Drive-By Truckers’ 2004 release The Dirty South blended political commentary and historical fiction, frequently referencing the now-mythologized 1977 plane crash that resulted in the death of several members of Lynyrd Skynyrd. Throughout the album, DBT shape an epic lens on American politics and social hierarchy, spotlighting the legacy of Civil Rights legislation, the polarizing presence of Alabaman governor George Wallace, and the mid-60s electoral realignment of conservatives and Christians. Musically, the tracks drew from, synthesized, and ultimately transcended DBT’s two primary influences: the guitar-led blues-rock of abovementioned Lynyrd Skynyrd and the grunge-y prototypes of Neil Young & Crazy Horse.

Recent work, including The Unraveling and The New OK, both released in 2020, emerged from the divisions intrinsic to a post-Trumpian US. Throughout these sequences, the band adopted an expanded discourse on the contemporary landscape, offering insights into the US’s perennial challenges, including matters of race, gender, sexuality, individual rights, faith, and patriotism. As the band have evolved in terms of subject matter, so has their audial repertoire. While still making maximal use of a blues-and-distorted-rock template, replete with adrenalized chording and trebly solos, DBT’s sound has grown increasingly textural, atmospheric, and ambient.

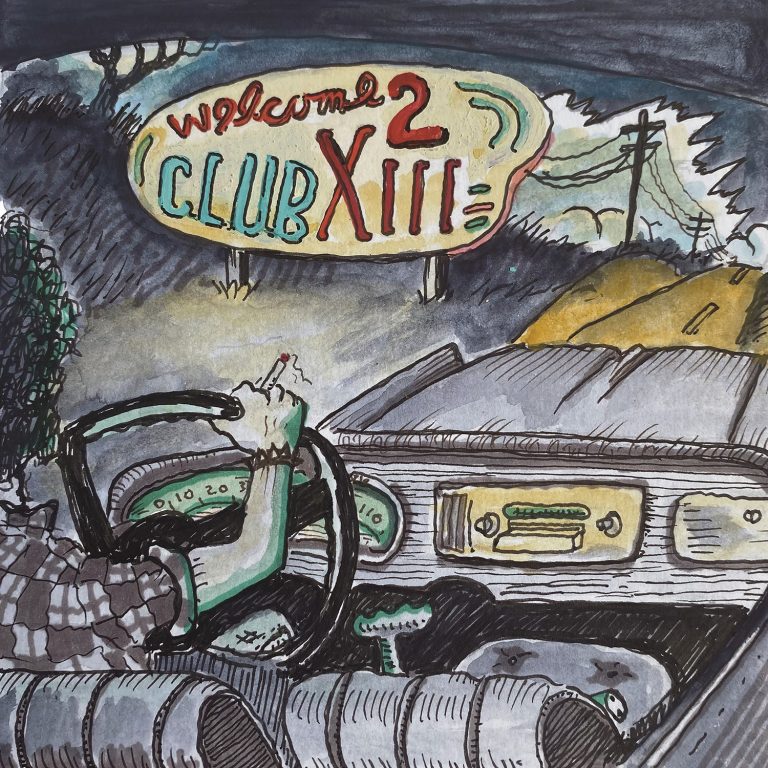

With their 14th album, Welcome 2 Club XIII, DBT step away from their critiques of the nation at large, returning, albeit as older and wiser artists and human beings, to a meta-autobiographical approach à la 2003’s Decoration Day. Overall, the album occurs as less incendiary than previous work (with the exception of the opening track), DBT at least temporarily setting aside their polemical blowtorches, instead mindfully venturing into vivid inventories of their own lives, choices, and karmic trajectories.

The album launches with “The Driver”, Patterson Hood forging a drawly sprechstimme undergirded by a galvanic guitar riff. Dream-like, the song brims with images of “a flaming dumpster,” “Klansmen,” and a car going “airborne into the trees.” Crafting a southern-goth take on Kerouac and possibly Nicolas Winding Refn’s film adaptation of James Sallis’s novel Drive, Hood employs the motif of the highway to metaphorize his and his friends’ emergence from childhood into adult life: “In a van full of stink we set out upon the plains / to the Black Hills and Rockies and Cascades / we had never been out west at least not further out than Texas / our lives spread out before us like a page.” At the end of the song, Hood introduces the notion of alternate realities, considering how key events in his life could have unfolded – and, in multiverse terms, did – in a different and less auspicious way.

With “We will never wake you in the morning,” Mike Cooley narrates the story of an inveterate addict, his voice initially accompanied by a metronomic drum beat and bass-y rumble. As the song unfolds, piano notes intermingle with a ringing and reverb-y guitar, the ambient swirl wrapping around Cooley’s gravelly voice. The title song is an upbeat and tongue-in-cheek depiction of a roadhouse populated by quirky characters. The all-too-familiar scene can also, however, be regarded as a Sartrean analogue for the afterlife, a cliché-ridden weigh station where, from decade to decade, nothing changes.

Crunchy guitars chug along infectiously on “Forged in Hell and Heaven Sent”, Cooley’s reflection on his adolescent days. Built around a lilting melody, the tune is punctuated by an instrumental segment – buoyantly rhythmic and loosely melodic guitar interplays – reminiscent of the Grateful Dead. Margo Price’s back-up vocal is aptly casual, complementing the song’s spontaneous and wistful feel. “Billy Ringo in the Dark” catalogs the doubts and a sense of existential anticlimax to which many people will undoubtedly relate: “Life came down upon you with the weight of fallen worlds / the sound of screaming dogs in the silence fetal curled”.

Closer “Wilder Days”, featuring memorable supporting vocals from Schaefer Llana, shows Hood nostalgically recalling the impulsiveness and bacchanalia of his own youth. An ethereal atmosphere frames his engaging melody, the song’s instrumentation minimal yet sultry.

Club XIII perhaps marks the end of an era, for DBT and the broader culture, suggesting that our outward-moving attention, while politically and socially significant, has to yield at some point to self-assessment. We have to face the realities of our choices and mortality, balancing ambition and activism with acceptance and introspection. Encountering our inherent silence can bring meaning to our lives. When we habituate and systematize our distractions, however, through news feeds, social media, self-aggrandizing pursuits, and other addictive orientations, we can become depressed, disconnected from ourselves and the people we love.