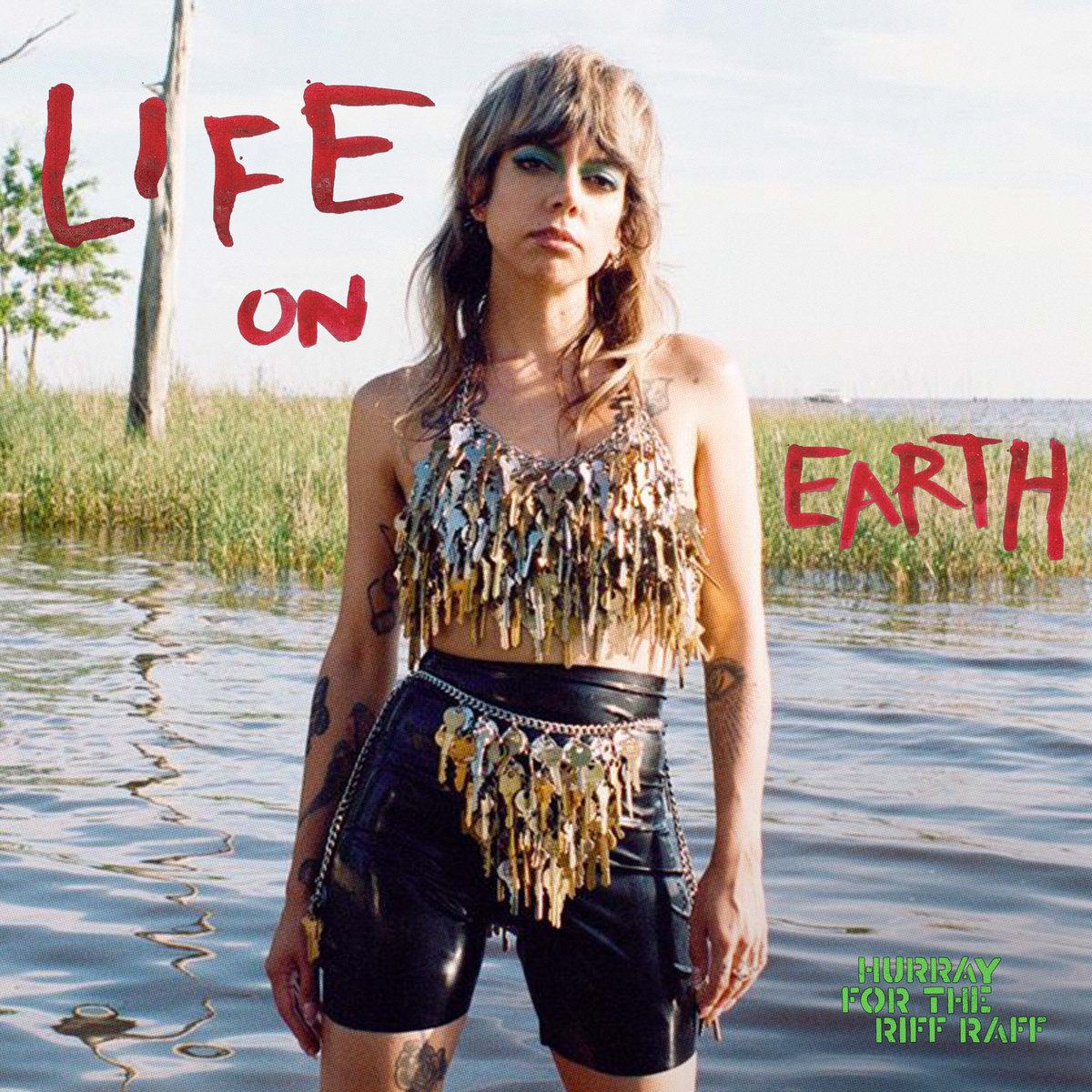

Segarra turns a blank page on their new album Life On Earth. Hurray For The Riff Raff takes more sonic risks than on any previous album, especially compared to The Navigator’s familiar musical touchstones. The rustic 60s folk, classic pop, and Latin have made way for a more disparate range of influences; Segarra mentions touchstones as diverse as fellow Puerto Rican Bad Bunny and rediscovered folk/synth pioneer Beverly Glenn Copeland. The influence of the latter seems particularly significant: Copeland once released a record called Crossin’ Over, which was about rechasing his own slave roots. He mentioned that slaves in the US made up their own Christian songs during Sunday service, which were actually coded languages on how to escape from the oppressors.

Life On Earth’s self-coined ‘nature punk’ seems to hold a similar purpose: an escape hatch from restrictive traditions to someplace unruly and unmarked. Sonically, these songs occupy a very interesting zone: partly grounded in the homespun folk and punk of Segarra’s genesis, and partly astray in horizon-peering widescreen pop. The synth-driven heartbreaker “Pierced Arrows” sits right at the epicenter, as Segarra writhes through the unrelenting change, aware that in order to propel forward, a person has to confront where they came from. And sometimes, moving on means having to transform yourself.

Though The Navigator was a balming guide through a distorted history to straddle some of the schisms created by gentrification and capitalism, Life On Earth hangs its hat on navigating the now. The songs capture the artist at an existential crossroads, unfolding like the drawing of a roadmap or the orating of a prayer. As a result, it takes a little longer for Life On Earth to land than its predecessor. Segarra has been through too many trials themself to be naïve in the soul search for a better tomorrow. In fact, they’re more inclined to magnify the harrowing reality of today, stepping out of their own comfort zone to look for fresh clues.

Adapting the syntax of hip hop, the ICE-referencing “Precious Cargo” matter-of-factly chronicles the despair of a Mexican father attempting to swim across the river – with his kids on his shoulders – only to be detained at the US border. Going back to Crossin’ Over and also the work of street poet Gil Scott Heron: music is a potentially powerful medium to help unshackle the truth. With that same spirit, Segarra uses the song’s free-form structure to namedrop all the ICE locations in the US. An audio recording of the man is played as the song bleeds out: “At the end of the day, I just want to keep helping people.”

On Life On Earth, marginalized voices are amplified and given credence. Segarra is the kind of potent lyricist who can flesh out characters and scenes with just one or two lines, paint entire panoramic worlds within the succinct space of a song. On “Rhododendron” – the most outwardly punk rock sounding track on the record – they dart their way through “police barricades” and “naked boys”, unable to look back, determined into whatever burning buildings they find.

Perhaps, Segarra doesn’t run with the same tunnel vision they might have harbored when they ran away from home before. On Life On Earth, they let the listener fully emerge in the wonder of the journey itself, dipping into more exotic textures, like on the deft, reggaeton-inflected “Jupiter’s Dance”. “Saga” – with its inviting tactile melodies and wooden percussive flourishes – describes an abusive relationship in unsettling detail, but Segarra also remarks how it was a way to cope with a “terrible news week”. They don’t resign to the inherent struggle of giving a shit, as a benevolent sax flourish joins in: “I don’t want this to be the sound of my life”.

Writing about the state of the world with such unflinching honesty is hard; increasingly hard even with every global crisis so acutely visible now. Creating music that channels the accumulating nihilism, defeat, chaos, and despair oftentimes proves to be an easy outlet. Throughout Life On Earth, Hurray For The Riff Raff manages to not only shoulder the weight, but they also evoke a rare clarity and compassion for those listening in. Segarra has such an uncanny gift for writing poetry that makes itself immediately understood.

On the plaintive piano-driven title track they wistfully recognize “the man in the mask at the desk with a flask” and “the girl in a cage with the moon in her eye”. Segarra, ever the restless vagabond, keeps running for their life, torch firmly in hand. On the sweeping “Pointed At The Sun”, they bellow: “I go out walking after twilight / Talking to the memories of all I’ve ever known”.